Joyce Glasser reviews An American in Paris: The Musical – Event Cinema, (May 16, 2018) Cert. (PG), 155 min.

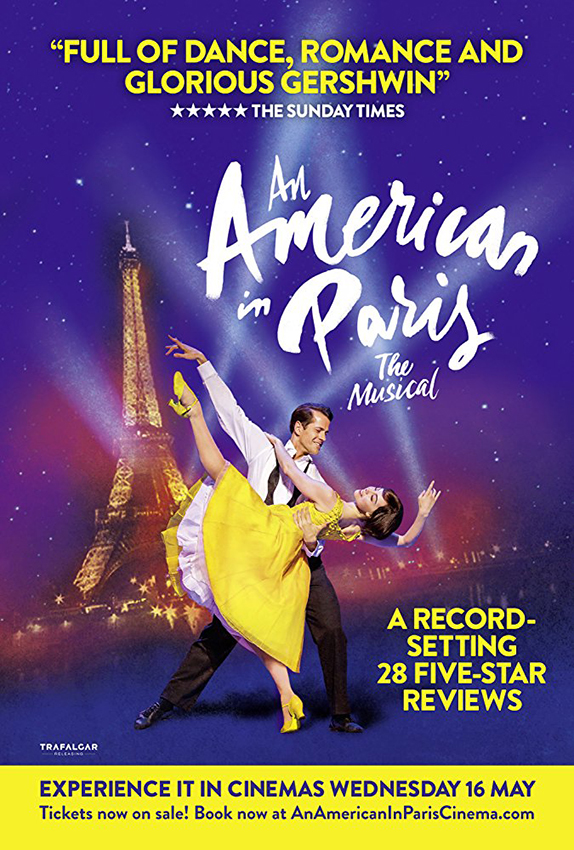

If you like musicals with a lot of balletic dancing, jazz, the Gershwin Brothers and are nostalgic for a Paris that is fast disappearing, then prepare to be entertained on Wednesday 16th May at your local cinema. Choreographer/director Christopher Wheeldon’s An American in Paris recently ended its run at London’s Dominion Theatre, but if you missed it or want to see it again, you’re in luck. A live performance with the original cast was taped for cinema release. Wheeldon’s take on Vincente Minnelli’s 1951 film is not always an improvement, but for the most part it’s like two hours of eating frosting on a cake.

Craig Lucas, who revised the script (originally written by Alan Jay Lerner), has fleshed out the story and he and Wheeldon have added a bitter-sweet gloss to the post-war Paris setting. GI Jerry Mulligan (Robert Fairchild) decides to remain in Paris to be a painter when he comes to the aide of Lise Dassin (Leanne Cope) in the chaotic Paris streets and decides he wants to remain and be a painter. Wandering through the streets, Jerry sees a woman hauled away (a possible collaborator) and women reunited – or not – with their husbands, back from the front.

Craig Lucas, who revised the script (originally written by Alan Jay Lerner), has fleshed out the story and he and Wheeldon have added a bitter-sweet gloss to the post-war Paris setting. GI Jerry Mulligan (Robert Fairchild) decides to remain in Paris to be a painter when he comes to the aide of Lise Dassin (Leanne Cope) in the chaotic Paris streets and decides he wants to remain and be a painter. Wandering through the streets, Jerry sees a woman hauled away (a possible collaborator) and women reunited – or not – with their husbands, back from the front.

Wheeldon has also given the film a more feminist touch. If Leslie Caron was the real thing – an innocent 18-year-old French dancer – she was 21 years younger than choreographer Gene Kelly’s Jerry Mulligan. American import Robert Fairchild is 30 to Royal Ballet star Leanne Cope’s 35.

If her diminutive size and dark hair cut in a bob, reminds you of Caron, her dancing has benefitted from the years of experience. Wheeldon, taking advantage of her size, seldom lets Cope’s feet touch the ground. And she is so graceful when being lifted, spun around and passed around in the arms of male dancers that her movements look effortless. Unfortunately, the close ups on Fairchild reveal sweat dripping from his body which is slightly off-putting in the romantic scenes.

