Joyce Glasser reviews Free Solo (December 14, 2018), Cert. 12A, 99 min.

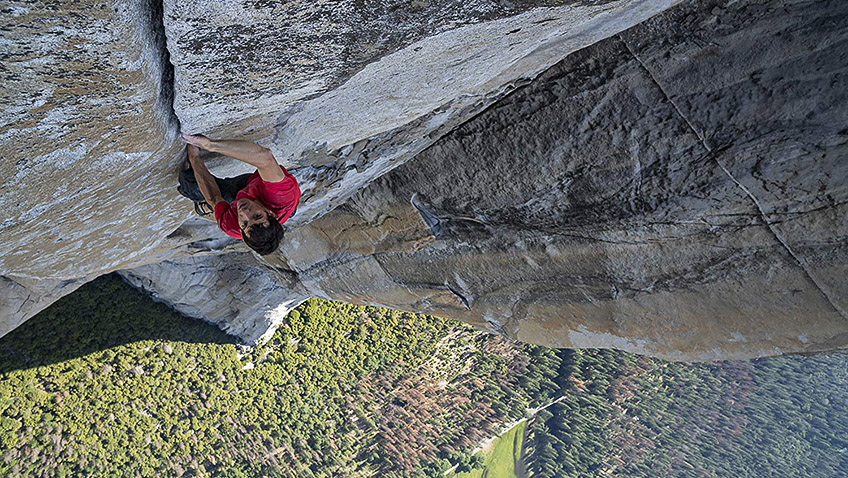

If, like Alex Honnold, an MRI should reveal that your amygdale, the fear centre of the brain, is inactive, your experience watching Free Solo, directed by Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin, might be different from the rest of us. The film captures Alex’s attempt to climb the sheer granite face of Yosemite’s El Capitan free solo – without rope or other equipment. El Cap as it is affectionately, or respectfully, called, has ended the lives of free soloists and climbers with rope, but Alex, in 2017, set out to become the first free solo climber to scale the rock at its highest point. If your amygdala is normal, expect sweaty palms and don’t be surprised if, like cameraman Mikey Schaefer, with his long-lens camera safely on the ground, you find yourself looking away or closing your eyes. The high-tech cinematography is spectacular, but the responsibility of filming a friend’s death comes under discussion in this thought-provoking and, frankly, awesome documentary.

And death is on everybody’s mind when Alex, a good-looking, modest 32-year-old is preparing for the challenge that he has put off for almost nine years. That is the number of years he has been living out of his cramped van, although, as he tells a group of school children, he earns about as much as a well-off dentist from sponsorship deals. His travels – to Zion National Park’s Moonlight Buttress and the slippery limestone cliffs of Taghia, Morrocco – are all work related, so there is no need for a wardrobe other than climbing shoes, chalk and a bright coloured t-shirt if anyone is watching.

Chances are, if you are Alex Honnold, someone will be. He is not only one of top ranking climbers in the world, on the cover of countless magazines, but as veteran climber Tommy Caldwell reflects, probably the only known free soloist left alive. Half-way through the film Caldwell makes the comment and we see a short montage of the super-fit daredevils who have perished, including Derek Hersey, who died on Sentinel Rock in Yosemite National Park; fitness fanatic John Bachar and Sean Leary, who in 2009 recorded the speed record of the Salathé route on El Capitan (in 4:55 hours) with Alex.

Caldwell has climbed El Cap many times, but would never do it without a rope, which is challenging enough. “Imagine an Olympic gold medal-level achievement where if you don’t get that gold medal, you’re going to die,” Tommy Caldwell postulates. It’s not a matter of disappointing your family and sponsors and trying again in four years, if possible; if you put one foot or finger in the wrong place or encounter an unexpected slippery patch, you are guaranteed a quick death.

But in the spring of 2017 Alex begins his methodical preparation for climbing the rock’s highest (3200 feet) point using the challenging Freerider route. Where most people see smooth granite surfaces that only Spider-Man could scale, Alex looks for tiny ledges for his feet and crevices for his chalked fingers to grip onto. Alex asks Tommy to join him on his preparatory rope climbs, and the crew is on hand to capture the activity.

Alex does not like to talk about his readiness for the ascent as it puts added pressure on him, and so the crew hang around and try not to act disappointed when he bails out after beginning the climb in the summer. The crew’s main task is to keep out of his way, but, though drones are used, we cannot forget the danger facing the cameramen dangling from ropes with camera equipment.

The documentary briefly covers Alex’s childhood when his mother (who appears briefly in the film telling us it is pointless trying to stand in his way) took him to his first climbing session in a gym aged 5. In no time, he had climbed 30 feet and was hooked. He dropped out of UC Berkley where he was to study electrical engineering, and, after his parents’ divorce, he sought refuge in the rocks. He is the holder of many records for height and speed and free soloing, chronicled in his memoir, Alone on the Wall, but the El Cap remained elusive.

As well as covering his childhood, the documentary explores his relationship with the pretty, athletic climber Sanni McCandless. Since meeting Sanni, Alex suffered two accidents, one when he fell and broke his ankle, although he cannot remember how. You can imagine how Sanni feels when Alex tells the directors, ‘I’ll always put climbing before a girlfriend,’ but you can also imagine that this confession would come as no surprise to anyone sharing a cramped van with Alex.

‘Nothing is ever accomplished by being happy and cosy’ Alex muses, which philosophy might be another challenge for this good natured, smiling Sanni. She does manage to convince him to buy a house near Las Vegas but the cosiness factor is less important than the location – in climbing country. The house is an investment and perhaps a place for Sanni to wait for Alex sleeps alone on the night before a climb. As she drives away from his van, her eyes fill with tears at the very real thought that she will never see Alex again.

Since we might suspect that the ending is a happy one, there is less suspense than there was for Sanni, but it is still an experience which anyone who suffers from height sickness will find daunting enough. We are with Alex when he faces, for the first time without a rope, the Boulder Problem. This is an exposed point where he has to stretch his leg into a karate kick across to a tiny ledge and then reach for a handle for his hands to swing the other leg around. ‘Of course I look down’, Alex says in an interview for the film, but you can only hope he was not looking down at the clear 2,000 foot drop at that moment. Once he is through the Boulder Problem a big smile emerges and he seems to scramble up the rest of the rock (he reached the summit in less than 4 hours) like his 5-year-old self in a climbing gym

The film grapples with the morality of profiting from filming or using in advertising someone’s death defying stunts. Some sponsors have cancelled sponsorships of extreme sport obsessives for fear of being seen to encourage reckless challenges, but so far Alex is lucky and earns enough to allow him to focus entirely on climbing. But in a sport where the likelihood of death is almost as high as the certainty of death should an error occur, the odds are not in Alex’s favour.