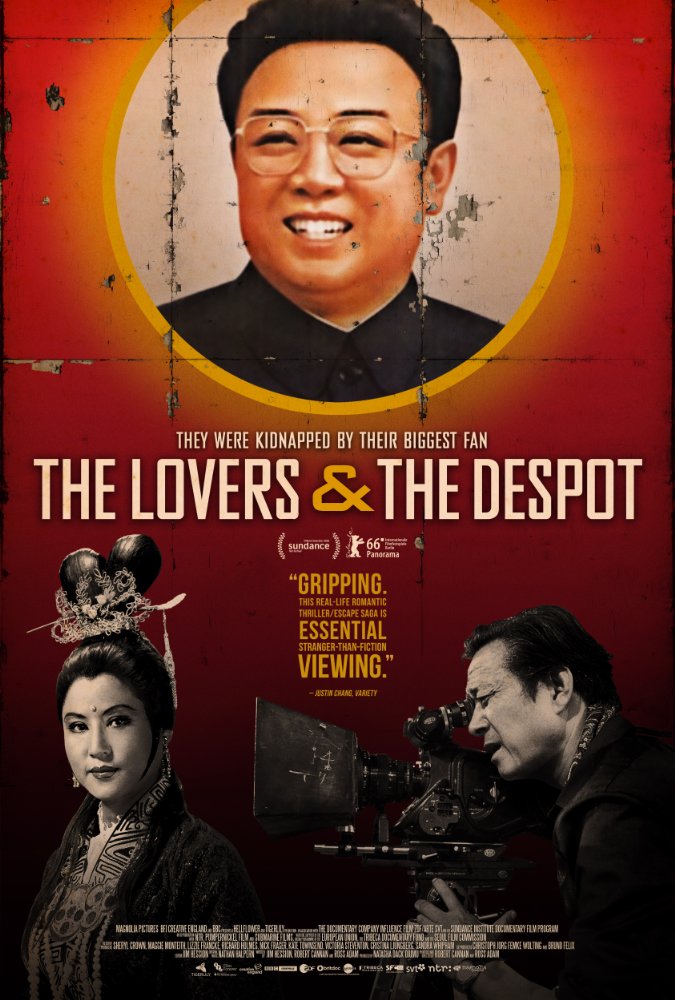

Joyce Glasser reviews The Lovers and the Despot (September 23, 2016)

If anyone tries to tell you that truth is not stranger than fiction, send them to see The Lovers and the Despot, a riveting documentary about how film buff Kim Jong-il, the late North Korean dictator, kidnapped a South Korean film star and her famous director-husband in order to kick-start the North Korean film industry. If the documentary does not do full justice to the story The Lovers and the Despot is a must-see film for cinephiles or anyone who thinks that they have seen it all.

Now 89, Choi Eun-hee, a 1950s and 1960s film star in South Korea, narrates the film recreating her remarkable life’s journey as though it were a film script. She tells us that she met the young, handsome and ambitious South Korean director Shin Sang-ok on a film set and they fell in love.

hey married, adopted two children and made films together, becoming the golden couple of South Korean cinema. This blissful scenario did not have a happy ending however, as Shin was unfaithful and fathered a child with ‘a young and inexperienced actress’. A director and obstinate producer whose vision always surpassed his budget, Shin was continually in debt and the company eventually closed.

In 1978 Choi divorces Shin and finds herself looking for work. When an invitation to attend an interview at the Golden Tripod Film Company in Hong Kong arrives, Choi packs a small bag and walks right into a North Korean trap. Choi tells us how she was bundled into a boat and endured a week-long sea journey during which she was continually drugged. When she arrives in what turns out to be North Korea, however, the delusional Kim Jong-il greets her with the words, ‘Thank you for coming!’ Although Choi lives in relative luxury and Jong-il treats her with the respect that a film buff owes to a star, she longs for her children and homeland.

In 1978 Choi divorces Shin and finds herself looking for work. When an invitation to attend an interview at the Golden Tripod Film Company in Hong Kong arrives, Choi packs a small bag and walks right into a North Korean trap. Choi tells us how she was bundled into a boat and endured a week-long sea journey during which she was continually drugged. When she arrives in what turns out to be North Korea, however, the delusional Kim Jong-il greets her with the words, ‘Thank you for coming!’ Although Choi lives in relative luxury and Jong-il treats her with the respect that a film buff owes to a star, she longs for her children and homeland.

Although the filmmakers never explain why, Shin goes off alone to Hong Kong in search of his ex-wife. Apparently Shin, too, is now kidnapped but his treatment is far more severe than Choi’s. Shin is incarcerated in a prison in solitary confinement and although he escapes, he is caught and imprisoned again. Then suddenly, after four years, he meets Kim Jong-il (who tosses off the incarceration as an unfortunate mix-up) and to his astonishment, is reunited with Choi.

The despot, who has about 20,000 film titles in his collection, makes it clear that he is relying on Shin and Choi to transform the pathetic, amateur industry North Korean industry into an international force to be reckoned with. Money is no object.

Eventually Shin and Choi, who between the two, write, produce, direct, provide crew services, and star in the films along side North Korean actors, are able to their own choose apparently introducing the first love story into the archives. And, after several years, they are allowed to attend film festivals, albeit under heavy guard.

While British directors Rob Cannan and Ross Adam include various clips from Shin’s output, we want to see more and longer clips, including Shin’s answer to Titanic. Nothing that we see convinces us that these films would be accepted in European film festivals, but it is travel to these festivals that offer the pair the means of escape.

What the film lacks in terms of clips is made up for by the revelatory private recordings that Shin and Choi made of their conversations with Jong-il. Obsequious and forever assuring the despot of their loyalty, Shin and Choi offer the world rare recordings of the man’s voice, not to mention his vacillating comments on the film industry. Or, maybe the recordings suggest that the ambitious director, ruined in his native South Korean, has made a Faustian pact with the devil incarnate and is actually enjoying his newfound fame. While we do not learn whether Choi and Shin remarried, perhaps, too, Choi is enjoying her new relationship with Shin.

Ironically, then, although no scenario would have imagined it, the lovers find themselves reunited as a couple without financial cares and are realising their dream of running a successful film company. The drawback is not only that they are prisoners, but that that their high-profile in the North Korean film industry has made them traitors in their own country and everyone but their children are suspicious of them. Still, after five-years the lure of freedom prompts them to plot their escape.

While we are lucky to have the film at all, the events occurred long ago and Shin’s death in 2006 means we do not his personal narration to complement Choi’s. We do, however, have testimonies from Shin and Choi’s two children; a ‘Court Poet’ to Kim Jong-il and an ex CIA agent who had allegedly debriefed the pair when they defected to the USA, to take up the slack.