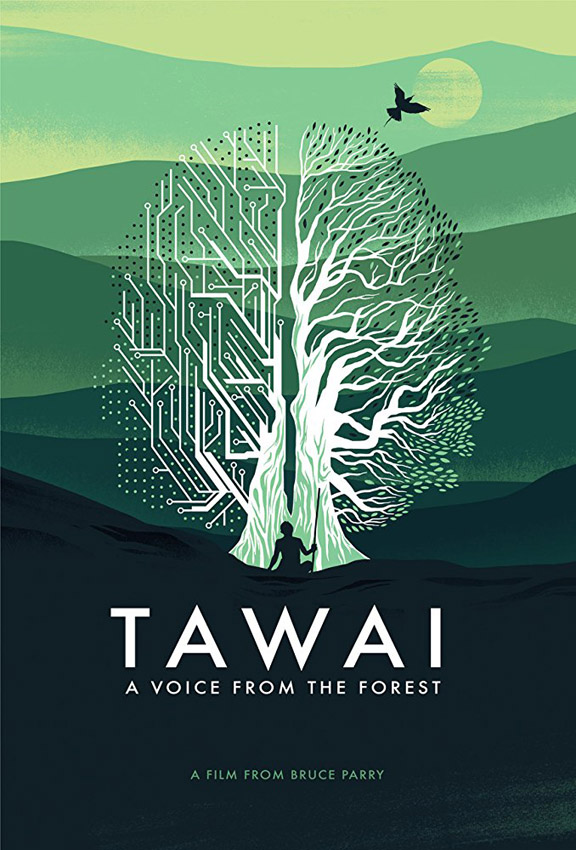

Joyce Glasser reviews Tawai: A Voice from the Forest (September 29, 2017) Cert U, 101 min.

The last time we saw indigenous rights campaigner Bruce Parry with the Penan People of Borneo was in the third series of the BBC’s Tribe in 2007. For years, Parry has been seeking out tribes on the verge of extinction and going native; amusing us with his diet of creepy–crawlies and practising lifestyles that are as foreign to us as Arnie’s trip to Mars in Total Recall. In Tawai: A Voice from the Forest, Parry returns to the Penan of Sarawak in the rainforests of Borneo, and to the Pirahã in the Amazon, with updates that result in what must surely be the most urgent and thought-provoking documentary of the year.

‘Tawai: A Voice from the Forest is a meditation on what has happened to humankind since we became separated from the natural world and began to shape it for our own unsustainable ends. There is no translation of the word Tawai in any language you might hear in the London underground. It describes a oneness with nature that ceased to exist for all but a tiny group of hunter-gathers left on the planet; tribes that, over the centuries, have left no environmental footprint.

It is the Penan People’s respect for the creatures and plants with which they share the jungle that now works against them. Because they have not left their mark on it, they have no legal claim to the land being ravaged by global industries with the support of the Malaysian government. Logging – Malaysia produces 85% of the world’s palm oil – is the main culprit; but damns, a massive oil pipeline through the jungle and land clearance for cocoa farming have all contributed to deforestation.

It is the Penan People’s respect for the creatures and plants with which they share the jungle that now works against them. Because they have not left their mark on it, they have no legal claim to the land being ravaged by global industries with the support of the Malaysian government. Logging – Malaysia produces 85% of the world’s palm oil – is the main culprit; but damns, a massive oil pipeline through the jungle and land clearance for cocoa farming have all contributed to deforestation.

The film begins with a statement that gets to the heart of the Penan world view: ‘If the really big trees die so do people. If the forest dies, so does humanity.’ For centuries the Penan and the Pirahã were hunter gatherers, owning nothing but what they carried on their backs from campsite to campsite. But now the last of the nomadic Penan and Pirahã are settling and turning to agriculture to avoid starvation as their habitat disappears.

Parry feels at home with the indigenous tribes. The danger he, and co-director Mark Ellam face is from the Malaysian government. Parry has to be smuggled across the border to begin his reunion with a group of Penan who remember him fondly.

But something has changed. They are in a transitional stage of their evolution; one not of their own choosing. Parry is taken to two long, wooden dilapidated cabins in the middle of a clearing, given to them by a charity. The cabins are next to an allotment the very creation of which has pained the tribe, as it ravishes the earth.

It is when the tribe invite Parry on a hunting and gathering expedition that we can appreciate all that is being lost. Camping out in simple, open tents (there is no desire or need for privacy) the families are in total harmony with their environment, respecting nature and one another. ‘In the fruit season’, we are told, ‘we know we won’t starve.’ One tribal member explains: ‘that is why I feel Tawai about the forest; because it will provide for me like a mother breastfeeding her child.’

‘Once the bird sings, we know the first fruit is coming,’ we are told. When the bird flies off, it is a signal for them to set off too, to gather fruit. Parry asks if they can anticipate this seasonal sign and prepare. ‘Why would we want to anticipate it?’ he is asked.

While being in tune with the environment is a necessity for the Penan, it proves to be a liability to us. We feel no qualms about destroying what we cannot see or feel in order to maintain our materialistic lifestyle. Children believe their fruit grows in Tesco’s; the jungle is an abstraction. Even the landfills and ocean sewers are remote. We build on the land, but assume it will always feed us: all 8 billion of us.

Because the tribes have, until recently, been nomadic, there has been no reason for them to store food or possessions. Many of the Penan and Pirahã still have no concept of ownership or social hierarchy (which originated with property). Sharing is at the heart of the Penan group Parry visits. They are affectionate with one another in a way that is foreign to those who talk of someone ‘violating one’s personal space.’ Is there even a word for ‘own’ or ‘mine’ in the language?

To continue his exploration of how humankind lost its way, Parry goes for a symbolic cleansing in the Ganges, joining a group of egoless wise men who are meditating before the traditional annual ceremony. Parry implores us to show empathy to preserve the planet before it is too late.

Along the way, he meets with social anthropologists Jerome and Ingrid Lewis, and psychologist Dr Iain McGilchrist, who, rather ironically, lives in blissful solitude on a stunning, private estate on the Isle of Sky. McGilchrist discusses with Parry the theory in his book The Master and His Emissary, for, rather surprisingly, the relationship between the right and left side of the brain has everything to do with how humankind has drifted away mother Earth.

Most of us have heard about the left and right hemisphere of the brain, but McGilchrist uses his research to explain how humankind has lost the plot by letting the supposedly subservient left side take over. It is the right side that sees the whole picture and the world’s interdependence. The detail-oriented left side is left to focus on a site specific task without worrying about its impact on the whole. The hemispheres, McGilchrist explains, are not thought machines with functions, but are behind an entire self-consistent version of the world. If we do not rethink our relationship with the world, that is, realign the hemispheres, humankind is doomed.

Tawai: A Voice from the Forest is playing at the following select cinemas: www.tawai.earth/screenings/

You can watch the film trailer here: