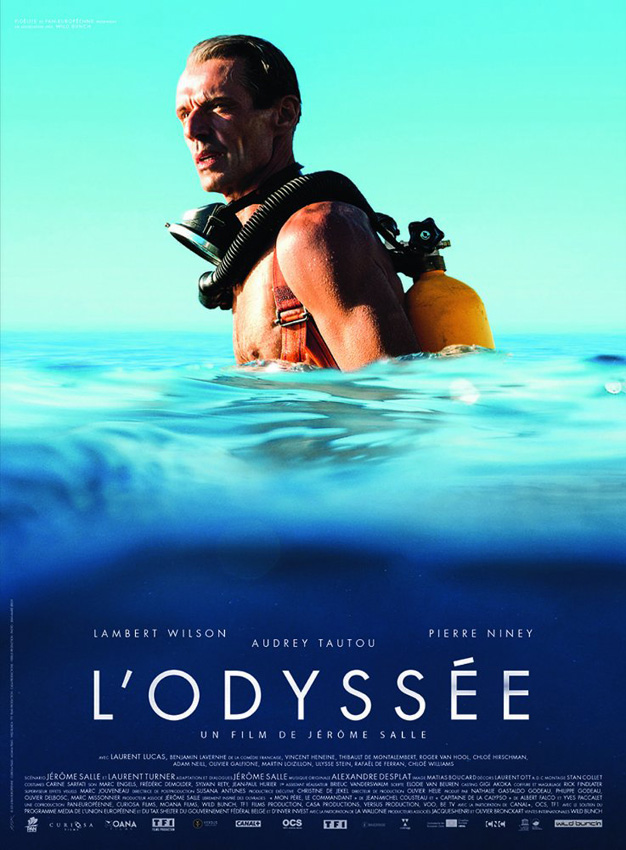

Joyce Glasser reviews The Odyssey (August 18, 2017) Cert.PG, 122 mins

For anyone over 50, the prospect of a lavish biopic of Jacque-Yves Cousteau is a welcome one and not only for anticipated views of underwater kingdoms, turquoise oceans and melting ice caps. We grew up with Cousteau’s television programmes; were around in 1975 to hear John Denver’s rapturous tribute, Calypso; read about his Congressional Medal of Freedom from Ronald Reagan in 1985; and saw Wes Anderson’s parody/homage The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou in 2004. You might even be a life member of the Cousteau Society for the Protection of Ocean Life, set up in 1973 and still going.

Yet, as a film, The Odyssey has a problem. The more multi-faceted and successful a person is, the more difficult to adapt that life for cinema. Making a biopic of the legendary WWII hero, naval officer, inventor, scientist, adventurer, author (The Silent World, 1953); Palme D’Or winning filmmaker (The Silent World, 1956); entrepreneur and conservationist Jacques-Yves Cousteau is a daunting task and proves too much for director Jérôme Salle. Salle, and his co-writer Laurent Turner, fail to give the film a focus and direction or, with one exception, to recreate the explorer’s sense of awe and wonder.

Yet, as a film, The Odyssey has a problem. The more multi-faceted and successful a person is, the more difficult to adapt that life for cinema. Making a biopic of the legendary WWII hero, naval officer, inventor, scientist, adventurer, author (The Silent World, 1953); Palme D’Or winning filmmaker (The Silent World, 1956); entrepreneur and conservationist Jacques-Yves Cousteau is a daunting task and proves too much for director Jérôme Salle. Salle, and his co-writer Laurent Turner, fail to give the film a focus and direction or, with one exception, to recreate the explorer’s sense of awe and wonder.

The very nature of Cousteau’s personal odyssey obliges the filmmakers to span the decades; but turning thirty years of a workaholic overachiever’s life into a film means expediency triumphs over artistry. The filmmakers make ample us of expository dialogue and montages to cover the passage of time, while short, staccato-like scenes dramatise pivotal episodes and encounters.

Putting aside for a moment an opening flash forward, the film begins in 1949 when Cousteau quits the French Navy to found the French Oceanographic Campaigns (FOC). In a revealing early scene, Cousteau, stepping forward to replace his stage-struck, humiliated collaborator, Philippe Tailliez (Laurent Lucas), announces the commercialisation of the Aqua Lung in an elegant speech which attracts applause. In the speech he equates man’s ability to swim like a fish in underwater weightlessness to the realisation of man’s age-old dream of flying.

The reference to flying in this speech is double-edged and brings us to that flash forward. If David Lean can begin Lawrence of Arabia with Lawrence’s accidental death so can Salle and Turner – only it is not Jacques Cousteau who dies in the depicted 1979 plane crash. It is his son: the handsome, 39-year-old pilot, Philippe Cousteau (Pierre Niney), heir to his father’s empire and vision.

And this is another problem with The Odyssey. It is sometimes unclear whose film this is as Philippe is such a chip-off-the-old-block and such an accomplished individual in his own right. Their lives are also intertwined because of some serious father-son issues stemming in part from the decision to send Philippe to boarding school where he was miserable. Philippe, who spent summers on his father boat, is struggling to emerge from under his famous father’s shadow. The more he strives for attention and praise, the more reckless Philippe becomes. In one scene, Philippe competes with Jacque’s right-hand man on The Calypso, Albert ‘Bebert’ Falco (Vincent Heneine) putting lives in danger. Later, however, Philippe’s expertise in aerial photography and oceanography help distinguish Cousteau’s films, while is interest in the environment, proves a catalyst for his father’s transformation.

Along with Jacques wife Simone (Audrey Tautou), Philippe also has issues with his father’s infidelity. This part of the family’s life is tactfully acknowledged and glossed over, despite the fact that Cousteau had two children in the 1980s with the woman who, after Simone’s death in 1991, became his second wife. Tautou gives her best – that is, most bearable, convincing and adult – performance as Jacques’ long-suffering wife, but her part is underwritten. When Jacques quits his Navy job to risk everything on The Calypso, she insists on selling her mother’s jewels to finance her husband’s dream. After one big confrontational scene with Jacques over his womanizing, however, Simone has little more to do than hang around the ship depressed and tipsy.

We learn that Cousteau’s relationship with oil companies began when he negotiated free fuel for his expeditions in exchange for scouting locations for off-shore drilling. Cousteau did extensive commercial work in oil exploration before turning to conservationism in collaboration with Philippe. This transformation could have been the peak of the character’s arch if not the film’s focal point, but it is presented in a kind of continuum. And despite some excellent underwater cinematography, and beautiful scenery, the only time we experience the thrill and the wonder that a diver might feel in an underwater kingdom is when father and son embark on a research trip to Antarctica.

Lambert captures Cousteau’s steely determination, energy, manly athleticism, and his burnt-out exhaustion from overextending his television production company, but the portrait is not a sympathetic one. Pierre Niney’s performance is adequate, but despite Philippe’s psychological struggles and very real accomplishments, you might find it hard to empathise with him either. Oddly for a long film so packed with a range of tragedies and triumphs, the film leaves us with an emotional void that not even Alexandre Desplat’s insistent score can fill.

You can watch the film trailer here: