Joyce Glasser reviews Viceroy’s House (March 3, 2017)

Gurinder Chadha (Bend it like Beckham) has faded from the limelight since her last critical and box office success, Bride and Prejudice, in 2004. Her new film is the lavishly produced Viceroy’s House about the 1947 Partition of India, the consequences of which have scared the subcontinent ever since. According to Chadha, she wanted to make a film ‘in the same tradition as David Lean’s A Passage to India and Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi.’ Well, a peckish Gandhi look-alike (Neeraj Kabi) does appear, but David Lean it isn’t. It is not even vintage Gurinder Chadha, which is all the more surprising, as the talented filmmaker is digging into her roots. If you know nothing about the 20th century history of India, the film might be edifying, but the entertainment value is curiously limited.

The film begins with a caption: History is Written by the Victors, and then ‘Delhi, India, 1947.’ This is a curious caption because, most commendably, Chadha makes a point of showing that there were no victors in Partition. For many, including Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Denzil Smith), the Muslim leader who insisted upon a separate Muslim country, India’s minority population won in the long term. But there was a cost. Some 12 million people became migrants, with thousands, if not millions of Muslims, living peacefully beside Hindu neighbours, forced to flee to the newly created Pakistan. In addition to those who died or were killed in religious skirmishes, an estimated 1.26 million Muslims went missing in the journey to Pakistan.

The film begins with a caption: History is Written by the Victors, and then ‘Delhi, India, 1947.’ This is a curious caption because, most commendably, Chadha makes a point of showing that there were no victors in Partition. For many, including Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Denzil Smith), the Muslim leader who insisted upon a separate Muslim country, India’s minority population won in the long term. But there was a cost. Some 12 million people became migrants, with thousands, if not millions of Muslims, living peacefully beside Hindu neighbours, forced to flee to the newly created Pakistan. In addition to those who died or were killed in religious skirmishes, an estimated 1.26 million Muslims went missing in the journey to Pakistan.

The film opens with dozens of servants cleaning the tennis court, pool, marble floors and pillars of the Rashtrapati Bhavan, or Presidential Palace, built by Edwin Landseer Lutyens in 1929, to which Chadha gained excess for exterior shots. As the official home of the President of India, it is the largest official residence of a head of state in the world. It is therefore symbolic of what was wrong in a country where the large majority of the population was illiterate and lived in poverty. But inside the palace the excitement is palpable. A new Viceroy has been appointed to transfer power to a democratic India. Voices murmur that ‘the War did it – England can’t afford to be here anymore.’ Two Indian servants discuss that England is all ‘slums and bomb sites.’

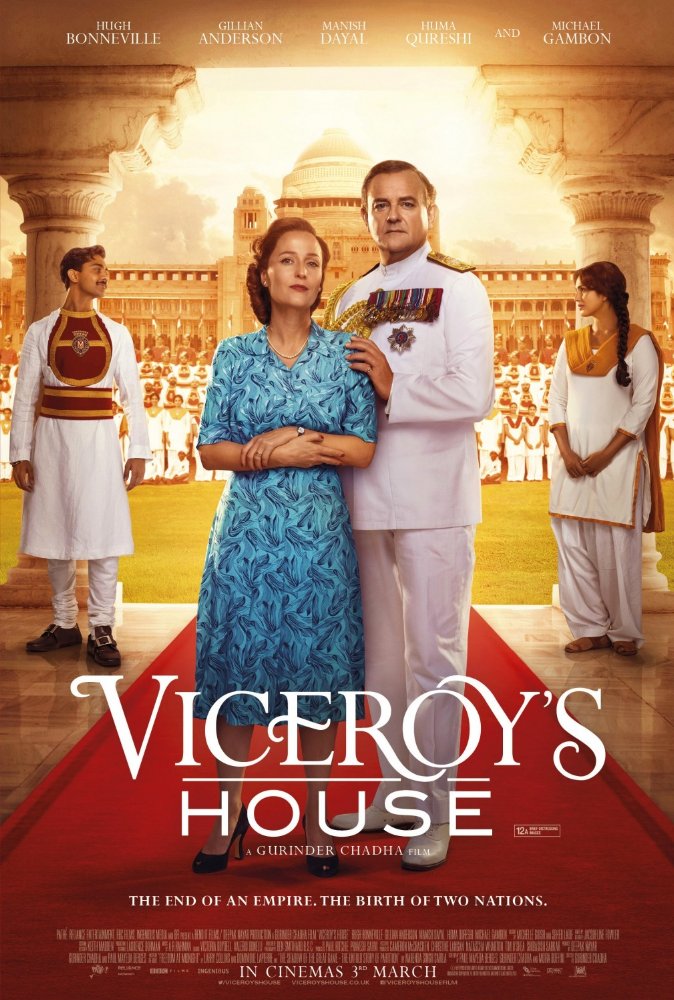

The arrival of Lord (Hugh Bonneville in Downton Abbey mode), ‘a great man who freed Burma,’ in the words of one servant, and Lady Edwina Mountbatten (Gillian Anderson, progressive but aristocratic to the core) is the cause of this flurry of work.

It is not long before Nehru (Tanveer Ghani), Gandhi (Neeraj Kabi) and Jinnah are in meetings with Mountbatten and General Hastings Ismay (Michael Gambon), Mountbatten’s advisor with an agenda. Lady Edwina impresses with her liberal open-minded credentials. She tells the chef she wants Indian, as opposed to English, food served and rules that at all dinners and state occasions, 50% of the guests will be Indian. She sacks an English worker who says, ‘I wish they wouldn’t come so close,’ referring to a servant, sweating in the unbearable heat. But it is, of course, too little, too late, and the Mountbatten’s soon realise it.

In production notes and interviews Chadha says that the idea was to show how the high-level negotiations ‘upstairs’ at the Viceroy’s House affected the people ‘downstairs’. She chose this upstairs/downstairs structure to avoid scenes of the violence that was erupting all over India in anticipation of a divide along religious lines.

The ‘people’, however, are represented by a pair of attractive star-crossed lovers who have responsible (no manual labour here) positions in the Viceroy’s House. Aalia (Huma Wureshi) is Muslim, and her lover Jeet (Manish Dayal, The 100 Foot Journey), is a liberal Hindu. Both are trapped in a sub-plot replete with clichés, melodrama and improbable good fortune. For Aalia is promised to a Muslim suitor with a nice car headed for Lahore, and she feels duty bound to take her father (the late Om Puri) to Pakistan, unaware that he cares more about her happiness.

This Romeo-and-Juliet story might represent the ‘people’, but what about Chadha’s grandmother, to whom the film is dedicated? Surely Chadha could have told a more interesting and convincing story about this relative displaced by migration?

When it comes to Partition, though, the ‘downstairs’ is once again upstaged by the ‘upstairs’. For the real tragedy here is ‘Dickie’ Mountbatten’s and line-drawer Cyril Radcliffe’s (Simon Callow) impossible, thankless task. Radcliffe, who has two weeks to decide the fate of 361 million people, admits to Dickie that far from being an expert on the subcontinent, he has never been to India.

In the film’s most revealing scene, an agonising Mountbatten and his even saintlier wife (frolicking with Nehru here) discover they’ve been duped by Churchill, Lord Ismay, and Jinnah who have sealed a secret deal. In a new slant on the negotiations that are the subject of Howard Brenton’s brilliant play, ‘Drawing the Line’, we learn that Churchill wants access to the oil reserves in a strategically carved out Pakistan. He did not trust Nehru, with his Socialist leanings and ties to the USSR to deliver them. This theory of Partition is not Chadha’s, but she does use it to enhance the contemporary relevancy of this historic blunder.

You can watch the film trailer here: