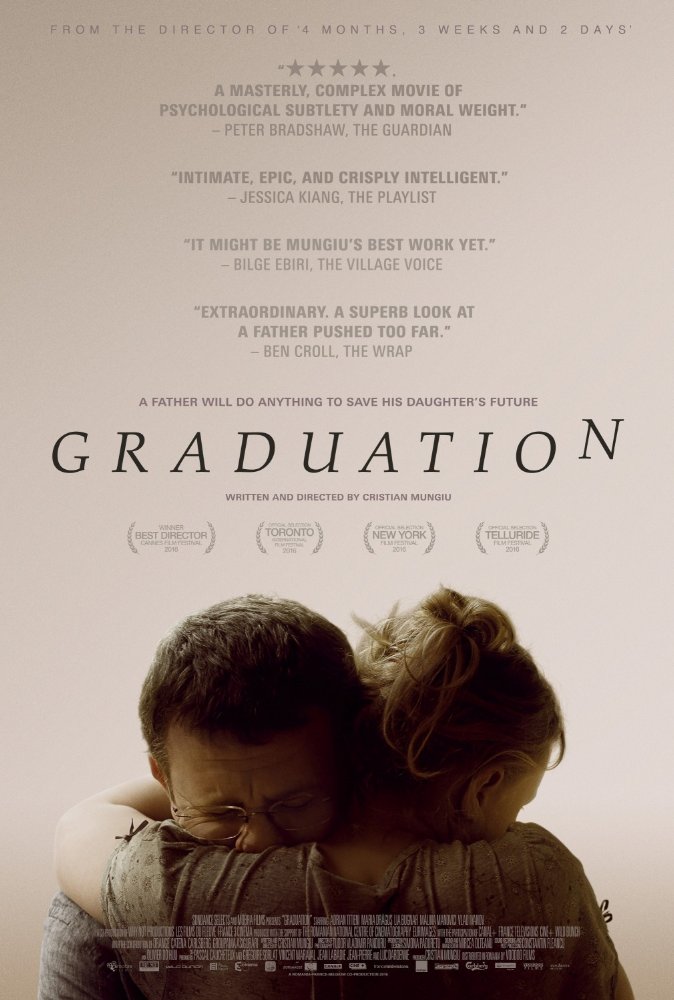

Joyce Glasser reviews Graduation (March 31, 2017)

One of the reasons that Christian Mungiu is such a deservedly acclaimed writer/director is his ability to incorporate controversial contemporary issues into a fictional story without preaching, moralising or sending an explicit message. And when your films are about women struggling with the consequences of a tradition of sexual repression, dogmatic faith, dictatorship and ignorance, as in 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, and Beyond the Hills, it’s tempting to send messages.

In Graduation, a potent and excruciating study of disillusionment in an idealistic family, Mungiu gives in to this temptation. Graduation is nevertheless a worthwhile plunge into the moral quagmire of Communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu’s legacy as a father compromises his principles to help his daughter achieve a better life.

The Aldea’s live in a small, comfortable apartment in a depressing housing estate that has been left to atrophy like the hopes of its inhabitants. Mungiu’s camera lingers on every corner of the run-down estate as though he wants us to imagine we live there or understand those who do.

The Aldea’s live in a small, comfortable apartment in a depressing housing estate that has been left to atrophy like the hopes of its inhabitants. Mungiu’s camera lingers on every corner of the run-down estate as though he wants us to imagine we live there or understand those who do.

Dr Romeo Aldea (Adrian Titieni) and his chain-smoking wife Magda (Lia Bugnar), an attractive, permanently lethargic woman who has let herself go were part of the liberal, intellectual vanguard that left Romania under Communism. They returned in 1991, three years after Ceaucescu’s execution, to prosper in the country’s newfound freedom and contribute to its progress. What they discovered, however, was corruption, small-mindedness and stifling bureaucracy. They have regretted the return ever since.

If Romeo cannot save his country or his marriage, he is determined to save his intelligent, pretty daughter Eliza (Maria Drăguş) who is off to school to prepare for final exams the following day. Eliza has a scholarship to a top UK university, which, to Romeo, is tantamount to a passport to success, security and happiness. At all costs, she must escape Romania before she, too is sucked into its deadening quicksand. Despite being a commended surgeon, Romeo’s feels his life is a failure. Through Eliza his ideals and hopes can live on and find fruition.

Romeo, solicitous to a fault, drives his daughter to school, and after dropping her off drives away. The next time he sees her, Eliza is in bad shape. She has been assaulted by a rapist and traumatised. Although she fought him off, in the struggle, her arm was broken and is now in a sling. It is her right hand, and Eliza is worried that she will not be able to write fast enough to complete the exam the following day.

Romeo’s life as a doctor is busy enough, but as his name (as opposed to his stodgy, plain looks) suggests, he has managed to seduce Sandra (Mălina Manovici), an attractive, young school teacher and single mother whose son needs special care. Sandra and Romeo have genuine feelings for one another, but – because of her son’s condition – Sandra needs a favour of Romeo in a dysfunctional society where favours are the only way to get anywhere or get anything done.

And it is into this bottomless pit of favours and bribes that the principled doctor falls when Eliza’s scholarship is put in jeopardy by the prospect of anything less than a top score. What Romeo does not realise is that Eliza has a handsome boyfriend who is teaching her to ride a motorcycle. She wants to attend university and have a career, but might not share Romeo’s conviction that her only chance of happiness lies abroad.

The dialogue throughout the string-pulling scenes is impressively woolly and inferential, with everyone from the Police Chief, Ivanov, to the Vice Mayor, Bulai, assuring everyone else that they never resort to bribes while doing just that. There is an aura of paranoia, and a subtle, but occasionally more forceful, distancing of the parties once the deed is agreed, just as gang members go their separate ways after the heist.

Romeo’s life becomes consumed by his illicit activity, but he keeps the end goal in sight to maintain his sanity – and his conscience. For one of the reasons he left under the Communist regime was to avoid the very stagnant bureaucracy and unprincipled, desperate society to which he is now contributing.

There is, however, a problem more onerous than Romeo’s conscience or his fear of being arrested for it is beyond his control. The plan that Bulai proposes requires Eliza to put a specific mark on her anonymous exam paper…

The performances are, as in all of Mungiu’s films, extraordinary, and he creates a sense of place – stifling, tense and paranoid – that we inhabit with the characters for the duration of the film. Yet, at two hours, the continual meetings and conversations – all revolving around the central moral issue and exam – grow repetitive. In this country, we are aware of the lengths that parents go to ensure that their children get into the top schools, and get the best start in life, so UK audiences will appreciate Romeo’s dilemma. But Magda’s emergence at the end of the film as the moral compass tends to depreciate the debate that might have sent audiences out to dinner to argue Romeo’s case.

You can watch the film trailer here: