The Painted Bird (released digitally and in selected cinemas nationwide [UK & Ireland] from 11 September 2020) Cert 18, 169 mins.

Nothing will prepare you for Czech producer-writer-director Václav Marhoul’s disturbing, visually stunning and minimalistic adaptation of Polish born novelist Jerzy Kosiński’s controversial 1965 novel, The Painted Bird. Although long and episodic, the film is an intense – if hard going – visceral experience from start to finish. Marhoul wisely eschews the distraction of novelistic narration or voice-over, although the film is divided by chapter headings, indicating the names of the otherwise nameless characters the protagonist and the viewer are about to meet.

The boy (non-actor Petr Kotlár) possibly a gypsy or Jewish boy, has been left with an elderly, peasant relative (Nina Shunevych), somewhere in rural, Eastern Europe at the end of World War II. In exchange for doing arduous chores, the old woman gives him food and shelter. There is no joy in his life or love in their relationship and one day he sends a message down the river on a toy boat, “Come Fetch Me.”

For most of the film’s 169-minute running time we do not know anything about this “me” or whom he is hoping will fetch him. The boy’s name, and the fate of his parents is reserved for the end, as though the boy’s ordeal is universal.

When the old woman suddenly dies, the boy, in panic, accidentally sets the house on fire and watches it burn to the ground. Homeless, with just the shirt on his back, he sets forth on an odyssey of unspeakable horrors. We see the world through the boy’s eyes and it unsettles us because it is an inhabited world, but divested of civilisation.

In many ways, the film resembles John Hillcoat’s 2010 dystopian survival film, The Road, only here the world is imploding, but not yet post-Apocalyptic – and the boy is alone, at the mercy of uncaring adults. He wanders through a countryside ravished by Russian and German soldiers and infested with superstitious, barbaric locals doing their bidding to survive.

The boy watches as desperate men, women and children jumping from packed trains bound for concentration camps are shot in the back and their belongings are pillaged by human vultures. His face registers nothing, perhaps because nothing can shock him anymore. He encounters, and is taken in by, ignorant, cruel, sexually deviant and anti-Semitic farmers, villagers, millers, witch doctors, bird-catchers and soldiers as he witnesses – and experiences –rape, bestiality, assault and murder.

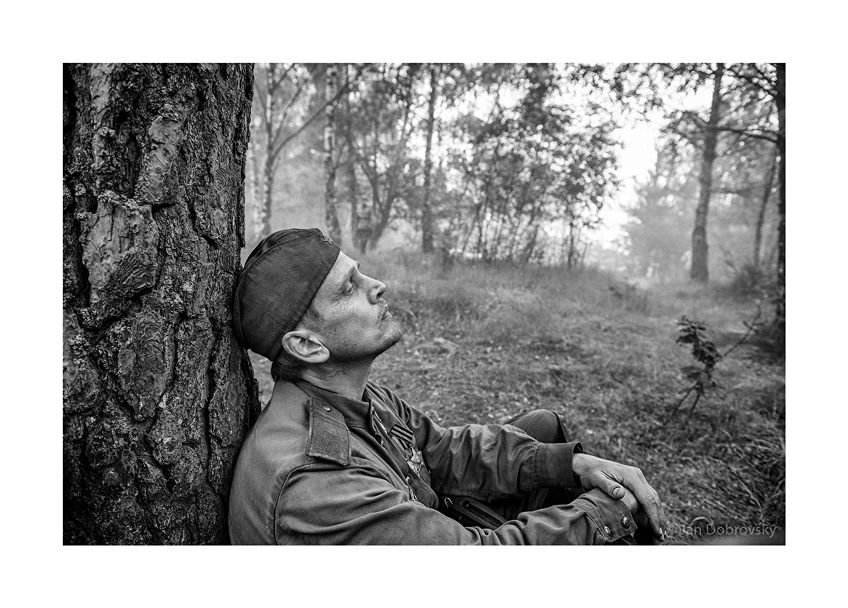

A Russian sniper (Barry Pepper, pitch-perfect) takes the boy under his wing and demonstrates the meaning of “an eye for an eye”. Though they often backfire, there are isolated acts of kindness: from a local Priest (Harvey Keitel); a German soldier (Stellan Skarsgård) and the abused wife (Michaela Doležalová) of an old miller (Udo Kier) who gouges out a the eyes of a suspected rival.

Blindness may be a blessing, given the sights that unfold in cinematographer Vladimír Smutný’s (the Academy Award winning Koyla) sumptuous, monochrome cinemascope cinematography. The choice of black and white is not only essential to convey the period setting and the colourless journey, but in its symbolic depiction of good and evil.

The novel was heralded as one of the most powerful and brilliant novels of the century, but controversy soon followed. The story was originally described by Kosiński as autobiographical, but upon its publication by Houghton Mifflin he announced that it was a purely fictional account. The anti-Polish sentiment was excused as literary licence by critics who pointed out that the work was “surreal” and did not intend to portray actual events.

The cast is a well-integrated combination of unknown actors, non-professionals, and well known American, Canadian-American, British and European actors who blend in surprisingly well in unexpected supporting roles that showcase the range of their talent.

The title derives from one chapter in which the boy empathises with a captive bird that is painted before being returned to its flock, which attacks it for being different. It is clear long before this scene, however, that the film, while reflecting the author’s childhood memories of World War II in Poland, is a fable or allegory about the difficulty of one’s retaining humanity and dignity in trying times, and the cost of being different.

The traumatised boy hardly speaks, and little registers on his face, making it difficult for us to know him. We can, however, follow his gradual loss of innocence, trust, and ability to love. In this, The Painted Bird must be one of the saddest coming-of-age films ever made. That said, a word written on the window of a train, like the clue in Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (1938), gives us hope.

You can read our review of The Road by clicking here.