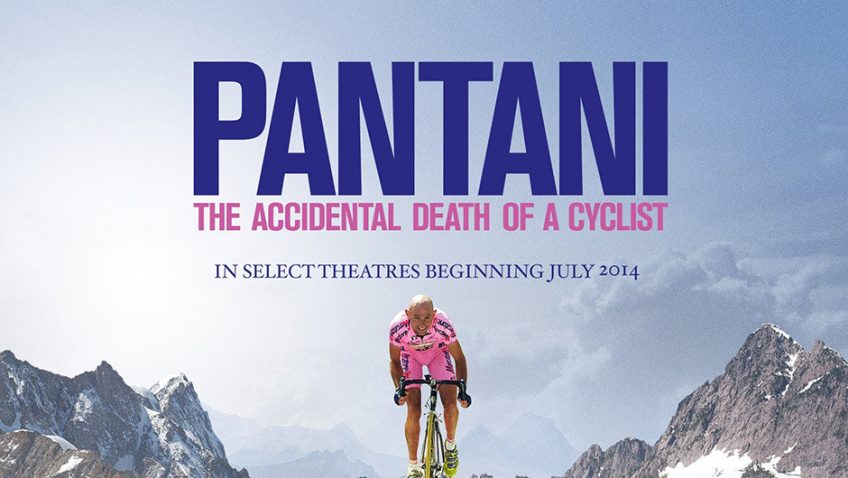

Joyce Glasser reviews Pantani: The Accidental Death of a Cyclist (May 16, 2014) Cert 15, 96 min.

Early this year, the documentary The Armstrong Lie told us everything we could ever want to know about the Tour de France doping scandal and the American ‘champion’ most associated with it. James Erskine’s documentary Pantani: The Accidental Death of a Cyclist covers similar ground, but focuses on one of Armstrong’s Italian competitors who appears to have been a casualty of the Armstrong Lie. The film argues that Marco Pantani’s untimely death was a consequence of the superhuman demands made of athletes; the cut-throat competitive environment and the commercialisation of the sport for television audiences. Still, it begs the question: is Erskine soft on Pantani?

Born in Cesenatico, Italy in 1970, Marco Pantani always loved cycling and assembling bikes to see how they worked. When you are addicted to cycling and faster on the climbs than on the flat stretches, you are a born Alpine cyclist. Even a near fatal collision with a truck in 1995 that left him with one leg shorter than the other after two years of therapy did not stop his career.

When there was no choice but to turn professional and join the Carrera Team, Pantani told his mother he would be quitting the sport because ‘it was a mafia.’ The tragedy is that he loved competitive cycling too much to quit.

Quitting was the farthest thing from his mind when, in 1998, he won both the Giro D’Italia and, five weeks later, the Tour de France, a feat that has never been matched. Bradley Wiggins is quoted as saying, ‘I never felt worthy of being in his company.’ And it is true, as Wiggins jokes, that ‘The Tour’ is the only sporting event that is so long that you need a hair cut half way through it. Yet six years later Pantani was found dead in a cheap hotel in Rimini at the age of 34. The cause of death was acute cocaine poisoning.

It seems that, like all pro cyclists in the late 1990s, Pantani was guilty of EPO, doping. In EPO, or blood doping, athletes are given erythropoietin injections to boost the body’s red blood cell count and facilitate the flow of oxygen around the body. This improves performance. Pantani never admitted it and the film does not go into detail on the evidence because at the time, there was no test to detect the hormone. If your red blood count was above a certain level, you were suspended. But, it can be argued, if everyone had the same advantage, the playing field was level and the TV viewers got a better show. So where is the harm?

Cycling is big business and no one really wants a level playing field. When Pantani ignored requests to back out or slow down in a race to increase the competition for spectators (and for the bookies), a blood test was taken and he was suspended. Depressed at the attacks on his name and of what he considered a conspiracy, and afraid of falling into a trap if he raced, Pantani did not enter the 1999 Tour de France, and started taking cocaine.

His tearful mother reflects: ‘I sent my son out to do sport because I thought it was healthy and provided good company. Sport should mean life, not death.’

This thought provoking documentary is worth seeing even if you sat through The Armstrong Lie; and perhaps, especially if you did.

You can watch the film trailer here: