Joyce Glasser reviews Apollo 11 (28 June 2019), Cert. U, 93 min.

It might be the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing, but for 93 minutes in the cinema you can roll back the years and book yourself a place in the launch crowd; in the control rooms in Miami and Houston; in the space capsule; on the moon and in the Columbia as it splashes into six foot swells in the Pacific Ocean as Navy helicopters lift the astronauts to the deck of the SS Hornet. All you have to do is find the largest possible screen on which to get the most from Todd Douglas Miller’s Apollo 11: a technological marvel full of emotion and awe.

The making of Apollo 11

would be a fascinating film in its own right. The documentary distinguishes itself by having no narrator, no talking heads and no original footage or interviews. Everything you need to know is either on the screen in captions similar to those on a computer screen, or in existing, contemporaneous commentary. There is, in short, nothing separating you from a ‘live action’ journey: from the crowds gathering before dawn on 16 July 1969 around Merritt Island, Florida to watch the launch until the August 13 parades in New York and Chicago.

Making a documentary from archival footage might sound easy, but, on the contrary, Miller and his team have done a service to his country, and to the world, in preserving and making public raw footage that had been all but forgotten. Apollo 11 is a ground-breaking and painstaking cinematic achievement and a fitting tribute to the space mission that not only gave credence to the slain President John Kennedy’s 1961 prophetic declaration, but united the world in awe eight years later.

Kennedy was more interested in winning the Cold War than in the very costly space programme itself. But he gave good oratory and hearing, as we do in the film, his rousing 1961 speech initiating the lunar programme with a step-by-step description of what would happen, it is hard to believe it was not written after the fact.

Miller’s 2014 riveting documentary Dinosaur 13 might suggest that he has a thing for titles with uneven numbers and stories of monumental time-travelling discoveries. But if 13 proved to be an unlucky number for the hapless team of palaeontologists and researchers in the South Dakota Bad Lands, 11 proved the luckiest of numbers for three astronauts and an entire nation racing against the clock to beat the Soviets’ much more active and advanced space programme.

NASA had in fact been thinking ahead to the film medium while the astronauts were in training. Thanks to Theo Kamecke’s 1972 film Moonwalk One, commissioned by NASA, but hardly shown, the NARA (National Archives and Records Administration) had a vault of unseen reels of Todd-A0 widescreen footage of the first moon mission left over in its vaults. NASA itself also shot footage of the mission although the reason it did so is unclear. And, surprisingly, their footage was shot in the same format that Joseph L. Mankiewicz used to shoot Cleopatra.

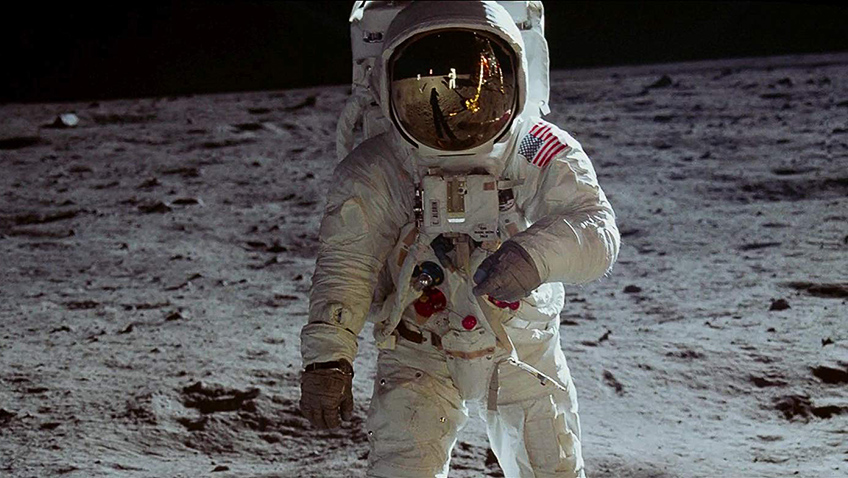

NASA recognised that if Miller would assume the financial burden of digitising all that 70mm footage it would be preserved and could be more widely available. It is the combination of this 70mm archival footage transferred into high-definition digitised images that produce that feeling of awe and immediacy. We even have a fly-on-the-wall glimpse into the suiting up chamber where the no-doubt nervous astronauts, deep in concentration are focussed on every detail of their attire for the next 8 days.

The high definition widescreen images not only heighten the colours, but produce a scope and clarity that allow historians, scientists, space nerds and ordinary viewers to notice a lot more than when the images were cropped. While it is a treat for all ages to see the spectators’ period clothing, hair styles, cameras and cars as they congregate on the beaches and in the car park of JC Penny, sharp-eyed viewers can now make out America’s number one talk show host, Johnny Carson, and the science fiction writer Isaac Asimov in the VIP area. You can see a reflection of the rocket launch in a pair of sunglasses, while on the deck of the Navy’s SS Hornet you can perceive President Nixon. We hear the historic phone call from the White House to the astronauts on the moon from the man who would, in 1974, resign in disgrace.

While the world was fixated on the moon, a radio we hear from time to time reminds us that America was embroiled in the Vietnam War and distracted when, two days after the launch, 37-year-old Senator Ted Kennedy, drove his car drove off a bridge in Chappaquiddick, killing his 28-year-old companion, Mary Jo Kopechne.

Miller’s other unexpected discovery was a cache of more than 11,000 hours of audio recordings. While Miller and his team knew that audio tracks existed, these unknown recordings were made by two custom recorders that captured individual tracks from 60 key mission personnel throughout the mission. But it would be another matter to undertake the laborious and meticulous task of synchronising those tracks with the video. This was accomplished by Stephen Slater, a space fanatic from Derbyshire, UK! Thanks to Slater, on the film we can see individually named mission controllers talk to and even joke with the astronauts in space.

Equally wonderful is Matt Morton’s atmospheric, pun intended, original music, made with a 1968 Moog synthesizer and period instruments, which turns romantic as the Eagle launches off the lunar surface and floats towards Michael Collins in the Columbia Command Module that had been orbiting around the moon. Miller and Morton also make use of the astronauts’ compact Sony TC-50 cassette recorders on which they stored mix tapes, assembled by Mickey Kapp (now 88) working for his father’s record store near the Space Centre. One such track on Neil Armstrong’s recorder was the newly released Mother Country by Johnny Cash sound-alike John Stewart. The moment when Morton enhances the sound against a montage of the celebrating astronauts reunited in space and controllers on earth is a tear-inducing emotional high.

You can watch the film trailer here: