How many people toss away a phone just because the battery’s failed or screen cracked? How many toasters and kettles hit landfill rather than being repaired and working on for years? Millions. But why is it we no longer repair and maintain appliances as we did in the past? It’s not that the repairs are so difficult: it’s because countless barriers are in place to discourage us from mending things. But already there’s a movement underway to dismantle those barriers.

In three episodes of Dare To Repair, Mark Miodownik, Professor of Materials, engineer and fixer, talks to those in the know and examines the fight for the Right to Repair and help cut this unsustainable waste. Britain, after all, is second only to Norway in the entire globe when it comes to the volume of electronic waste. Claims for recycling are totally misleading: huge amounts of water, energy and resources go into the processes, so it’s far, far more effective to repair, re-use and extend the life of appliances. There really is no Green Heaven. Recycling has to be a very last resort.

Until recently, one long-established aspect of UK culture was for parents to pass on to children a host of well-honed DIY skills, including regular maintenance and repair of household appliances. Tots to teens watched, learnt and practised changing plugs, fuses, valves and elements, replacing springs, mechanisms, nuts, bolts and washers, tightening, loosening and improvising parts, sourcing new components, and soldering wires with soldering irons heated on gas rings. The fun of working out why a vacuum cleaner, fridge, toaster, radio, TV, thermostat, Christmas light, tap, bike or car no longer worked was an exciting part of growing up, while a warm glow of pride and satisfaction was the rich reward when trial and error problem-solving paid off and gave a new lease of life to a valued item.

Repair was well worthwhile when sturdily made goods were designed to last, when spare parts, tools and user manuals were widely available at low cost and when mechanisms and technology were relatively straightforward. Yes, the goods were a lot more expensive relative to the same goods today, but repairs were not. All this changed in the age of consumerism, especially with the advent of all things electronic. In the 50s and 60s, durability, reliability and repair-ability were chief selling points: now it’s the opposite.

Today, our much flimsier goods have inbuilt obsolescence and short lifespans. While slick marketing encourages frequent, unnecessary frills and upgrades, even screws may be deliberately designed to be incompatible with regular screwdrivers. Manufacturers often invalidate warranties if owners attempt repair and refuse to share their service manuals, monopolising repairs at a high price. And what about those frustrating, sealed modules in washing machines that prevent owners replacing cheap ball bearings themselves as they used to! With spare parts hard to come by and expensive, it really is easier and cheaper to toss away broken items and buy new, especially in the UK. Poorer nations, of necessity, keep up their “fixing” skills, but once they grow affluent, like us, they repair less and pile more, instead, onto our global mountains of throwaway goods. With this consumerism crisis totally at loggerheads with a Climate Emergency that demands Zero Carbon, the Right to Repair movement has been born of common sense.

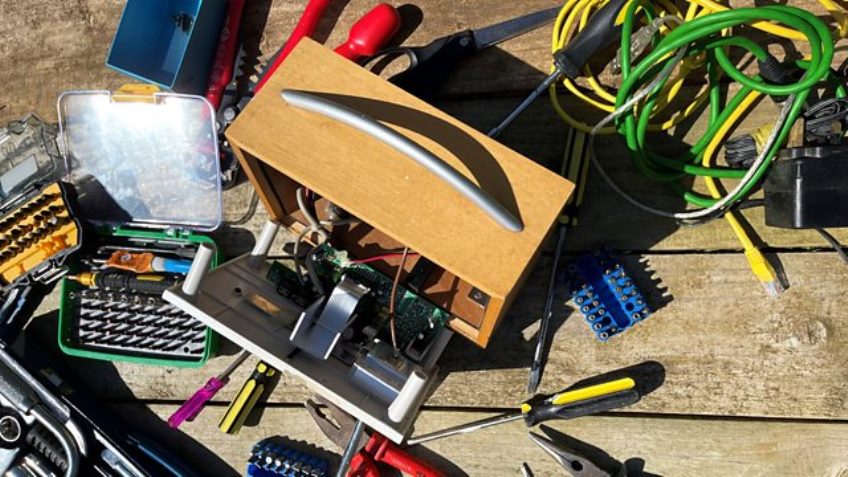

In fact, it turns out we can already carry out some of these repairs ourselves, using internet sites like I Fix It, while community repair workshops are also springing up around the country. With the right tools, spare parts, instruction manuals and web videos at hand repairs like replacing a phone battery or cracked screen can be done. The videos provide a way, too, for today’s children, our future repairers and engineers, to start picking up these invaluable skills. “Fixpert” education programmes can likewise bring back the pride and thrill of learning how things work and fixing them when they fail, combining problem solving and creativity with manual skills.

Already, in France, new goods must display how reparable an item is, while planned obsolescence is illegal. Governments and manufacturers worldwide are similarly realising, albeit slowly, that we need to legislate against unsustainable waste, ditching concepts like planned technical obsolescence and software that deliberately rejects components installed by owners. Once VAT on repairs is also reduced and spares and manuals made easily available, The Right to Repair can really take flight.

Dare To Repair explains how reclaiming the power to fix and repair could play a big part in solving the current crisis and fixing the future.

Right, tool-kits all round for Christmas, then!

Eileen Caiger Gray

Radio 4’s Dare To Repair is available long-term on BBC Sounds. To find out more click on this link.