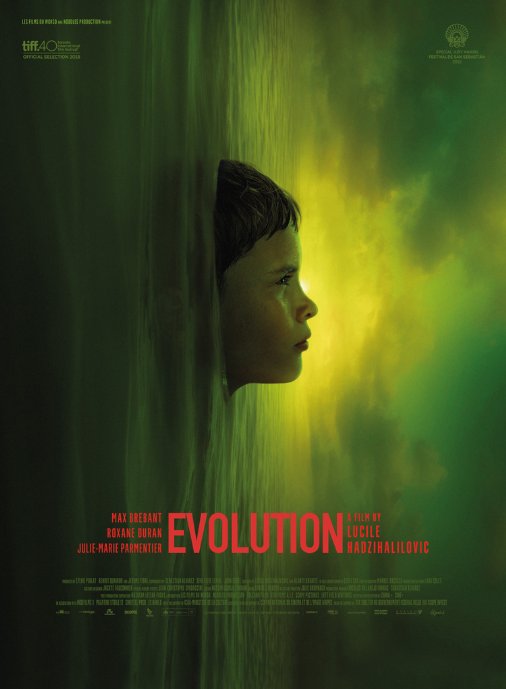

Joyce Glasser reviews Evolution (May 6, 2016)

If you happened to see Lucile Emina Hadžihalilović’s debut feature film, Innocence (2004), with its cryptic, often exasperating story and its gorgeous sinister images, you might be prepared for Evolution, the 54-year-old French actress and filmmaker’s second feature film. In between directing her own films, Hadžihalilović collaborates with her husband, the Director Gaspar Noé in postproduction and the running of their production company. While Noé is famous for the explicit sexual content of his adult films, Hadžihalilović’s two films have focused on the point of puberty and, in Evolution, a film cast with women under 50 and young boys, there isn’t an adult male in sight.

Innocence is set in a remote gothic girls’ school surrounded by a massive woodland where the new students arrive in coffins. It is either a paradise, a very protective and limited-curriculum boarding school or a place where girls are being groomed for the men who watch their dance performances. And when the girls reach puberty, they are taken away in an underground train to the real world, their first glimpse of boys and towns, and an unknown future.

Innocence is set in a remote gothic girls’ school surrounded by a massive woodland where the new students arrive in coffins. It is either a paradise, a very protective and limited-curriculum boarding school or a place where girls are being groomed for the men who watch their dance performances. And when the girls reach puberty, they are taken away in an underground train to the real world, their first glimpse of boys and towns, and an unknown future.

Evolution is also set in a remote location, a volcanic island that contains nothing but sparsely furnished white cube houses and a derelict factory transformed into a hospital. If the boarding school in Innocence offered just two subjects, school of any kind is notably absent in Evolution.

Evolution also begins with an image of death: here, the coffin is the sea, and 10-year-old Nicolas (Max Brebant) spots a drown boy with a red star fish on his chest pinned to the bottom of it. He runs home to tell his mother who hardly reacts, and scolds Nicolas for swimming alone along the rocky, rough coast. When she goes out with Nicolas to investigate, the boy has disappeared.

There are no girls in Evolution, just women and a skinny, pale 10-year-old boy living with each of them. Nicolas’ mother (Julie-Marie Parmentier) feeds him a bowl of what looks like stewed worms that she has prepared in their basic, Spartan kitchen where we never see him enjoying fruit and vegetables. The only break from this boring existence is a collective outing on the sea coast where Nicolas swims. But instead of playing on the rocky beach with the other boys, he sketches everyday objects, a starfish, for example.

Nicolas’ is also distinguished from the other boys by his inquisitive mind. He notices that his mother disappears every night and one night he follows her to the sea where he witnesses a repulsive kind of orgy of the naked ‘mothers’, twisting around and rubbing against one another, immersed in some kind of liquid.

The next event in Nicolas’ life is a trip to the hospital, a run-down former factory that is disproportionate in size to the number of inhabitants on the island. Nicolas has been told that he is sick, which is why he has to take medication, and so this trip to the hospital might be a normal consequence of his illness. But as Nicolas and his mother approach, we see another boy and his mother (also dressed in a beige tunic with her hair pulled back from her pale face) returning from the hospital. And inside the hospital he finds several of his friends.

It is around this time that Nicolas begins to doubt that his mother really is his mother. He draws in his sketchbook a woman with wild red hair, a drawing noticed by the only kind hospital nurse, (Roxane Duran), who resembles the woman in his sketchbook.

As Nicolas reaches puberty, he is confined to the hospital where the kind nurse encourages the medicated Nicolas to draw. When one of the boys dies, Nicolas tries, against all odds, to escape.

The boys have been conditioned through time and bred to be passive, perhaps weakened by their insufficient diet. We do not know why Nicolas alone seems to rise above the rest of the boys as a leader, or where the fathers are – although there may are probably not fathers in the traditional sense of the word. You wonder, too, why no outsider has noticed this strange island and investigated. It must belong to some mainland country. Or perhaps we are living in a dystopian world: non-futuristic Sci-Fi movie. As for whether Nicolas is correct in suspecting that his mother is not his real mother, Hadžihalilović, who co-wrote the script, offers up a nice homophone, as the French word for mother, ‘mère’, sounds like the word for the sea ‘mer’. And the sea, which is associated with death, also proves to be a life giving force.

For all the similarities, Evolution is more of a thriller, and therefore far more engrossing than Innocence, partly due to the sinister village, the grim medical experiments, our desire to help Nicolas escape, and the setting that resembles a painting by Giorgio de Chirico. In some ways, Evolution is a thriller and a variation of a Zombie movie as the mothers are all the same, hardly speak and seem programmed like machines with no feeling and no free will. The atmosphere is, if anything, even more pronounced and foreboding than in Innocence, confirming Hadžihalilović’s place as a master of haunting imagery, if not yet of character and storytelling.

You can watch the film trailer for here: