Joyce Glaser reviews Minamata (August 13, 2021) Cert 15, 115 mins.

Johnny Depp co-produces and stars in this environmental biopic, based on the autobiographical picture book by the late “father of photojournalism”, Eugene Smith (Depp), which was co-written with Smith’s then-wife, the photographer Aileen M Smith, (Minami Hinase). As a film about a man whose conscience drives him to selflessly take on a David and Goliath battle on behalf of voiceless victims, it is engrossing and worth seeing, but suffers in comparison with Todd Haynes Dark Waters. That masterwork, released in 2020, was a victim of Covid-19 and did not get the audience it so deserved.

Unlike Dark Waters, or Erin Brockovich before it, Andrew Levitas’s film, based on a script by David Kessler, fails to find the right dramatic balance between the biographical hero, the enemy pollutant (mercury) and polluter (Chisso Corporation), and the victims whose lives were cut painfully short by cerebral palsy-like symptoms. It doesn’t help that the Chisso Corporation’s polluting of the Minamata Bay began in the 1950s in Japan with the impact far less pervasive and recent than Dark Waters’ poisonous Dupont “Teflon” compound, which the world is still consuming today.

When the film opens, it is 1971 and Eugene “Gene” Smith, is in his cluttered NYC apartment/studio surrounded by prescription pills, empty bottles and untidy piles of prints showing soldiers, bombings, wildfires and impoverished children. This sketch of a heavy drinking, hard living, photographer whose career is past its peak is never improved on or expanded in the film. Even Smith’s moment of redemption is short-changed as we do not know on a personal level, just how much he needed it.

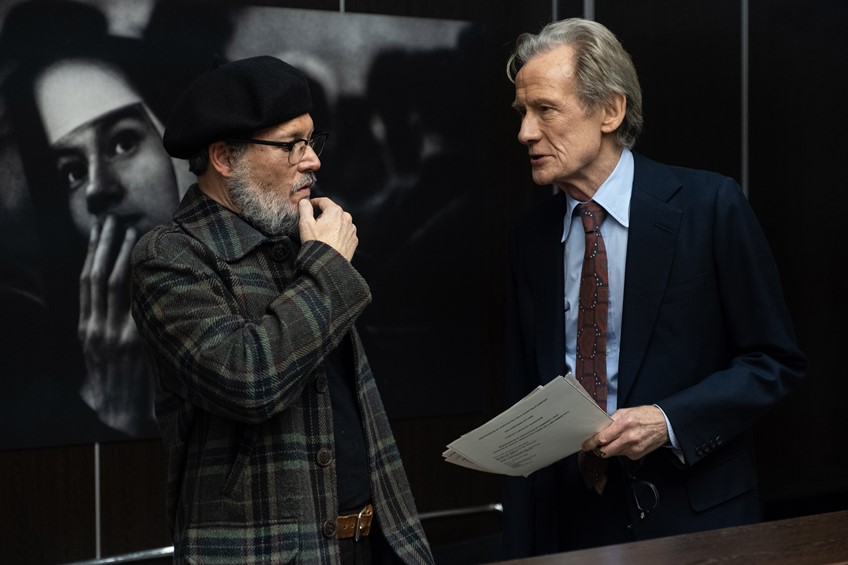

As if he owns the place, Gene storms into a layout meeting at Life Magazine, interrupting the stressed-out editor Robert Hayes (Bill Nighy). He wants Hayes to endorse his work for an upcoming retrospective exhibition, reminding him that he was the greatest photographer Life ever had. ‘You were also the most impossible’, Hayes retorts, echoing the sentiments of Newsweek (which had sacked him when he refused to use larger negatives) and Magnum Photos (which fell out with Smith over a project that ran way over budget).

We learn none of this and the film also expects us to know that Gene’s boast had merit. In 1948 he gave Life Magazine what is thought to be the first extended photo essay with Country Doctor, and from then until he left Life in 1955, the magazine thrived with his brilliant news coverage (Clement Atlee’s 1949 re-election) and photo essays including a series of photo studies of the Welsh Valleys and the miners.

Just in the nick of time is the sudden arrival of Aileen, a Japanese activist with ties to Minamata, who cons the photographer into risking his life to publicise a catastrophic industrial pollution scandal. When she shows him some photos, he returns to Hayes’ office begging Hayes to give him, and Life Magazine, a last chance.

Smith was no stranger to Japan or to risk, having been seriously wounded covering the Battle of Okinawa in WWII. Minamata was a job he could not refuse because he wanted his pictures “to carry some message against the greed, the stupidity and the intolerances that cause these wars and the breaking of many bodies.”

Upon arrival in Minamata, Smith sets out to win the locals’ trust and convince the population that the photos will name, shame and expose to the world the corruption of the Chisso Corporation which had refused to give any, and then ample compensation. Chisso had been dumping a chemical containing mercury into the Minamata Bay – which supplied contaminated fish to the whole area – over a 34-year period from the 1950s.

Smith’s hard fight for the little guy culminated in the iconic photo Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath (1971). It was right up there with Nick Ut’s harrowing photo of nine-year-old Kim Phuc running from a Napalm bomb that is credited for having helped end the Vietnam war. The shooting of this photo is the fitting climax to the film.

Smith’s career is saved by his shocking, distressing photographs that, as he promised Hayes, would redeem both himself and Life, if not save them. Life’s photo essay was to be their mutual swan song. Life ceased its regular magazines in 1972 and Smith died in 1978, partly from health problems associated with a physical assault in Minamata that nearly cost him his eye and arm.

The film ends with a series of captions that leave us feeling a bit cheated and wishing we had known all this at the start of the film. For one thing, you might have thought the romance between Eugene and Aileen in the film was dramatic licence, but actually the two apparently married in 1971 and spent their three years in Minamata as a couple.

Smith was a larger-than-life Hemingway character who was hard working, hard drinking and constantly travelling. He had enormous empathy for the suffering of the world but less so for those close to him. Women were not for life, but company for his projects like his photo essays. In the case of his Jazz Loft Project, beginning in 1957, a woman was unnecessary, and he left his partner and their four children behind to move into a loft with three male jazz musicians to embark on a major photo/recording project. His relationship with Aileen did not survive the return to NYC, and publication of their photo book. By 1954, and for the last four years of his life, cut short at 59, he had a new partner.

We learn none of this from the film (other than a brief complaint to Hayes that his kids don’t speak to him anymore) nor about Smith’s perfectionism that cost him jobs, but whose photos vindicated him. However, we learn even less about the victims (language is a problem) and about the long, complex battle against the Chisso Corporation, although as both Dark Waters and Erin Brockovich showed, these prolonged legal battles, particularly when we get to know and care about the victims, can be cinematic and dramatically involving.

With the exception of Depp, the acting, too, leaves a lot to be desired. The Chairman of Chisso and Aileen are strangely wooden, although one young victim, who is fascinated with Smith’s camera (but whose story is then dropped) is a stand-out. Depp has to be given credit for his excellent performance (he is a convincing alcoholic) and for transforming himself into the spitting image of Smith who was just a few years younger than Depp, but a lot worse for wear and tear, when the action takes place.

Joyce Glasser, Mature Times film critic.