Joyce Glasser reviews Pasquarosa: From Muse to Painter (at the Estorick Gallery until 28 April 2024)

The annals of art are strewn with female painters and sculptresses who first posed as models for famous male artists. If they were lucky, which was not the case with Picasso’s muses Fernande Olivier and Dora Maar, or Rodin’s muse, lover, pupil and assistant, Camille Claudel, the models were supported and their careers blossomed with their male counterparts. Such was the case with Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s model and wife Elizabeth Siddal, Renoir and Toulouse Lautrec’s model Suzanne Valadon and, in Italy, with Pasquarosa Marcelli (1896-1973).

Like Valadon, Pasquarosa as she was called, was beautiful, but, born into an impoverished, rural family, had few prospects. At 16 she headed to Rome where, with her willowy body, she became a sought after model. After meeting the painter, decorator and illustrator Nino Bertoletti, she became exclusive and they married.

While Bertoletti encouraged Pasquarosa and introduced her in Rome’s literary and artistic circles, in his large oil painting The Family, from 1930, he painted her, not as an artist but as a doting mother. Pasquarosa is reading to her younger son, sprawled on her lap, while her older son strums on a guitar.

The reading is significant, however, as we are told Pasquarosa arrived in Rome illiterate. She was eager to learn and it wasn’t long before she took up painting and was reading the books Bertoletti recommended as well as those given to her by the couple’s writer friends, including Luigi Pirandello.

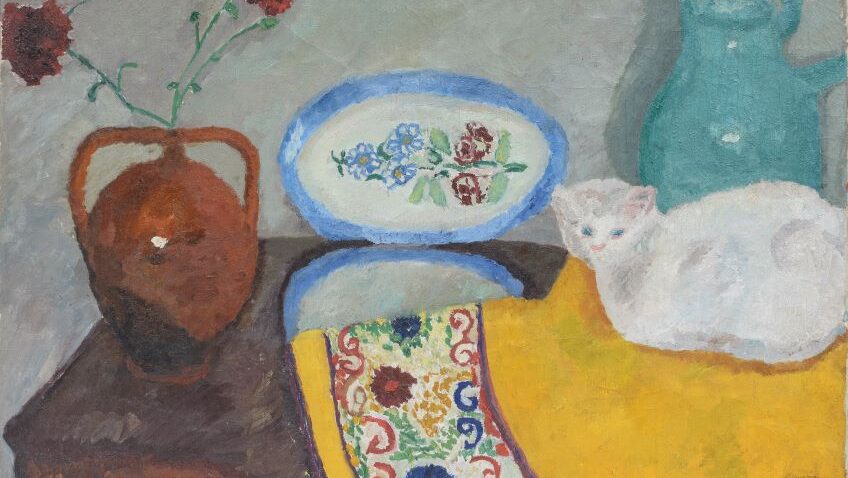

When the couple moved into the communal artists’ studio in Villa Strohl-Fern, Pasquarosa was surrounded by working artists who encouraged her. Within three years of picking up a brush she was exhibiting her work with the Rome Successionists. Travelling widely in the 1920s she saw the work of artists such as Van Dongen and Matisse whose influence is obvious in her best still lives, although her palette is completely her own. In 1929 she had a breakthrough exhibition in London’s Arlington Gallery and went on to exhibit in the Venice Biennale in 1930 and the Rome Quadrennial in 1931.

Her style was much closer to Winifried Nicholson’s (Ben Nicholson’s wife) and the English school of “naïve” painters than to the Italian Futurists. But she was no Alfred Wallis – the sailor from Cornwall who began painting naïve seascapes at the age of 70 – for her naïve style was inconsistent. A charming Hyacinth of 1916 shows a sole flower in a pot on a burgundy tablecloth, the light purple of the flower and the vertical green leaves marrying the dowdy table cloth with a modernist wallpaper background of green, yellow and orange.

There is nothing naïve about Zinnias from 1933 an accomplished still-life of a brass pot bursting with beautifully painted yellow, orange, red and white flowers complemented by a diagonal tablecloth in complementary colours that liberate the flowers while referencing the background: a mix of grey, green and brown. Flowers in a Mirror from 1949 is frilly and decorative in an old-fashioned, amateurish way.

Although most of the paintings are still-lives with flowers, there are several exceptions. A rare figurative painting is a small, early nude in a green landscape, made in a naïve, spontaneous style. The absence of outline seems to free the blocks of colour, equating the liberating feeling of nudity with the act of painting. A jug – almost personified – is visited by a thirsty bird as though they are balancing “beak to beak,” and a landscape from 1962 makes us wish there were more.

Again, we see Pasquarosa’s predilection for colour over line in an atmospheric, wild landscape with its patches of colour forming shrubs and heathland tumbling into distant mountains below an uncertain late afternoon sky. Everything is horizonal – even the mountain range – save two small trees that seem to be communicating to one another on a windy summit.

Still, when we consider how, in the 1960s, the world was exploding with new ideas – reactions to the world and the art of the 1950s – such as Op Art, Pop, Minimalist and Conceptual Art, this landscape, while lovely, is hardly profound stuff. If we think of the ground-breaking flowers painted by the American painter Georgia O’Keefe, whose life spanned that of Pasquarosa, or the astonishingly original work of another contemporary, Frida Kahlo, who was tearing up the rule book and creating feminist art, you might admire Pasquarosa’s joy of painting without overstating her position in the history of art.

Contemporary reviews of her work focused as much on her story: illiterate peasant girl exhibits her art at the Venice Biennale, etc., as on her art. The exhibition cannot resist this either, showing us home movies of the couple socialising (no art in sight) and an entire wall of Bertoletti’s portraits of her.

For those wondering about the flourishing of Pasquarosa and Bertoletti’s art during the thirties and forties, if their social circles included the leftist politician, writer and doctor Carlo Livi, a flattering friend was the painter, stage designer, illustrator and critic Cipriano Efisio Òppo. He became a deputy to Parliament and, in 1932, artistic director of the Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution.

Another friend of the couple was Giogio de Chirico, who, after mingling with the Parisian Avant Garde with his Metaphysical masterpieces, turned reactionary, slamming all modern art. A marvellous letter in the exhibition describes Bertoletti’s low opinion of the peripatetic artist at their first meeting in 1919. It’s a good thing de Chirico, who was hardly generous with praise or kind words, never read that, and perhaps because Bertoletti never posed a threat, the two became good friends.

In his memoirs, de Chirico describes Bertoletti as “intelligent, cultivated, educated and normal.” The best he can say for his art is that “he has had the courage never to get mixed up with the schemes of the so-called modernists”. If De Chirico was jealous of anything it was Bertoletti’s stable lifestyle with Pasquarosa. In his memoirs De Chirico writes, ‘he leads a well-balanced and regular life: during the more than twenty-five years since I have known him, he has only moved house twice whereas during the same period I have moved house twenty-one times.’