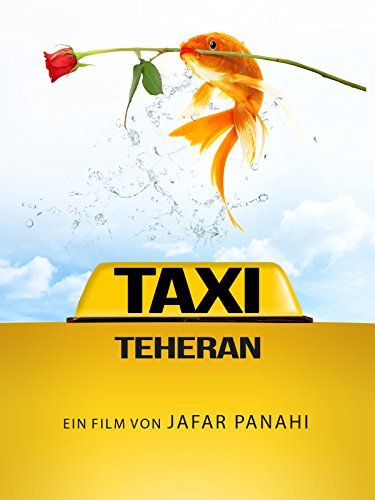

Joyce Glasser reviews Tehran Taxi (October 30, 2015)

In Tehran Taxi, as in the Royal Academy’s current exhibit of the Chinese conceptual sculptor Ai Weiwei, we witness the green shoots of creative freedom furtively pushing through the cracks in the prison walls of repression and censorship.

Iranian auteur Jafar Panahi, whose films, The White Balloon (1995) Mirror (1997), The Circle (2000) and Offside (2006) won major awards outside of his homeland, is in the fifth of a twenty-year ban from filmmaking, giving interviews or leaving the country.

And yet, with a shoestring budget, and a cast and crew who cannot be credited for fear of reprisals, Panahi has delivered a social satire and political commentary of such power that we might want to reassess our own inflated film budgets and deflated ideas.

In 2011, while awaiting his appeal (for the ban and a six-year jail sentence) Panahi made This is Not a Film, a video diary of his life under house arrest. The film was famously smuggled out of the country on a flash drive inside a birthday cake bound for the 2011 Cannes Film Festival. Closed Curtain followed and, last February Panahi won the Golden Bear for Tehran Taxi.

At first we do not see the mystery driver. The first customer is an opinionated, rather unpleasant, man who argues with the second passenger, a strong minded female teacher, about equality, Sharia Law and the execution of thieves.

The man is all for it while the teacher wants society to consider the correlation between poverty and theft. As he exits the taxi, the boorish man finally tells the curious teacher that he is a mugger by trade.

The next passenger, a stout, sweaty opportunist who runs a dodgy home movie rental business, recognises Panahi with a mix of surprise, admiration and financial interest, as Panahi has done business with him before.

The next passenger, a stout, sweaty opportunist who runs a dodgy home movie rental business, recognises Panahi with a mix of surprise, admiration and financial interest, as Panahi has done business with him before.

‘You asked me for Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, by Nuri Belge Ceylan,’ he reminds the Director, ‘and Midnight in Paris’ (Woody Allen’s Oscar winning film).

Later, when a film student asks Panahi about choosing a subject for a film, Panahi tells him that ‘you’ll know it when you see it’, an ironic reference perhaps to This is Not a Film and the one we are watching.

The relatively light tone quickly switches to drama when a man hit by a bicycle is rushed into the taxi by an hysterical woman, leaving blood stains on the light interior.

Delirious, he pleads with Panahi to record his will on his mobile phone so that his wife will get their house if he dies. Panahi refuses to accept money from the stressed couple (so far, he has never accepted money).

Filmmaking and politics merge in an explicit manner with the next group of passengers. The first, a friend of Panahi, is a human rights lawyer who leaves a rose in the car for anyone watching, as she heads to a prison to visit the family of the hunger striking prisoner Ghoncheh Ghavani.

Viewers may recall that Ghavani was the woman arrested for trying to enter a stadium to watch a men’s volleyball game. We learn that, like Panahi, the lawyer has been banned from practising her profession, a nefarious tactic to ensure that political prisoners are deprived of representation.

We are treated to some comic relief when Panahi picks up from school his lively, camera-carrying 10-year-old niece, Hana. The thrust of the conversation quickly turns ominous, however, when Hana tells her uncle about her new school project.

She is to make a short film, adhering to a set of rules that include: respect for the veil; avoid sordid realism; give characters the names of Islamic saints; no contact between men and women, and the like.

When Hana asks her uncle what sordid reality means, he answers: ‘There are realities they don’t like to be seen.’

The film is a nod in its minimalist style and its structure to Panahi’s mentor, the Iranian Director Abbas Kiarostami, now 75. In both A Taste of Cherry (1998) and Ten (2002) Kiarostami’s protagonists drive around Tehran, picking up in their car or just talking to what turns out to be a cross section of society.

Panahi, playing himself, does not tell us what is real and what is scripted in his film, so we do not know whether he is driving a taxi out of boredom or financial necessity, or merely playing a taxi driver as a device, like Kiarostami’s, to convey his message through conversations with passengers.

Whatever the case, by all accounts Panahi should not give up his day job. He never accepts any money and is criticised for stopping to ask another driver directions to a well known location. The movie rental passenger, surprised to find the great director behind the wheel, concedes, ‘It’s a job, but you are out of place in it.’

Panahi is on familiar ground however, when two fat women of a certain age enter his taxi carrying a gold fish bowl en route to a sacred spring. At one point when the taxi jolts and the bowl spills, Panahi rushes to the back seat to save the fish. Hana later finds a soggy purse in the back seat and Panahi drives to the spring to return the purse to the women.

In The White Balloon (written by Kiarostami) a young girl nags her impoverished mother for the money to buy a goldfish, only to loose it on the way to the market, until an unlikely saviour makes an appearance.

But the fairy tale ending gives way to some of that sordid realism as Panahi himself falls victim to a theft that might well be politically motivated.

You can see a trailer of the film here: