Joyce Glasser reviews Author: The JT LeRoy Story (July 29, 2016)

Jeremiah Terminator Leroy credits Dr. Terrence Owens, a therapist at the McAuley Adolescent Unit of St. Mary’s Medical Center in San Francisco, for encouraging him to write stories, which were published from 1996. So a spirited woman named Laura Albert tells us in the amusing and fascinating documentary. Author: The JT LeRoy Story.

JT is a soft-spoken, attractive, androgynous drug-addict and child prostitute. He suffered from child abuse and wrote about his life about in a style reminiscent of Jean Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers. When his first, autobiographical, novel, Sarah, appeared in 1998, the elusive JT became a media sensation. In 2004, Italian actress Asia Argento (and daughter of director Dario Argento) turned JT’s second book – a collection of stories — into a film. Everyone, from celebrities like Tom Waits, Bono and Winona Ryder, to publishers and journalists, queued up to meet the cool JT. JT was hardly obliging, however, preferring to guard his privacy.

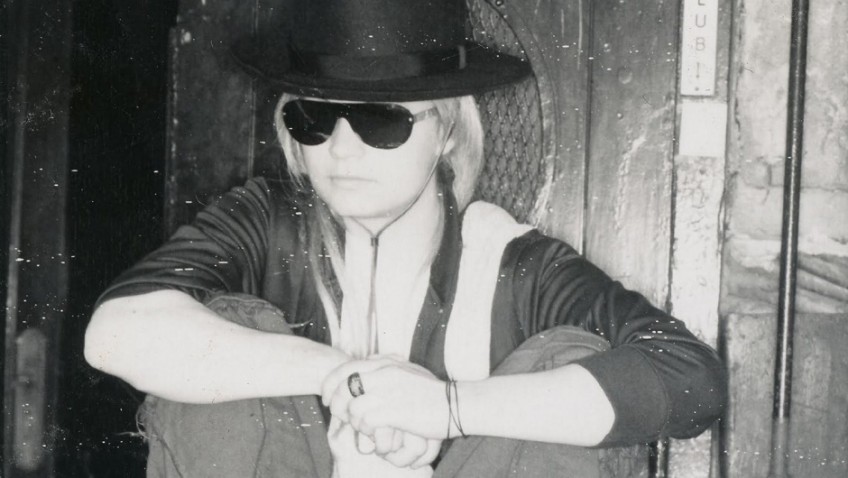

At the Cannes Film Festival, JT who rarely appeared in public, spoke in a West Virginia drawl, under shades and a blond wig, and accompanied, as usual, by his manager, Speedie. The only problem was that JT Leroy existed only in the imagination of a now 50-year-old, married, punk rocker and author from Brooklyn named Laura Frank (AKA Speedie and Emily Frasier).

Director Jeff Feuerzeig punctuates Albert’s multi-layered narration, spoken to the camera with archive footage, photographs, clips and short interviews to tell the story of how she and LeRoy entered into this increasingly daring mutually- dependent relationship. It all began with Albert/TJ phoning up literary figures such as novelist Dennis Cooper, to build a support network. Albert was surprised how easy it was to be accepted. Cooper, who wrote about troubled teens and sexual fantasies, citing Arthur Rimbaud and the Marquis de Sade as amongst his influences, introduced JT to other literary figures.

Director Jeff Feuerzeig punctuates Albert’s multi-layered narration, spoken to the camera with archive footage, photographs, clips and short interviews to tell the story of how she and LeRoy entered into this increasingly daring mutually- dependent relationship. It all began with Albert/TJ phoning up literary figures such as novelist Dennis Cooper, to build a support network. Albert was surprised how easy it was to be accepted. Cooper, who wrote about troubled teens and sexual fantasies, citing Arthur Rimbaud and the Marquis de Sade as amongst his influences, introduced JT to other literary figures.

According to the fiction, after leaving his abusive, irresponsible mother, Sarah, at a young age, or rather, after being abandoned by her, JT lived hand-to-mouth as a vagrant in California. He maintained his heroin addiction by working as a prostitute, all of which is recounted in Sarah and The Heart is Deceitful Above All Things, or by befriending an older man (Harold’s End). Then, in 1998, with the publication of Sarah, he became quasi-respectable. Of course, the risky bit is that Albert not only had a pseudonym, but a flesh-and-bone body behind her alter-ego, and that had to be someone she could trust and manipulate. That person was Albert’s sister-in-law.

Albert mentions that at times it was frustrating to be the silent talent behind her persona and it certainly must have been awkward when apparently collaborating with Gus Van Sant on the Palme D’Or winning Elephant, a film based on the Columbine High School Massacre. Albert tells us that JT Leroy wrote the first draft script, but Van Sant, who rewrote much of the script, has sole writer credit. The credits cite JT Leroy as an Associate Producer, along with Diane Keaton and Producer Dany Wolf (Lawless, Karate Kid). Even without the writing credit, such associations demonstrate the credibility of Albert’s creation, not to mention the talent.

In October, 2005, the year JT’s third book was published, Stephen Beachy exposed Albert in his article in New York Magazine, putting forward the idea that JT Leroy and Speedie were personas of Laura Albert. This hypothesis was confirmed in 2006 in The New York Times. The film concludes by briefly reviewing the fall out of the discovery, which ranged from a law suit filed by the film’s producers to those who did not understand what the fuss was all about. Albert herself seems relieved that the pressure of what became a huge hoax was off.

Director Jeff Feuerzeig is carving out a niche for himself as a filmmaker who explores the fine line between mental illness and creativity. In his previous film, the 2005 Sundance Festival winner, The Devil and Daniel Johnston, he chronicled the life of a bipolar musician/songwriter which includes bizarre episodes of demonic self-possession.

As you listen to the articulate Laura Albert, you ask yourself whether Albert has a multiple personality disorder, or if she were, like Arthur Conan Doyle, an author whose successful character took over her life and was too big to kill off. Late in the film, Albert tells us that she suffered abuse from an uncle in whose care she was left as a child. It seems that she deals with this memory by expressing herself through an alter-ego.

While the film is fascinating, a part of me regrets that Feuerzeig did not explore the equally interesting issue of whether Albert was a fake or merely carrying on the tradition of many famous writers. The poet Yeats’ used various personas, or masks, and the double- Prix Goncourt winning author Romain Gary saw his second Goncourt prize presented to the non-existent Emile Ajar. Only a few people (and certainly not the Academy) knew that blacklisted Dalton Trumbo wrote Roman Holiday, the script that won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay and was credited to another author. While Albert was sued for signing the films’ contract under a false name, Albert delivered to them an original work of fiction. The debate over the discovery might not be as lurid, but it is certainly as interesting as the story that leads up to it.

Although Albert’s damages were reduced significantly by the court as Albert could not afford to pay them, in 2008 the Authors’ Guild wrote a brief asking the court to change its verdict on the grounds that the decision [breach of contract) ‘will have negative repercussions extending into the future for many authors.’