Joyce Glasser reviews Klimt and The Kiss (October 30, 2023) Cert 12A, 89 mins. In cinemas.

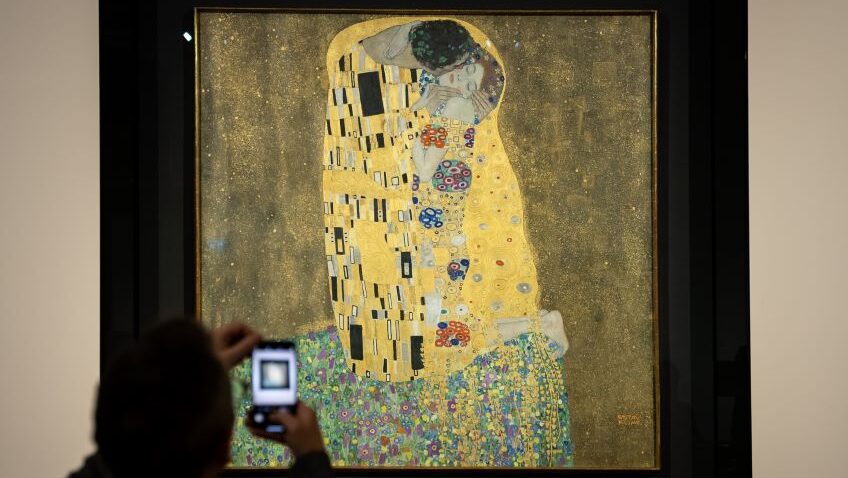

How can Seventh Art Productions, the production company that brought you the Vermeer film earlier this year, top that one? The answer is with Klimt and The Kiss, where you get a biopic, tour of key locations in Klimt’s life and a fascinating, brilliantly illustrated art history lesson all in one. As the title suggests, the focus is on The Kiss, and the intelligent, insightful commentators lead us step by step toward a greater understanding of this painting. Just as viewers to the Louvre rush to see the Mona Lisa, and viewers to the Mauritshuis in the Hague dash to The Girl with the Pearl Earring, so viewers to the Belvedere in Vienna congregate around The Kiss, an enigmatic golden icon of modernity beckoning worshippers of art.

Because of the multitude of metallic flakes and gold leaf used with the paint (we are given a demonstration in the film), The Kiss literally radiates emotion and also spirituality. “You’re dazzled initially; you’re disoriented. You don’t quite understand what’s going on,” says Dr Sabine Wieber of the University of Glasgow – the city whose art nouveau output influenced Klimt. She is talking about the painting The Kiss from 1907, but she could also be describing the feeling of kissing a lover for the first time.

Various experts return us to the painting, enriching it with different perspectives. Several of the experts are from The Belvedere Museum that purchased The Kiss for a large sum in 1908, at the height of Klimt’s fame, just five years after it was established as Vienna’s modern art museum.

Dr Ivan Ristic of Vienna’s Leopold Museum adds: ‘only in the second instance do you think about the kind of kiss it is.’ Some consider it is Gustav himself in a passionate embrace with his lifetime companion and lover Emilie Flöge, both kneeling on a prairie of colourful wild flowers. To their right is an abyss. Is love saving them from the abyss or pushing them toward it?

When Emilie and Klimt met he was 29 and she was 17, but their much photographed holidays at Lake Attersee were not so much trysts as Flöge family gatherings. It is believed that Emilie made garments (the shop she owned specialised in “breathable” comfortable clothing for the bohemian modern woman) for some of Klimt’s paintings.

But there are other interpretations. ‘Klimt had no interest in portraying character traits. He subjected women to his artistic will and inserted them into his decorative design,’ observes Belvedere curator Stephanie Auer. The kneeling, barefoot woman is imprisoned, or smothered in the much larger man’s embrace as well as in her brightly coloured robe from which her pale face emerges. Her robe has the bright coloured circular patterns the Swedish artist Hilma Af Klint was painting in 1907 and the male’s robe is made of dark rectangular designs, resembling a cemetery, and similar to those of the Devil with a club in Death and Life, painted in 1910. The female’s eyes are closed, either in pleasure or, as in Klimt’s later, cycle of life paintings – that may reflect the mood of WWI – his old, dead or dying women.

‘The Kiss only could have been made when it was, where it was, and by whom it was,’ states Cultural historian Dr Janina Ramirez. ‘It was so uniquely fin de siècle Vienna.’ And, as we see, Vienna in 1900 was the cultural capital of the West.

To understand The Kiss you have to know something about Gustav Klimt and the times in which he lived for he did not operate in a vacuum. Just as early on he sought to please the conventional Hapsburg taste, so, with fame, financial security and confidence, he underwent a startling transformation, and set about shocking the bourgeoisie. The Kiss was the culmination of a decade of Jugendstil (Youth Style), an Austrian form of art nouveau. It was officially born with the Vienna Secession Movement, formed in 1897 by many of the foremost artists, sculptors, architects and graphic designers in the country. In a contemporaneous photo in the Secession movement building, designed by Joseph Maria Olbrich, and painted white with a golden dome like a temple to art, Klimt sits enthroned like its priest.

In 1901, Klimt decorated the white wall with his magnificent frieze to Beethoven’s 9th Symphony (Ode to Joy) to celebrate the 14th Secessionist exhibition. At the end of the extensive work, – which can still be seen today in situ, – is Klimt’s first unambiguously joyous Kiss – a nude couple embracing, the man all but obscuring the woman. The stylised, mostly female figures in the Frieze appear to sing like musical notes and the Frieze is a then optimistic Klimt’s first kiss to the world.

But Klimt did not always paint like this. Although born into poverty just outside of Vienna in 1862, the second of seven children, Klimt showed an early talent for drawing and managed to get into the school of Applied Arts and Crafts, (now the University of Applied Arts) where he trained in architectural drawing. His teachers encouraged him to branch out and he became adept at painting allegorical murals, a genre he was to update in his art nouveau manner (we pause before Judith and Holofernes, 1901). His mother dreamt of being a musician – hence perhaps the Beethoven Frieze – and his father was a gold engraver, as was one of his brothers.

Although the attraction to gold was bred into him by this early exposure, until the early 1890s, he painted in the Academic style of his training and made his name painting murals on municipal buildings along the newly built Ringstrasse – the symbol of the pinnacle of the Hapsburg Empire with its lingering aristocracy and burgeoning bourgeoisie. In 1888, aged 28, Klimt received the Golden Order of Merit from Emperor Franz Josef I of Austria. A reclusive bohemian who dressed in long, loose robes, lived with his mother, Klimt never married but had countless mistresses, and reportedly 14 children, and whose pornographic drawings of women he picked up off the street shocked the buttoned up Vienna society. But he was the talk of the town.

Commissions for portraits of wealthy wives and daughters began pouring in and Klimt became known as the painter of women, including the famous, increasingly decorative portraits of Adele Bloch-Bauer – a Jewish patron – including one dubbed The Woman in Gold. The film treats us to all of the great portraits, chronologically.

We also see, in an impressive series of comparisons, how Klimt absorbed and yet transformed influences from such painters as Van Gogh, Rodin (note his famous sculpture, The Kiss), John Singer Sergent, James Whistler, Monet, Matisse, and especially, the Dutch symbolist artist Jan Toroop and the British artist Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh. She was the wife of Charles Rene Mackintosh, exiled for corresponding with Austrian designers and architects just before WW I.

Klimt was undoubtedly the high priest of Vienna 1900, but the film concludes with the tantalising question, “What is Klimt’s place in the history of art?”