If there is a lack of chemistry between Cope and Fairchild when they act, when they dance – in particular, when Fairchild’s Jerry, infiltrates the big ballet number at the end as Lise’s dream partner – they look like they were made for one another.

In this dance-heavy show, dance talent comes before voice talent, and while Cope does not ruin the pleasure of ‘The Man I Love’ she does not really do it justice. Fairchild also gets by. Zoe Rainey as Milo Davenport does very little dancing, but belts out her songs nicely and the Baurel parents do not sing at all.

If the musical is 42 minutes longer than the 1951 film, it is not just because of the dancing. Lucas not only darkens the film by its first street scenes, but with a plot that sees Lise as a Jew smuggled to England and hidden by the Baurels. Now Madame Baurel (Jane Asher), who is so conditioned to assuming a false role to avoid detection by the Vichy Government that she forgets who she really is and has become a dramatic obstacle. Her son, Henri (Haydn Oakley) was a member of the French resistance, although you’d never guess it, particularly when he is around Lise. Henri does not want to go into the family business, and hides from his family his true ambitions to go to America with a Radio City type extravaganza. Madame Baurel expects Henri to marry Lise (whose parents are presumed dead) and Lise, out of gratitude more than out of love, accepts Henri’s botched proposal.

Robert Fairchild, Zoe Rainey, Alyn Hawke, Zoe Arshamian, Sarah Bakker, James Barton, Chrissy Brooke, Jonathan Caguioa, Katie Deacon and Nicky Henshall in An American in Paris: The Musical

If Henri were also a love rival to Jerry for Lise’s affections, Lucas introduces another disappointed lover, the composer Adam Hochberg (David Seadon-Young) who is, like Lise, a Jew. A former-GI, he drowns out his sorrows at the piano in a friend’s café, convinced that there is no place for him the States or in a woman’s heart with his wooden leg. While his love for Lise is unspoken, he puts it all into the music for a ballet that she will perform to sets designed by none other than Jerry. This is the handiwork of the intentionally stereotyped American philanthropist Milo Davenport whose money is giving the struggling post-war ballet company a new lease on life.

So now Jerry, Henri and Adam, all friends with a comfortable on-stage rapport, are rivals (in the film, Adam is shocked to discover Jerry and Adam are in love with the same woman). Lise, ignorant of Adam’s romantic interest, is torn between her duty to Henri and her love for the fun-loving, seductively dangerous Jerry who is nobly adamant that Milo’s money will not buy his love.

There are a couple of problems with the script, particularly in 2018. First of all, there is not just ‘an American in Paris’, but two Americans in Paris (three if you ignore Milo). Adam in fact, is more entrenched in the Parisian way of life than is Jerry when they first meet. He has a job, knows how things work and has French friends.

And if Lise were hidden in the Baurels’ house like Anne Frank for the past four years, how can she be in a ballet company and, without practice, so superior to the other girls that she is chosen for Milo’s big ballet? It is also curious that the Baurels are in the fabric industry which was, particularly in America, associated with Jewish families. If this is the connection between Lise and the Baurels it is not clarified.

And then there is the big ballet at the end (Gene Kelly’s famous 17-minute dance fantasy boasted costumes from French painters like Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir, Utrillo, Dufy, and Rousseau). Milo declares early on that that the ballet will celebrate the connection between the Americans and the French, but Wheeldon’s final ballet, while vibrantly choreographed, suggests nothing of Milo’s brief, or it’s lost on me.

And someone appears to have forgotten that Jerry is a painter. We see him doing some sketches, but we never see him painting or going to museums. He is so effervescent, it’s hard to imagine him standing behind a canvas for hours. Perhaps it is for the best as his set designs are pretty awful. At least they recognise the role of abstract expressionism at the time. For it is New York that was emerging as the art capital of the world when Jerry makes his decision to stay in Paris to paint.

You can watch the film trailer here: