I, Claude Monet (Event Cinema: Showing on Tuesday, 21 February 2017)

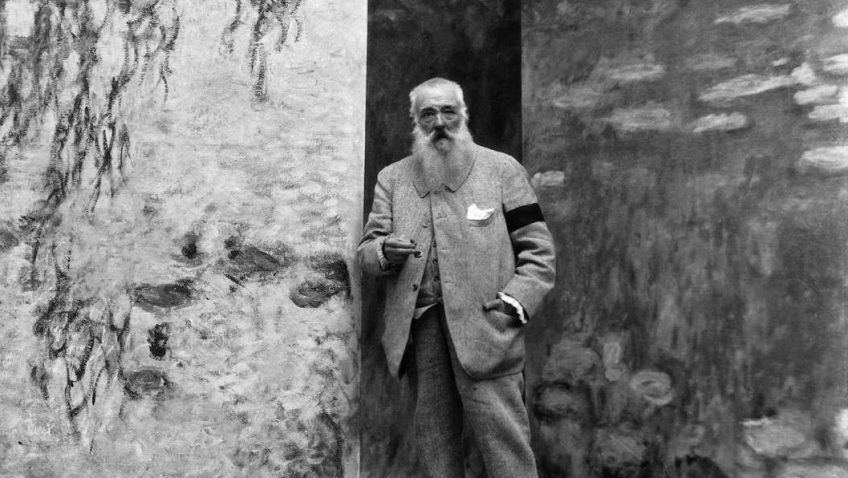

A prolific painter over the course of his long life (1840-1926), Claude Monet also managed to marry twice, support (with great difficulty) six children, cultivate the most famous garden in the world after Eden; befriend many of the painters of his day, and write some 2,500 letters. Producer/Writer/Director Phil Grabsky (who gave us the superb In Search of Mozart and In Search of Beethoven) has based this pictorial biography of Manet on a selection of these letters, read by Henry Goodman.

The film is showing as an ‘Event’ in selected cinemas: http://www.exhibitiononscreen.com/en-uk/find-a-screening on 21 February.

Born in Paris in 1840 and raised in Le Havre, Monet was perhaps destined to be a painter in the open air, an impressionist. An unruly student, he equated the four walls of a school with a prison. At the age of 17 he was making money selling caricature portraits in front of a picture frame shop. There he met the painter Boudin who took him to paint outdoors. Monet describes his first outing with Boudin as ‘the removal of a veil…I grasped what painting could be.’

It was in Honfleur, 1864, that Monet encountered the problem that was still plaguing him decades later in Rouen. In a letter to his second wife, Alice Hoschedé, dated 12 February, 1892, he complained: ‘Dear God, this cursed Cathedral is hard to do… Fourteen paintings on the go today…I’m exhausted and it seems that every day the light changes: it gets whiter and higher up.’ For in 1864, he realised, ‘When I see nature I feel I can capture everything – and then it vanishes when you’re working!’

It was in Honfleur, 1864, that Monet encountered the problem that was still plaguing him decades later in Rouen. In a letter to his second wife, Alice Hoschedé, dated 12 February, 1892, he complained: ‘Dear God, this cursed Cathedral is hard to do… Fourteen paintings on the go today…I’m exhausted and it seems that every day the light changes: it gets whiter and higher up.’ For in 1864, he realised, ‘When I see nature I feel I can capture everything – and then it vanishes when you’re working!’

Grabsky includes an extensive array of familiar and less familiar paintings to illustrate the letters. He knows how long to spend on each painting and when to linger on close-ups as in the Turner-inspired Impression Sunrise, painted at Le Havre in 1872, and believed to have given rise to the name of the movement. Grabsky supplements the artist’s impressions with portraits of Monet by his peers (including Renoir and Manet) and original footage at the spots where Monet painted.

A significant number of letters were either written to his two wives, Camille Doncieux (m 1870-1879) and Alice Hoschedé (m 1892-1911) or were about them. On May 22, 1867, living with his model and mistress Camille in a cottage in Argenteuil with their son, Jean, he writes that he is ‘happier than ever…I’m working non-stop.’ We see the charming domestic scene, The Luncheon from 1868; and Manet’s The Monet Family in the garden at Argenteuil to demonstrate the tranquility of domestic bliss. There is also a lovely photo of Jean on his ‘mechanical horse’ although we do not see the painting of that horse that remained in Monet’s possession until his death.

A beautiful portrait of Camille (Woman in a Green Dress) was accepted by the Annual Salon and he made a total 800 francs in sales. But by 1867, the money worries that were to plague him until the early 1880s were compounded by Camille’s illness (probably cancer). In a letter of January 1878, he moans, ‘In two days we must leave Argenteuil’; and in a letter dated 30 March Monet complains, ‘My wife just had another baby and I am unable to pay for medical care that mother and child must have.’ The family moved to Vétheuil as we see from The Road to Vétheuil of 1880. Monet calls it ‘a ravishing place’ and vows, ‘I shall only go to Paris (he disliked cities)…when I need to sell my paintings.’

But in a letter dated 10 March 1879 to a person whose name I could not make out, he writes: ‘For a month I have been unable to paint because I lack the colours. That’s not important. Right now it’s my wife’s life in jeopardy that terrifies me. It is unbearable to see her suffer.’ Her suffering ended on 5 September 1879 and is marked by a letter and a moving painting of whites, greys and purple, entitled Camille Monet on her Deathbed.

What we do not learn from the letters is that the family was renting space in the home of Ernest Hoschedé, a wealthy department store owner (soon to go bankrupt) and patron of the arts. Monet travelled during the 1880s as we see from paintings from Etretat and Italy, but what we do not know is that Ernest’s wife, Alice, had been caring for Monet’s two children and her own six. We do hear several letters from the 1880s in which Monet expresses his love for Alice, (whose portrait we see) and his dismay at her unhappiness, but we do not know the source of her misery (she and Ernest were still married for one thing). On 19 February 1883, Monet writes to Alice ‘I collapsed in tears. Do you mean you want to separate from me right away?. But the next time Alice is mentioned is in a letter stating that he and Alice are moving house (they eventually move to Giverny).

In a revealing letter of 9 November 1985 to Alice, he writes, ‘You say you think of savings all the time but you cannot seem to manage to,’ and he suggests it will do the children good to go without. Meanwhile, Monet leaves Alice to cope on her own while he writes to her of the incredible places he sees and of his agonizing work.

At least Alice lived to enjoy the turn in the tide. In 1886 he writes to Berthe Morisot, confirming the success of a show, ‘It’s been a long time since I’ve believed you can educate public taste.’ And in 1887, he writes to his art dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, ‘…business is going well. I’ve sold almost all my paintings.’

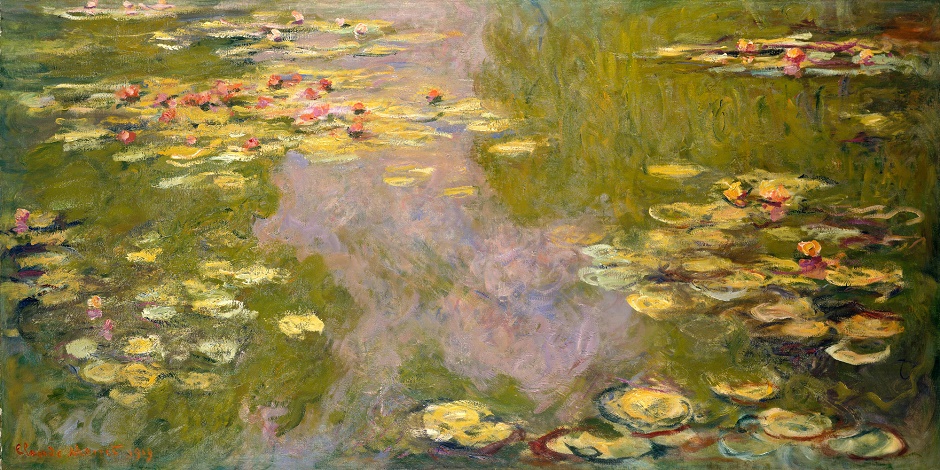

out of focus: top right

Working Title/Artist: Water LiliesDepartment: European PaintingsCulture/Period/Location: HB/TOA Date Code: Working Date: 1919

photography by mma, Digital File DT1899.tif

retouched by film and media (jnc) 12_8_10

There are also a fascinating letter to the local council about public protest over his pond at Giverny and others referring to the death of Alice in 1911, Jean in 1914, his dwindling eye-sight, the death of the last of his circle, Degas, and his refusal to move to safety in WWI: ‘If they insist on killing me, they’ll have to do it in the midst of my paintings’. The letters end with his correspondence with George Clemenceau over his gift to the nation of his water-lily panels, on which he worked until his death at 86.

The gaps in the letters and several letters whose writers and/or recipients are not identified, or are not recognizable are a problem that could have been resolved by captions. The letters are, however, well selected and provide an overview of Monet’s intimate life, concerns as a painter, his obsession with his work, and, to some extent, the kind of person he was.