Joyce Glasser reviews The Good Boss (July 15, 2022) Cert. 15, 115 mins.

The abundant irony is as unsubtle as co-producer, writer-director Fernando Leon de Aaranoa’s commentary on Spain’s shifting demographics and social structures in The Good Boss (El Buen Patron).

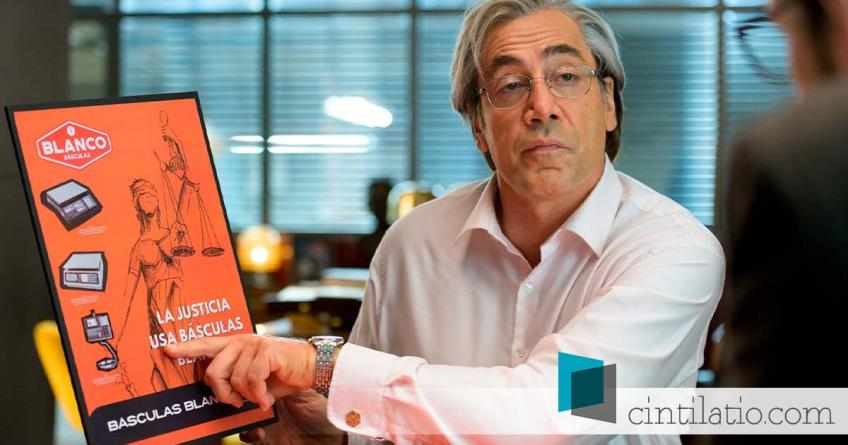

Though more artful than Seth Gordon’s Bad Boss films, the heavy handed nature of the problems facing Javier Bardem’s eponymous medium-size factory grow tiresome. Not so Bardem’s terrific performance as his grey-haired character resorts to political connections, pleas, manipulation, deceit, lies and even blackmail to win a prestigious award for Básculas Blanco, the factory making industrial scales that he inherited from his father.

That The Good Boss is a dark comedy about how Spain’s changing demographics (and human rights laws) affect the workplace, it opens on an unpleasant racist mugging in a park where one of the minor, characters is introduced as he gets hauled off to jail. The culprit’s father is Fortuna (Celso Bugallo), who is sorting out the Blancos’ pool pump as they breakfast in their pretty garden. Fortuna’s plea for his boss’s intervention results in the son getting a temporary delivery job for Julio’s wife’s Adela’s (Sonia Almarcha) high-end dress shop.

If the son’s presence scares off Adela’s customers, it’s a price worth paying, at least until an all-important inspection by a Committee handing out a prize for business excellence has taken place. Blanco’s attention to detail extends to a symbolic set of scales at the entrance to the factory that is off kilter. He orders his disloyal security guard Román (Fernando Albizu) to get it fixed. Since the problem with the scales is symbolic, it never is repaired.

Blanco likes to present himself as the magnanimous head of a family, referring to his staff as his children. ‘Goodbyes are really tough,’ Blanco tells a crowd at a “family” meeting. ‘Those who knew my father know he was a just man. That’s why he made scales, ’Blanco says in a non-sequitur bit of reasoning you know he has used before. Blanco presents the “goodbyes” – his euphemism for layoffs – as “part of life’s processes,” reminding the employees that ‘we taught you everything we know and that’s a lot.’

If the factory is a family, then incest is rife, as a bit of foreshadowing suggests. As Blanco calls forward a sacrificial young woman named Victoria for her “goodbye”, she blurts out, ‘I love you’ before running off. Later, when Blanco flirts with a tall, pretty and seductive marketing intern, Lilianna (Almudena Amor) and then attempts to get rid of her, we wonder whether Victoria wasn’t part of a pattern.

Then there is head of production Miralles (Manolo Solo) who has slept with Blanco’s secretary Inés (Yael Belicha) but is distraught over family problems. He is distracted and causing problems at work because his wife, Aurora (Mara Guil) is having an affair with Miralles’ Muslim rival Khaled (Tarik Rmili), and she wants a separation.

Blanco initially uses the carrot with Miralles, a childhood friend, inviting him to dinner and giving him time off work. When Miralles proves inconsolable and his absence stops the production line, Blanco has to use the stick.

His appeals to Aurora backfire when he tries to justify his interference by telling her that her marital problems have become problems for the company. When Blanco tries the same approach with Khaled, he is told where to go. Khaled is ambitious but proud, too, and he knows that Blanco needs him in more ways than one.

Blanco’s most immediate problem, however, is civil disobedience when sacked employee José (Oscar de la Fuente) sets up a messy protest camp on public land directly across from the factory. He uses his two little daughters for their emotional value in press articles and local televised news. The Inspection Committee must not see the banners and hear José’s rants through the bull horn.

A disingenuous call to the police also backfires when the police point out there is nothing they can do as the nuisance is on the public land the girls are not, as Blanco has suggested, being trafficked or abused. Like the security guard, the police are on José’s side in what is becoming a class dispute.

Beginning with the title, and Blanco’s name, which means “white,” suggesting purity and goodness, the irony declares itself. As the grievances, romantic entanglements and ambitions of the outspoken employees challenge Blanco’s ability to resolve them, we see the way the film is going and there’s not much suspense.

Nor is there much sympathy for any of the broadly drawn characters and predicaments. The characters are like symbols, representing various challenges a contemporary EU boss has to deal with. Blanco learns the hard way that young women are not all as compliant as Victoria. Blanco’s wife is no pushover either and her curious decisions to offer Liliana a sexy dress from her shop and invite this attractive, single woman to live in their home, suggest she is wise to her husband and might be out to punish him.

But Blanco is such a power wielding, hypocritical narcissist it is impossible to root for him either. Nothing he does is altruistic and his regard for the wellbeing of his staff is as phoney as the loyalty he believes they owe him. This might be a social satire, but it leaves us so disgusted with all the characters that is difficult to engage in the outcome.