I saw Diana Leblanc’s production on stage at The Festival Theatre, Stratford, Ontario, Canada in the mid-1990s. This performance is a filmed version of that production. It’s great to see the actors’ faces in close-up.

Eugene O’Neill’s play is one of the pillars of American theatre, a modern, unforgettable masterpiece whose very weaknesses – the inordinate length and endless repetitions – are undoubtedly a part of its strength.

The Tyrone family cannot forget. They cannot forgive. They are continually raking up the past. In their loneliness, guilt and failure, they blame each other for what they are: a miser, a drug addict, a waster and a consumptive. The bitterness, the anger, the self pity is there in every line. There is no relief from the unrelenting recriminations. Time and time again the knife is turned in the wound.

Long Day’s Journey Into Night concentrates 35 years of marriage into one night. Strongly autobiographical, written in blood and tears, it is one of the most draining plays I know, draining on actors and audiences alike.

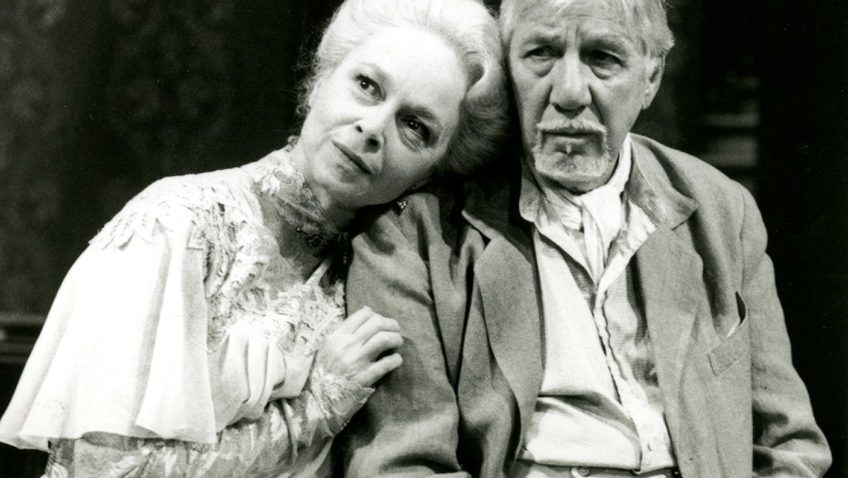

James Tyrone could have been the best actor of his generation; instead he turned matinee idol and wasted his career in The Count of Monte Cristo. William Hutt, more sympathetic than many actors in the role, gives a fine account of how his impoverished childhood taught him to be a stingy miser and led him always, even where the health of his family was concerned, to seek out second-rate bargains. The result is a wife who is morphine-¬addicted and a son who is consumptive.

Mary Tyrone, his wife, eked out her life in ugly rooms in second-rate hotels. Frail, nervous, horribly lonely, never still, constantly fussing with her hair, she drifts about the stage in a world of her own, a sad, lost figure, occasionally girlish, even skittish. Dreams of youth and the disillusionment of old age are punctuated by unexpected barbed asides at her husband’s expense. Martha Henry’s self-conscious and mannered technique is totally in keeping with the part she is playing. A wonderful performance.

There is also a fine performance by Peter Donaldson as James, filled with bitter self-hatred, who confesses to his brother that he has always been a rotten influence and deliberately so because he wanted him to be a failure just like himself. Tom McCamus as the ravaged, vulnerable, consumptive Edmund is equally impressive.

The production and the ensemble acting, totally without histrionics, was as powerful and as distressing as any I have seen. Somebody should have brought the original stage production to London!

To learn more about Robert Tanitch and his reviews, click here to go to his website