Joyce Glasser reviews Archipenko and the Italian Avant Garde (Estorick Collection until September 4, 2022)

This is your last call to dodge the strikes and head for Highbury Islington tube/overground station in London, if you fancy a weekend away or day out to see a rare showing of Ukrainian artist Alexander Archipenko. The two room exhibition is easily “doable” in 60 to 90 minutes, but take a break in the lovely café, or relax in the outdoor terrace to contemplate this unusual and successfully curated exhibition before returning to take a final look.

Archipenko’s drawings, paintings, collages and sculptures are worth that second look, but this show is more ambitious. Curator Maria Elena Versari wants to show us new links and spheres of influence, particularly between Archipenko and the Italian Avant Garde in the years after World War I. It is one thing to present an artist to the public, but another to show that artist’s influence on those in other countries and from younger generations, while also proposing a cross fertilisation of ideas with contemporaries, older and younger.

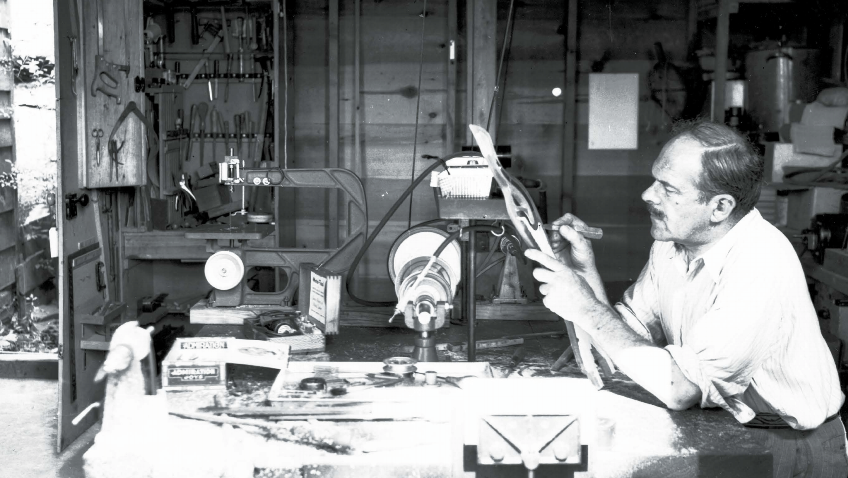

Although Archipenko was not Italian, he met the gallery’s founder, the American Eric Estorick, in the late 1950s. Estorick, who with his Italian wife was building the largest collection of Italian futurist art outside of Italy, organised several exhibitions of the artist’s work.

Born in 1887 (six year’s Picasso’s junior) in Kiev, it wasn’t long before Archipenko left his schooling in Moscow to head to Paris, the art capital of the world at the time. There he joined a group of young sculptors who were trying to escape the shadow of Rodin whose works he compared to the contorted casts of humans from Pompeii: bodies frozen in despair.

The Romanian sculptor, Constantin Brancusi, who was twelve years Archipenko’s senior, gravitated to Paris around the same time agreed that ‘When [the Greeks] depicted contortion and suffering in their sculpture, it was the beginning of their decline.’ Brancusi left Rodin’s studio after two months, saying, ‘nothing grows under big trees’ and began his ground-breaking modernist sculpture. We can see the Brancusi influence in the sensually smooth, aesthetically pleasing, Reclining figure (conceived in 1921, cast in 1956) but to see Archipenko’s true genius, walk around the back of the piece for the detail.

If Archipenko was not going to be a follower of Rodin, where would his inspiration come from? This was the very question in Paris at the time. Surprisingly, it came from the French philosopher, Henri Bergson’s 1907 book Creative Evolution, which argued that the creative impulse was just as vital to the human species as Darwin’s natural selection.

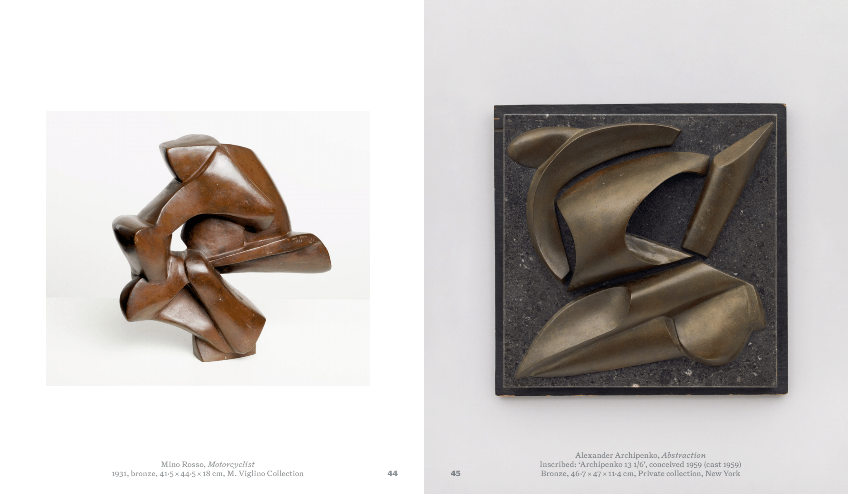

Archipenko was not beginning with a blank slate. In Moscow he had seen constructivism, and in Paris, he was influenced by the Cubists (Medrano II 1913-13, Standing Woman and Still Life 1919) and the Futurists (Walking Man 1914). It was Archipenko’s interest in analytical cubism to express dynamism that put him on the Futurist’s radar and the artists Severini, Soffici, Boccioni and Carra, followed his evolution. Have a look at Woman Standing (1916, cast, 1969) and then see that sculptures influence on Mino Rosso’s Feminine Architecture of 1928. Similarly, consider Archipenko’s Madonna of the Rocks (a redistribution of volumes) of 1911-1912 and see how Rosso has used it for his Rugby Players of 1930.

But the great poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire was not going to resign from a lucrative magazine job over just any artist. Writing on a 2014 Archipenko show, he claimed, ‘the originality of Archipenko’s temperament does not at first glance seem to reflect any influence from the art of the past. Yet he has taken what he could from it; he realises he is capable of going beyond it audaciously’ and went on to praise the sculptor. Apollinaire was defending Archipenko against an attack published by a conventional rival art critic in the same paper, I’intransigeant’ (Apollinaire on Art: Essays and Reviews, Da Capo Press, 1972. ed. Reroy C Breunig).

Apollinaire, who took all punctuation out of his debut collection of poems in 1913; wrote his second in calligrammes (shapes) and tried to write a cubist poem, Les Fenêtres, (The Windows) to express the joy of Robert Delaunay’s series of the same title, recognised another maverick when he saw one.

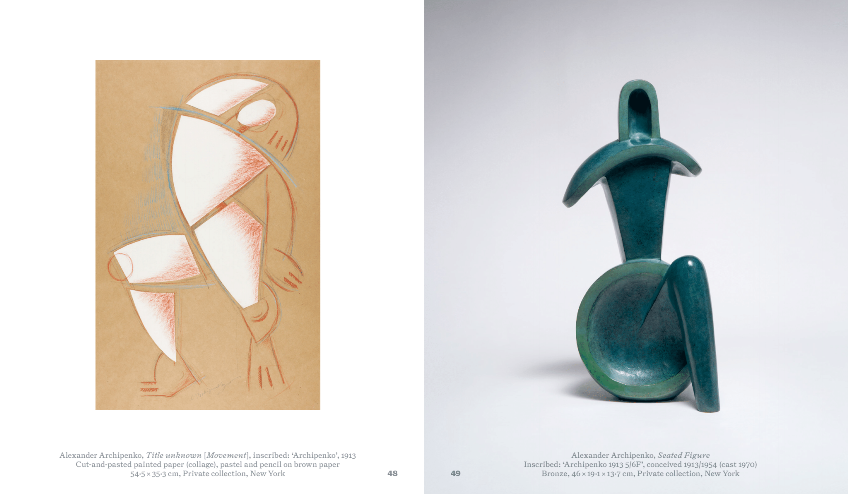

You wouldn’t catch Brancusi messing up the purity of his smooth, elegant monochromatic surfaces with colour, but the Ukrainian, as Apollinaire reminded his readers, used the past where it pleased him, including the pre-Columbian art that he loved. His “sculpto-paintings” (collages that predated Frank Stella and Robert Rauschenberg) like his 1917 Figure is a case in point. The curator cheekily places Giorgio de Chirico’s The Revolt of the Sage (1916) next to Archipenko’s Architectural Figure, a kind of building on top of a Romanesque arc in painted wood, the colours echoing the de Chirico and the whole, an echo of de Chirico’s architectural landscapes. Archipenko also worked in an astonishing variety of materials, terra cotta, painted wood, bronze, Bakelite – ever pushing the boundaries of sculpture further.

But if Archipenko is remembered for one thing it is the introduction of negative spaces in three dimensional sculptures. This interest began with unusual concave and convex shapes like the gorgeous, ground-breaking Seated Figure of 1913. Compare this with his Seated Woman of 1920 to see how the concave shapes have disappeared and are now negative spaces, or Woman Standing of 1916 that influenced Rosso’s Feminine Architecture. When he combined the negative and positive spaces new shapes and a new fluidity and dynamism appeared.

If you remember Bergson, these negative spaces were not voids, but spaces to be filled with thoughts, memories, desires, images and the like. Sometimes less is more.