Robert Tanitch reviews Long Day’s Journey Into Night at Wyndham’s Theatre, London WC2

Eugene O’Neill’s masterpiece, an act of exorcism, written in tears and blood, was so autobiographical that he didn’t want it published until 25 years after his death.

It is, perhaps, the most painful and acrimonious of all 20th century dramas.

Written with deep pity and understanding and forgiveness for his family, O’Neill didn’t want it performed at all.

His wishes were ignored. Following a premiere in Stockholm, the play was produced in New York in 1956, three years after his death, when it won a posthumous Pulitzer Prize.

The play’s great weakness – its garrulousness, its inordinate length, and its endless repetitions – is paradoxically its greatest strength.

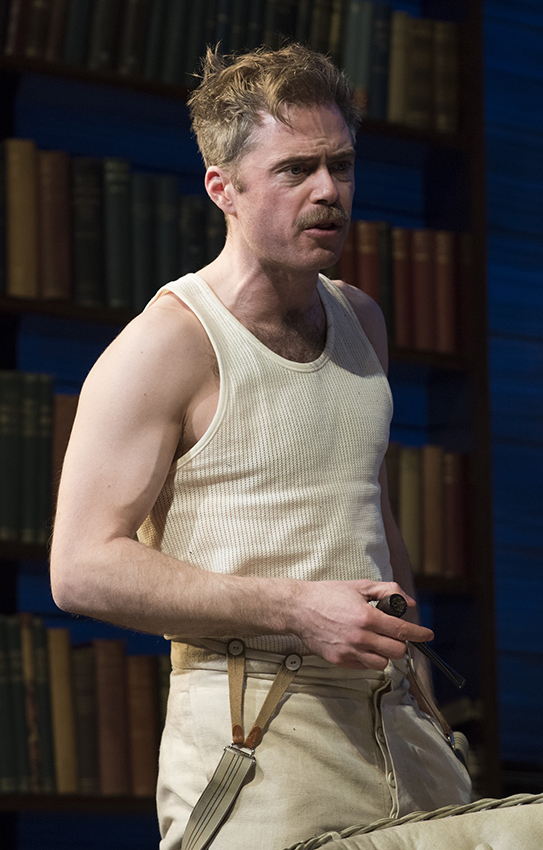

Long Day’s Journey Into Night has always attracted the finest actors and directors. The present revival is by Richard Eyre and has Jeremy Irons and Lesley Manville as James and Mary Tyrone.

Thirty-six years of marriage is concertinaed into one long day.

The Tyrone family cannot forget and they cannot forgive. It is impossible for them to do so, for the past is the present, just as the past is the future, too. In their guilt, they blame each other, for what they are: miser, morphine-addict, wastrel, and consumptive.

The bitterness is in every word they utter. The knife is turned in the same wound over and over again, an endless cycle of self-destruction.

James Tyrone (a portrait of James O’Neill, Eugene’s father, the Irish born American actor, 1846-1920) could have been a great classical actor to rank with Edwin Both. Instead he had “the good bad luck” to find a goldmine in The Count of Monte Cristo and was trapped in it for a quarter of a century, his public wanting to see him in nothing else. He played it for some 6,000 performances, mainly in one night stands up and down the country.

Tyrone is so mean he cannot bring himself to spend money on his consumptive son and send him to a decent sanatorium because he fears he will die anyway and the money will have been wasted.

His wife has been hooked on morphine, ever since a quack put her on the drug to carry her through a difficult pregnancy. She has lived out her lonely life in second class hotels, waiting for her husband to come home drunk.

Lesley Manville is superb.

Matthew Beard is also very impressive as the consumptive son (a portrait of the young Eugene O’Neill).

Rory Keenan as the eldest son has a fine drunk scene when he confesses to his brother that he has always wanted him to be a failure like himself.

Only two things are missing in Richard Eyre’s admirable taut production and that is the ramshackle house the family actually lived in and the all-enveloping fog, the physical embodiment of their isolation and loneliness.

Only two things are missing in Richard Eyre’s admirable taut production and that is the ramshackle house the family actually lived in and the all-enveloping fog, the physical embodiment of their isolation and loneliness.

To learn more about Robert Tanitch and his reviews, click here to go to his website