Joyce Glasser reviews A Beautiful Day in the Neighbourhood (January 31, 2020), Cert. PG, 108 min.

It’s perfect casting: Tom Hanks, an actor who is so nice, so wholesome, and so uncontroversial that you’d trust your young children with him. Who else could play Fred Rogers, that saintly, compulsively empathetic, caring and utterly sincere man who, from 1968 to 2001 (he died in 2003) masterminded and starred in the idiosyncratic, instructive children’s programme Mister Roger’s Neighborhood, recreated in the movie. And the subject is a perfect match for the talented director Marielle Heller, who explored the psychological complexity of another needy, disturbed writer in the excellent Can You Ever Forgive Me? Despite Hanks’ star billing and his amazing transformation into Rogers, his character is not the angst-ridden writer, but the healer. One problem with Marielle Heller’s A Beautiful Day in the Neighbourhood is that it is a double biopic, based less on Rogers than on the journalist Tom Junod, whose article, ‘Can You Say …Hero?’ inspired and informed scriptwriters Micah Fitzerman-Blue and Noah Harpster.

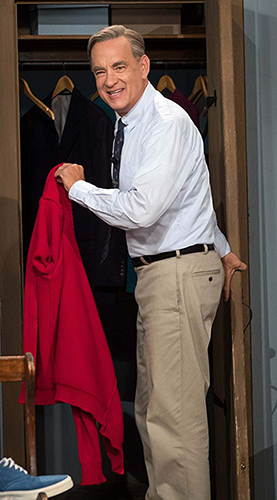

The child-friendly set of the show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood is recreated so faithfully that adults who grew up with Rogers will feel a surge of nostalgia while others will welcome the time warp. In a sound-studio in Pittsburgh, 1998, Rogers walks through a Sesame Street like door, and down a set of steps into a wooden house where he changes into something comfortable taken from a closet behind his chair, while singing the programme theme song. Then, for the lesson of the day, Rogers begins to talk about his new friend Lloyd Vogel (Matthew Rhys), uncovering from a photo board, Lloyd’s photo, complete with a bruised nose.

In his soothing voice, the all-American Rogers confronts the audience, and tells us that ‘someone has hurt my friend, and not just on his face. He’s having a hard time forgiving the person.’ After explaining to the children what forgiving is, he says, ‘It’s strange, sometimes it’s hardest to forgive the people we love.’

We then meet Lloyd Vogel, cleverly, before he has met Rogers and before the bruised nose. Returning from a dinner where he has won the National Magazine Writer of the Year award, Lloyd greets his wife Andrea (Susan Kelechi Watson), a public interest attorney, who is talking about packing nappies for their new baby. They are going to a wedding, to which, she breaks the news, Lloyd’s estranged father Jerry (Chris Cooper) has been invited. We can tell he is upset at this news because he cannot install the baby seat that Andrea easily secures in the car.

Behind Lloyd Vogel’s cynical, ambitious, dismissive and angry persona is a vulnerable boy who could not protect his dying mother when his two-timing, father, Jerry, abandoned them. Now Jerry, with a new, long-term partner and an historic penchant for alcohol, makes the mistake of calling Andrea, “doll” and a physical fight ensues, resulting in the bruised nose we have seen in the photo.

When Lloyd’s editor assigns him an interview with Mister Rogers, he is furious. His editor tells Lloyd that Rogers was the only person who was willing to be interviewed by him. When Lloyd protests that everyone wants an interview with him, she confides, ‘yeah, until they’ve read what you wrote about them.’

Though we never really learn this in the film, Rogers is a brilliant academic, who excelled in music (hence the live singing and later, a piano duet on matching grand pianos with his wife). He also attended Pittsburgh Graduate School of Child Development where the insights he gained fed into his programme and helped him formulate an approach – using puppets, singing and guests – to teach children about death, divorce, sibling rivalry, bullying, and even money matters.

Tom Hanks in A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood

Lloyd, naturally, believes it must be an act to do some good while making money on WQED. He goes into the interview as a journalist normally would, to direct the interview with an aim of getting his subject to reveal his true self. Rogers pre-empts the interview by asking Lloyd about himself, and cunningly drags it out, obliging Lloyd to return. The conceit of the film is that Rogers, knowing a child in an adult body when he sees one, turns the tables on the Esquire reporter. ‘We are trying to give children positive ways of dealing with their feelings’, he tells Lloyd, setting out the approach he will use on Lloyd himself. He will even pay a visit to Lloyd’s family regardless of the embarrassment it might cause. But this crusade begs the question: what does Rogers have to hide that he is so skilled at avoiding Lloyd’s questions?

Rogers has an annoying way of turning questions back at the interlocuter. When Lloyd points out that people lining up to tell him their problems must be a burden on him, Rogers replies, ‘I’m grateful for your compassion, Lloyd.’ Uttered by a mere mortal, this patronising and sarcastic response would be offensive, but Lloyd can only marvel to what extent the real man is identical to the beloved television guru.

Soon Lloyd makes a point of rushing back to Pittsburgh (even when Jerry is in hospital with a stroke) because Roger’s subtle therapy is already working. By the time Rogers asks him why he is fighting with his father, deep, buried truths emerge.

While some viewers might find this interaction charming and touching, and Lloyd’s transformation miraculous, others might balk at Rogers’ manipulation of a weak, vulnerable man who was commissioned to get a story about Rogers, but failed.

At one point we think we may finally be getting somewhere. Lloyd hits a sensitive point when he invites Rogers to tell him about his own relationship with his two sons. ‘It couldn’t have been easy to have a father like you.’ Rogers tries to deflect the wound by thanking Lloyd ‘for that perspective’, but at last we have a clue that Mr Perfect rubbed his eldest son the wrong way. We learn nothing about his wife.

While the filmmakers use Tom Junod’s confessional story to fashion what for some might be a tear-jerking climax and happy family denouement, there is no avoiding the word sentimental. But the filmmakers omit the role of religion in Rogers approach and you might feel the omission. Rogers changed his plans to enter a seminary after university when he envisioned the power of television to “nurture” more wounded souls than he ever could behind a pulpit. The religious angle is so low key as to be all but absent, but it is critical. Rogers is a cult leader. Vogel’s experience was positive, but neither Vogel nor the audience ever get inside the titular character.

You can watch the film trailer here: