Joyce Glasser reviews The Black Hen (December 9, 2016)

If the 32-year-old President of the Independent Film Society of Nepal, who is also an Assistant Professor in Film Studies, has just made his first feature-length film, you can imagine how difficult it is for Nepalese filmmakers. But in The Black Hen, writer/director Min Bahadur Bham is looking back to an even more difficult time in his life, and in his country’s history. From 1996 to 2006, the Nepalese Government, under its king, was engaged in a civil war against Maoist guerrilla insurgents, with an estimated 16,000 casualties. For two boys growing up in a remote village in Northern Nepal, these political divisions only add to the misery of Nepal’s socio-economic divisions – and frustrate their search for a valued hen.

Families, like that of young Prakash (Khadka Raj Nepali) are being torn apart by the conflict. Prakash and his older sister Bijuli (Hansha Khadka) live with their illiterate father in a one-room hovel on the property of the Headman whose grandson, Kiran (Sukra Raj Rokaya), is Prakash’s best friend.

Families, like that of young Prakash (Khadka Raj Nepali) are being torn apart by the conflict. Prakash and his older sister Bijuli (Hansha Khadka) live with their illiterate father in a one-room hovel on the property of the Headman whose grandson, Kiran (Sukra Raj Rokaya), is Prakash’s best friend.

But Prakash is an untouchable and Kiran’s family and society at large frown upon their close friendship. When the Maoists come to the village promising education for all, with good-looking young men dancing and chanting slogans, Bijuli finds it ‘interesting’ and stays behind when others start to leave. Bijuli has instilled in her brother the notion that education is their only hope of leading a better life. Bijuli has purchased a hen for Prakash to keep. He is going to sell the eggs to pay for their education. When Bijuli runs off to join the guerrillas she leaves money under Prakash’s pillow and entrusts the hen to his care.

Prakash’s father is ashamed of his daughter’s actions and fears for the family’s well-being. The Headman is a staunch supporter of the king and troops visit his home. Desperate for money for food, Prakash’s father sells the hen to an old man who plans to give it to his pregnant daughter in another remote village. When Prakash learns of the theft he and his father argue. Kiran joins Prakash in an attempt to raise money to buy back the hen with Kiran actually stealing money from his grandfather.

Meanwhile, Kiran’s sister, Uzhyale (Benisha Hamal), the local school teacher, is also affected by the political turmoil when her fiancée is kidnapped by the Maoists. Among the Maoist kidnappers is Bijuli who gives her brother some money with the promise that he tell no one he has seen her.

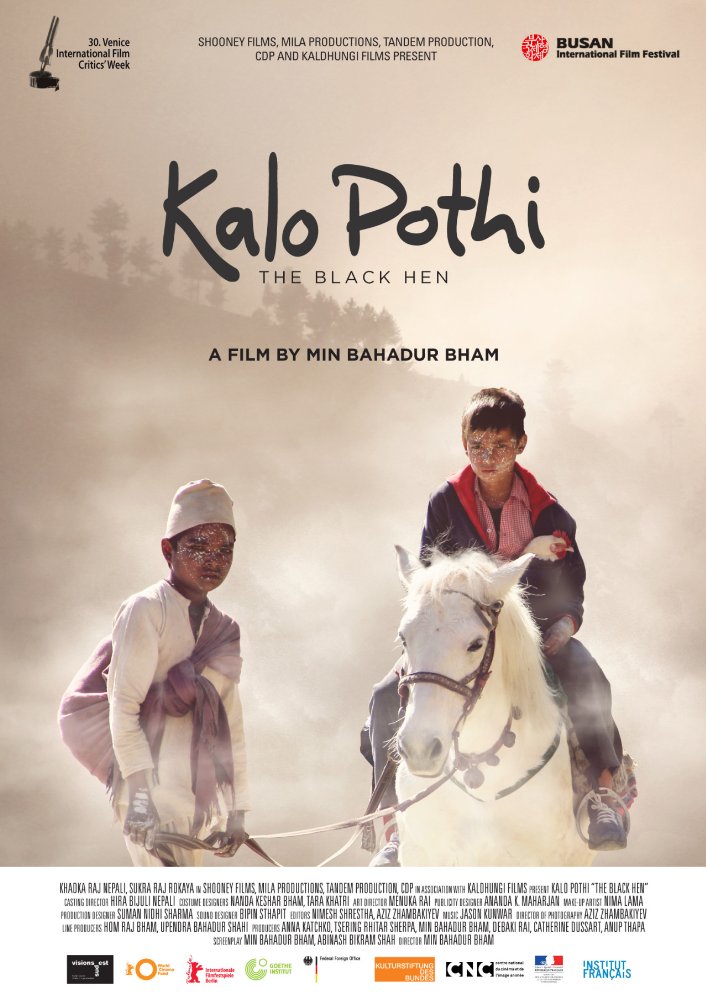

Using Kiran’s white horse, the two friends set out through the majestic mountains en route to the pregnant daughter’s village. In an endearing scene, Prakash rejects Kiran’s help, for fear of getting Kiran in trouble at home. For Kiran, their long friendship is more important and this might be the last time they can spend time together. So off they go into the unknown. On the second day of their journey they are caught in a Maoist ambush, and escape by lying still in a pile of bloody corpses.

The acting is unaffected, raw and convincing but the big star of the film is Nepal as shot by cinematographer Aziz Zhambakiyev. Under the director’s mind’s eye, he captures what would be the snow covered mountains and green valleys, the pine trees and noisy, pristine rivers that form what should be an idyllic landscape in which young boys can play. But play is consumed by a cycle of poverty aggravated by political unrest that is not of their making.

We gain additional insight into Prakash’s predicament through his vibrant dreams in which the death of his mother is entwined with the political unrest and the search for his hen. He emerges as a remarkable young boy, who, with the education he longs for, would go far.

Unfortunately, Min Bahadur Bham and his co-writer Abinash Bikram Shah do not make it easy on the viewer, at least not on western audiences. The early establishing shots are anything but. Not only does he use long shots so that we do not see who is talking, but as characters are named, we cannot always attach a name to a face. For the first twenty minutes, you might struggle a bit get a handle on the characters and their relationships to one another. It doesn’t help that in Nepal, middle-aged men are called Uncle and old men, Grandfather, or so it seems. The title is also curious as in the first shot of the film we see a peasant carrying a magnificent black hen in a basket on his back. This could be a dream, but that hen is not Prakash’s, which is white. (In one humorous scene, the boys try – and fail – to paint it black to hide its identity). Equally enigmatic is the ominous ending which seems to come out of nowhere.

If The Black Hen sometimes feels like a work in progress, it is one that is worth seeing. Min Bahadur Bham has taken us out of our comfort zone with a moving coming-of-age story filled with memorable moments of humour, pathos and tragedy. That he transports us to a world we have never previously seen, with no CGI, a very low budget and no real precedent in his country, is all to Min Bahadur Bham’s credit.

You can watch the film trailer here: