Joyce Glasser reviews Jane (November 24, 2017) Cert. 12A, 90 min.

This absorbing biographical documentary about conservationist, primatologist and anthropologist Jane Goodall is more than an inspirational feminist story. It will also get you thinking about family relationships and bringing up children and even about job recruitment. Goodall might be unknown today if her employer had insisted on a candidate having identical previous work experience and exacting qualifications.

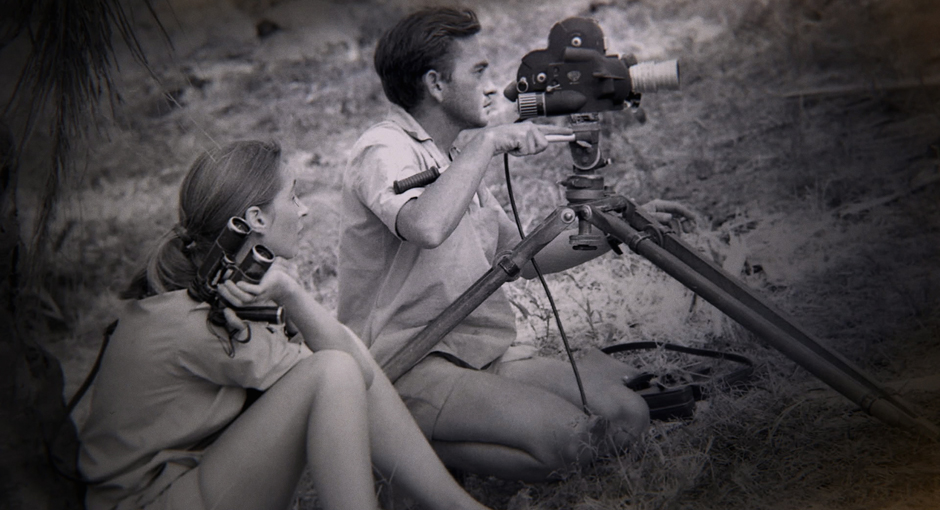

Jane covers some familiar ground, but it goes farther than any other film about her life and work thanks to some 140 hours of previously unseen 16mm colour footage – shot primarily in the 1960s by National Geographic filmmaker Hugo van Lawick (Jane’s husband from 1964-1874). The footage sheds as much light on the chimpanzees that Jane studied throughout her life as it does on her, the unlikely pioneer of research into the behaviour of chimpanzees.

Growing up around London in the 1930s, Jane dreamt of living in the jungle like Tarzan, but she was an unlikely researcher. First, because if women worked at all, it was not in a man’s job. And second, because she had no experience, no science qualifications and could not afford to go to university. She was however, brought up (her father was largely absent from her life) by an inspirational novelist mother who instilled in her a love of nature, never quashed her dreams and ‘built my self esteem.’

Growing up around London in the 1930s, Jane dreamt of living in the jungle like Tarzan, but she was an unlikely researcher. First, because if women worked at all, it was not in a man’s job. And second, because she had no experience, no science qualifications and could not afford to go to university. She was however, brought up (her father was largely absent from her life) by an inspirational novelist mother who instilled in her a love of nature, never quashed her dreams and ‘built my self esteem.’

After working as a waitress to save up for a trip to Kenya, Goodall, 23, contacted Louis Leakey, the notable Kenyan archaeologist and palaeontologist, requesting a meeting to discuss animals. Leaky was researching human evolution and believed that the study of apes could help us understand early man. He hired Jane as his secretary before sending her to Tanzania as a researcher in 1960. It was precisely Jane’s lack of bias that prompted Leakey to choose her. He wanted, Jane recalls, someone with ‘an open mind, a passion for knowledge, a love of animals and monumental patience.’

Director Brett Morgen might have been given some 140 hours of amazing, raw footage but he and several interns had to spend hours organising the footage (which came without sound, dates or notes) into a narrative. To tie it together Morgan and cinematographer Ellen Kuras (Personal Velocity) went to Tanzania to film an interview with Jane, now 83. Her ‘answers’ form the narration to her years in the Gombie Stream National Park and in the Serengeti, where Hugo spent the bulk of his filmmaking career after his contract to cover the Gombie ended.

Accompanied by her mother as a requisite guardian, Jane moved to the Olduvai Gorge and every day climbed into the hills tracking the chimpanzees ‘from dawn and until night fall…The mission was to live as close to the animals as possible,’ but patience was indeed needed. For five months the chimps ran from her and the only way she could observe them was to stand on a peak with binoculars watching them from a distance. ‘I was an intruder,’ Jane explains, [but] ‘I am not a defeatist…and I became absorbed in this ‘unparalleled period when aloneness was a way of life.’

She was also either brave or naïve. Sleeping out overnight and stepping around poisonous snakes in shorts and sandals, if she was fearless, it was because she respected her environment – and because no one had told her to be afraid.

The first breakthrough came when, one day, David Greybeard, her name for the patriarch of the community, did not run away. Soon the others followed his example. It was then that she observed a chimp using a ‘tool’ – a branch was scraped of leaves – to penetrate holes and extract insects. This observation, which she telegraphed to Leakey, made headlines around the world as it meant that scientists had to re-evaluate the definition of man, or extend it to primates.

The publicity then, as now, was a two-edged sword. Jane looks back on the headlines which highlighted her good looks and great legs rather than her accomplishments. ‘It was so stupid – it didn’t bother me. It was really very useful because by this time I was needing to raise money myself so I made use of it.’

Jane’s fairy tale story also has a prince charming (technically, Hugo is the son of a baron, a fighter pilot killed in WWII). In 1962 Jane feared that her life would be compromised when the headlines result in a grant from National Geographic. With that came chain smoking wildlife photographer and filmmaker Hugo van Lawick. ‘It was obvious to me right from the start that I was a subject of interest as well as the chimps,’ Jane confides, and in 1964 they married in London before returning as a team (Jane would write books and Hugo would make films) to the Gombe.

After the chimps accepted her presence in their camps, she initially welcomes their first visit to her campsite for bananas. Jane soon learns that primates are ‘unconscionable thieves’ as they invaded the campsite, stealing anything they could chew on. And much later, after the death of Flo, the community’s matriarch, Jane observes the chimpanzee community she thought that she knew so well divide and wage war against one another. We also observe a devastating polio epidemic which led to researchers being prohibited from touching the animals

Morgen integrates the footage showing three generations of the chimp family – focusing on matron Flo, daughter Fifi and son Flint with Jane’s experience of becoming a mother in 1967. This narrative is both charming and heart-breaking as we follow the fate of Jane’s marriage and Flo’s life. For Jane, Flo was the perfect mother to the adorable Flint. But Flint remained – fatally – a mama’s boy and never developed into a normal adolescent chimpanzee. Jane was luckier with their beautiful son, ‘Grub’ although work always took precedent. Grub, who hated chimpanzees, was sent to school in England and then worked with his father.

With students running the research station in the Gombie, Jane tells us that from 1986 her life changed. She has not been in one place for more than three weeks due to fund-raising for her conservation charities. What she does not mention is that in 1985 her contemporary and fellow Leakey protégé Dian Fossey was murdered in her Gorilla research station. The killer – a suspected animal trader or native poachers – has never been caught. In fact, there is no mention of the ‘Gorillas in the Mist’ author or of the two women’s friendship. What there is, however, is wondrous footage and food for thought.

You can watch the film trailer here: