Joyce Glasser reviews The Ice King (February 23, 2018) Cert 12A, 89 min.

Watching The Ice King against the background of the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics reminds you how much male figure skating owes to John Curry and to what extent he remains unrivalled in his balletic grace and in the nuanced beauty of his choreography. Many British people over 50 will know that John Curry won an Olympic medal (it was the Innsbruck 1976 Olympic Gold) and some might have seen him perform live at the Albert Hall, where, for the only time in history, the stage was flooded for Curry’s Symphony on Ice. James Erskine’s (Pantani: The Accidental Death of a Cyclist; The Battle of the Sexes), compelling and compassionate documentary will be equally riveting for those who have never heard of the single-minded boy from Birmingham who became a Billy Elliot on ice.

The comparison is apt. Growing up in the 1950s, while his two brothers were out playing football John, from the age of 7, wanted to be a dancer. Though his father nixed the idea, he did allow John to take staking lessons because skating was considered a ‘sport.’ It is ironic that Curry set out to change that classification in everything he did. ‘Skating,’ Curry says, ‘became the escape where I could be free and alone.’

There is another irony in this statement, as in Curry’s personal life he was always complaining about being alone and loneliness. If in this early statement he was referring to getting away from his stifling father, John had a romantic notion of all consuming and long-term love that never materialised. Erskine devotes ample time to John’s various love affairs (neglecting the most high profile, his relationship with Alan Bates) but most of the film is devoted to Curry’s art.

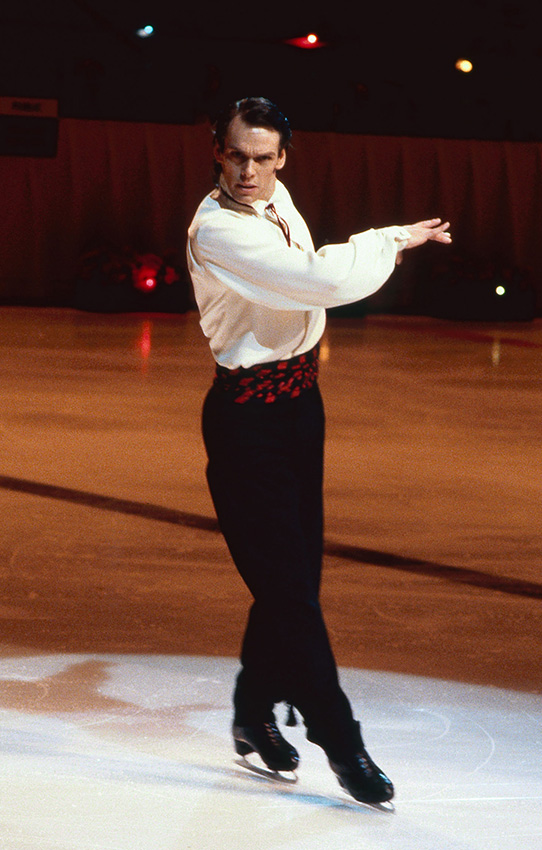

And this is where he strikes gold with a newly discovered recording of Curry’s masterpiece, Moonskate. In Curry’s pensive solo work, choreographed by Eliot Feld, with lighting by Jennifer Tipton, his feet barely leave the ice. This is ice dancing stripped of all of the tricks and gymnastics of skating. It is modern dance – on ice and is so expressive of Curry’s state of mind that the spectator is turned into a voyeur.

If Tonya Harding struggled with the social elitism in Olympic ice skating, Curry struggled with the macho image of the sport. ‘As I became a young man, I was told not to be so graceful,’ he reflects. ‘It was accepted as a boy, but not as a young man.’

And Curry was a beautiful young man who appealed to both sexes. Tall and handsome with curly locks and a perfect dancer’s body, he ignored the advice to be more athletic than graceful and was convinced that ‘the music told me exactly what it wanted me to do.’ This does not seem to be the case with Donald (double axel) Jackson, a celebrated Canadian skater. Erskine gives us a cheeky comparison with a clip of Jackson’s style. This will not be John Curry’s.

Along with archival footage, recently uncovered, unique recordings of his performances; interviews with the sometimes aloof and elitist sounding skater and the talking heads of some of Curry’s friends, actor Freddie Fox reads from Curry’s personal correspondence throughout the film.

Curry had one dream: to start his own ice dancing company and change the way people looked at ice skating. But he knew that the only way to attract investors and audiences was to win Gold in the Olympics.

Fortunately, his skating had attracted the sponsorship of Ed Mosler, who sent him to train with the top coach in the world, Carlo Fassi, all expenses paid. Curry eventually moved to Colorado, forcing himself to focus on the boring ‘figure skating’ part of skating (as opposed to the interpretive free style in which he excelled) before heading to the 1976 European Championships.

But if Tonya Harding battled with class prejudice, Curry had another problem: the cold war. In an interview Curry says, ‘when you have five Eastern Block judges you kiss your chances goodbye.’ Asked if he is saying the system is corrupt, he answers, ‘yes, it is.’

At the European Championships, Curry’s routine to the music of Ludwig Minkus’s Don Quixote is so sublime that a Czech judge breaks rank and Curry wins Gold. There were no favourites at the Innsbruck 1976 Innsbruck Olympics, where a combination of faultless technical skills and grace made him the only choice for Gold.

The Gold medal is not only his passport to start a company, but an occasion to ‘come out’ at a time when it was taboo, despite the 1967 decriminalisation. In this he had an enormous impact on many young men around the world, and his fan male reflected it.

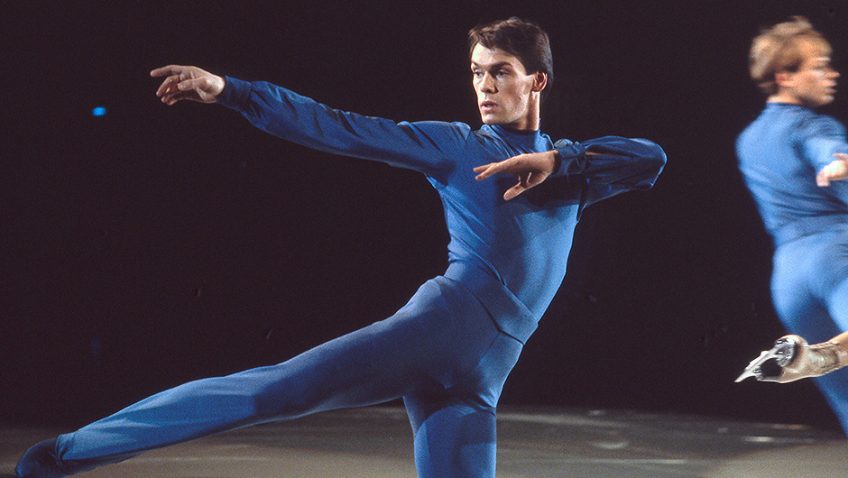

Once John starts his company, Erskine lets us enjoy his ambitious and gorgeous adaptations of classical ballets and astonishing new work from world famous choreographers such as Sir Kenneth MacMillan, Peter Martins and Twyla Tharp. Curry was a talented choreographer in his own right. He made a statement by premiering in a romantic version of Nijinsky’s The Afternoon of a Fawn. Such was the demand to see Curry skate that he was not only allowed to flood the Royal Albert Hall, but the Metropolitan Opera House stage in New York. When his dancers emerge to the music of Rossini’s William Tell Overture, his corps de ballet as it were, move with the precision and fluidity of dancers in Balanchine’s Jewels, only amazingly, they are gliding on skates.

Curry’s diagnosis of HIV in 1987 corresponded with the closure of the company and his semi-retirement. Erskine does not go into detail on the financial disputes with the staff, accountants and investors, but it appears Curry was more the artist than the responsible manager. Curry complained that he never made any money and the performances, although sold out to glowing reviews, lost money. By now very close to his mother with whom he lived (his father had died much earlier), he had one last contribution to make to ice dancing. A former skater in Curry’s company, Nathan Birch, who founded The Next Ice Age Company, asked him to help out on a routine to Strauss’s Blue Danube for four males. Curry choreographed and designed the costumes. The film ends with this extraordinary piece, a tribute to Curry and his legacy.

If his death at 44 cut short a life with so much more to give, it is perhaps less a tragedy than is the life of Tonya Harding, the subject of I, Tonya, a film also released this week. Curry had, after all, accomplished his two career goals in his short, extraordinary life. Even if the number of clean quad jumps a skater does still determines Olympic scores, Curry broke the ice and created a new art form.

You can watch the film trailer here: