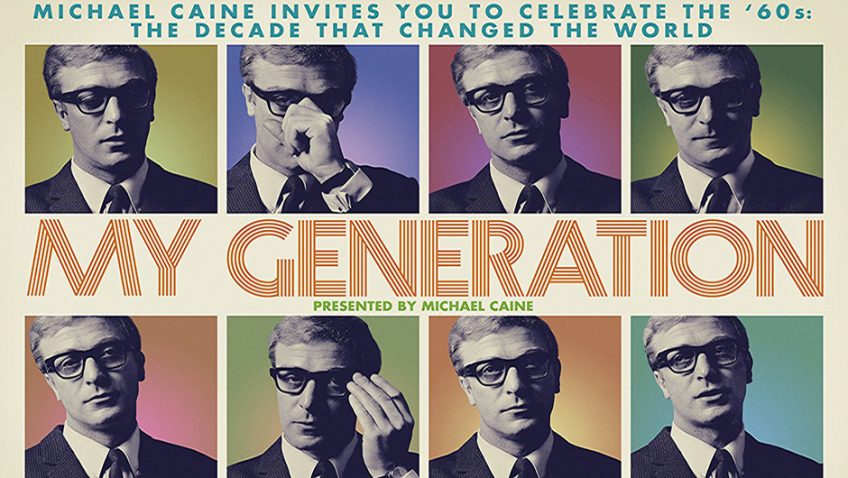

Joyce Glasser reviews My Generation (March 14, 2018) Cert 12A, 85 min.

Event Cinema – in cinemas, one day only, Tuesday March 14, 2018.

In My Generation director David Batty and Michael Caine’s contemporaries, writers Dick Clement and Ian Le Frenais (The Commitments (1991), The Bank Job (2008) and Flushed Away (2006) ensure that the personal view promised by in the title, remains centre stage. And narrator Michael Caine, a working class lad, has a grand time showing us how his generation and class appropriated the 1960s and transformed stuffy, conservative culture of post-war Britain into the hippest place on earth.

We could all imagine that 83-year-old Michael Caine has quite a rolodex. Caine, an affable narrator, mentions quite a few of the celebrity pals in his rolodex but, disappointingly, there are precious few on camera interviews let alone revelatory off camera interviews with his surviving pals. We do see some terrific footage of the 1960s; hear fantastic music from the Kinks, The Beatles and The Rolling Stones that will have you thumping your feet and we benefit from some personal revelations and Caine’s take on the class revolution that he sees as the most significant driver of the ‘60s.

But much of the footage as well as the (primarily off-camera) interviews (Twiggy on her bike; Vidal Sassoon giving Mary Quant – and everyone else – a hair cut; and everything to do with the Beatles and Stones) feel déjà vu and impersonal. What we expect from a film entitled, My Generation is some insight or thought-provoking analysis as to what, apart from the effect of the working class, made his generation’s coming-of-age so unique. There is very little about the heritage of the 1960s at the end of the third section that briefly covers the decline of the swinging sixties and even less on international influences or comparisons with what was happening in other countries.

An exception is a brief quote from Roger Daltry recalling the first time he saw Elvis Presley: ‘For the first time in my life, I saw someone who was free.’ While freedom is another hallmark of the 1960s for Caine, there is no mention of racial freedom or of influence of non-white youth. By contrast, the civil rights movement, and the liberating effect of the Beatles among black audiences is highlighted in Ron Howard’s superb documentary The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years.

But when Caine is talking about the emergence of the swinging sixties and its domination of a culture of youth, you will be having too much fun to mind the film’s shortcomings. The best part of My Generation is Caine’s anecdotes and you just wish there were more of them.

He starts, appropriately enough, with his name. Maurice Micklewhite is not a name that rolls off the tongue and young Maurice wanted to be an actor. He adopted the stage name of Michael Scott when he began acting on the stage in Sussex. But there was already a Michael Scott in London’s theatre world when Caine arrived to make his name. Caine called his agent to learn that news and had minutes to find a new name. His phone box happened to be opposite the Odeon Cinema where the 1954 film, The Caine Mutiny was playing. As Humphrey Bogart was Caine’s favourite actor, he proposed the name Michael Caine to his agent, and it stuck.

In keeping with his thesis that the 1960s was a working class revolution he attributes his break in acting to an American director, Cy Endfield, who couldn’t tell a Liverpool or Cockney accent from the then-Queen Mother’s. In another wonderful anecdote Caine explains that had Endfield been British, he never would have landed his role as an upper-class British military officer in the film Zulu.

But if Caine’s emphasis on freedom of expression – with colours, designs and styles, not to mention cinema – that transformed a dreary, gray Britain – is spot on, Caine’s insistence on class is less convincing. Marianne Faithfull, one of major ‘it girls’ of the swinging sixties and in this documentary, was born in Hampstead, the daughter of an Austro-Hungarian noblewoman, and Brian Epstein, the Beatles’ first manager, was the son of a Jewish immigrant who became a wealthy entrepreneur (owning furniture and music shops). Mick Jagger was born into a middle class family and considered being a politician while studying at the London School of Economics, before dropping out to pursue what was then his hobby.

More convincing is the series of quickly-paced montages of girls in mini-skirts, the beautiful people with their Sassoon hair-cuts and archival footage of the Stones and the Beatles (though nothing to compare with the aforementioned Ron Howard documentary). But nothing is made of the significance of Sassoon’s mini revolution when, inspired by the minimalism of the Bauhaus movement in architecture and art, he rid the nation of big hair, heavy sprays and curling irons, with a short, cropped, androgynous haircut that would make its way to Mia Farrow in 1967’s hit movie, Rosemary’s Baby.

And speaking of movies, Caine has no time for his contemporary Ken Loach who was making ground-making, influential films about poverty (Poor Cow) and homelessness (Cathy Come Home) in the 1960s, reminding us that not everybody was swinging.

At the end of the film, the tone turners darker. Caine feels that two of the major reasons for the decline of the swinging sixties were the sobering Vietnam War, a time to become politically aware; and the drug culture, as the euphoria of self-liberation through recreational drugs turned into an epidemic of self-destruction. The deaths of so many Americas (Hendrix, Joplin, Lenny Bruce) were mirrored in the overdoses of Britain Epstein, and Brian Jones (former Rolling Stones musician) and the near fatal overdose of Marianne Faithfull. The culture symbolised by its creativity was not symbolised by its decadence as it ran out of steam.

But, as an image of Caine driving in his old Aston martin from ‘The Italian Job’, suggests, it was great fun for a lot of us while it lasted.

You can watch the film trailer here: