Joyce Glasser reviews For Sama (September 13, 2019), Cert. 18, 99 min.

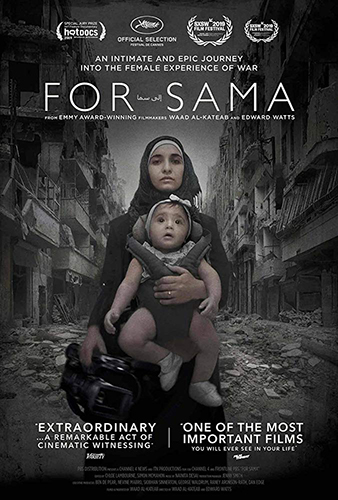

The carnage Syria has been making the news since 2011, and many heart-wrenching, important and informative documentaries have come out of it, but arguably none as powerful and memorable as For Sama. That the film exists is a miracle because the filmmaker, Waad Al-Khateab, survived in Aleppo for five years, while close to half a million people did not. What began as Al-Khateab’s optimistic student memories of the Arab Spring in 2011, shot on a mobile phone, evolved into an invaluable contemporaneous chronicle of Bashar Hafez al-Assad and Vladimir Putin’s war crimes, captured for posterity on a camera, with occasional drone shots that date stamp the Siege of Aleppo.

Waad Al-Khateab narrates the film as a love letter to her adorable daughter, Sama (now 3) who grew up in her father’s hospital in Aleppo where she was born – and not because she was ill. On 29 January 2013, long before Sama, Waad travels to the river where her footage confirms the reports. Civilians showing evidence of torture are, before our eyes, being pulled from the river, while others lie on the banks, hand-cuffed with bullets to the head. ‘Al-Assad has killed his own people.’

Waad Al-Khateab narrates the film as a love letter to her adorable daughter, Sama (now 3) who grew up in her father’s hospital in Aleppo where she was born – and not because she was ill. On 29 January 2013, long before Sama, Waad travels to the river where her footage confirms the reports. Civilians showing evidence of torture are, before our eyes, being pulled from the river, while others lie on the banks, hand-cuffed with bullets to the head. ‘Al-Assad has killed his own people.’

When the Arab Spring turned into a winter of discontent, Waad Al-Khateab, an 18-year-old economics student at the University of Aleppo, defied her parents and decided to remain in the city as a revolutionary. By then she had fallen in love with a medical student and fellow protester, Hamza. Hamza, who was engaged, was too committed to the protest, and perhaps already to Waad, to bow to his fiancée’s ultimatum, and he remained. The joyful wedding is captured recorded and for just one night, the happy couple and their friends could enjoy a semblance of normality.

Most newly graduated doctors have enough stress in their lives with a few trying patients a day. Hamza set up and ran a hospital with thousands of emergency patients, acute shortages and a volunteer staff. We see Omar, who had just won a scholarship to study Architecture at Aleppo, and Gath, a medical student, who volunteer to be nurses. Both are killed shortly after, Gath by a Russian airstrike. ‘Losing them made it even more important to go on.’

By a miracle, Hamza and Waad are away when the hospital is destroyed by a bomb, killing over 50 patients, visitors and staff. With no time to mourn, Hamza located another that would be harder for the Russians to target.

What distinguishes Waad’s film from so many other poignant and devastating documentaries is Waad’s personalised first person narration about living as a pregnant photojournalist and new mother in this infamous war zone. She is jubilant when she and Hamza buy a house with a garden, but when the house is bombed, the three (Sama is now about seven months old) move into a crowded room in the hospital. Recreation for the children is painting the sides of bombed out buses.

What we do not see is Waad learning her craft from visiting news crews. More conspicuously absent is any mention of the extremists who infiltrated the city, in the guise of activists, allowing the regime to group everyone as ‘terrorist rebels’.

Two boys bring their brother to the hospital, but Hamza can only wrap the youth’s corpse in a blue sheet. Waad captures the brothers’ grief and the mother who carries her son away. When a female fatality is brought in Waad says: ‘I hate to admit it, ‘but I envy this mother. At least she died before she had to bury her son.’ A grief-stricken mother screams at Waad’s camera, ‘Why are you filming?’ only to relent.

The answer, that she is filming for Sama was not, at that time, the primary reason, although Waad always felt she owed her daughter an explanation and apology for bringing her into such a horrific world. This construct was created after Al-Khateab began working with British filmmaker Edward Watts and editors Chloe Lambourne and Simon McMahon (Al-Khateab now works for Channel 4). They imposed a narrative structure on the 500 hours of footage and the result is a film that jumps in time to prioritise Waad’s personal story. This is occasionally confusing as much of the film is time-lined by captions, but the result is a riveting epic in 99 minutes that leaves you awed, drained, outraged, helpless and perhaps feeling guilty.

‘There’s no vegetables or fruit,’ Waad announces before we hear that Assad’s forces, that have squeezed the residents into a corner of the city, are using chlorine gas. ‘Your dad talks to the news channels all the time, but no one stops the regime.’

Amid the horrors that have given this film its unfortunate 18 rating, there are moments that help Waad and Hamza, their best friends (a primary school teacher who keeps classes going, her husband and their three children) and hospital volunteers, to go on. A heavily pregnant woman is brought in unconscious and Hamza delivers what looks like a still born baby by C-section. We see the white body being hung upside down like a skinned rabbit and slapped, but still, no sign of life. And then a cry and little creases open to reveal eyes. The mother, too, lives.

Desperate families that try fleeing toward the regime-controlled side of Aleppo are less fortunate. They are picked off by snipers from the Syrian army that has now entered the city and are one street away from the hospital.

Earlier in the film Hamza goes to the ruins of their bombed house and waters a lone, stubborn root. Just before the UN-brokered ceasefire offers the remaining residents safe passage out, Waad takes a branch from the garden, telling us, ‘it will grow out of Aleppo.’ Hamza says that he and his skeletal team have performed 890 operations in 20 days and received 6,000 people.

It is a bitterly cold December 2016 with no heat or electricity. Desperate residents board the buses. Hamza and Waad decide to stay behind until everyone has gone. ‘They are shooting at ambulances’, Waad shouts during the chaotic cease fire exodus. Their own escape is particularly perilous as Hamza, who has appeared in international news broadcasts, is known to the authorities and they fear he will be stopped at the Russian check points. They travel under cover of night with their best friends in separate cars.

‘I thought we lost everything when we left Aleppo,’ Waad, pregnant with another daughter, says. ‘But we have Sama now, and I have my footage.’ That footage is arguably the most powerful indictment of Syrian war crimes that the world has seen.

You can watch the film trailer here: