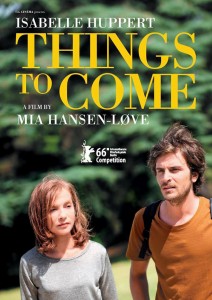

Joyce Glasser reviews Things to Come (September 2, 2016)

Actresses over 60 rightfully complain about a lack of meaty roles, but not Isabelle Huppert, one of the world’s greatest, and busiest, actresses. In Mia Hansen-Løve’s Things to Come Huppert turns Nathalie Chazeaux, a spirited, caring, multi-tasking, mother and 60-something philosophy professor, into a person we can all identify with as her life begins to fall apart.

In French, the film is called L’Avenir (The Future). This is an intriguing title for a film about a woman whose life is withdrawing, but one that that reflects the newfound freedom that accompanies the loss of a lifetime of responsibilities.

In French, the film is called L’Avenir (The Future). This is an intriguing title for a film about a woman whose life is withdrawing, but one that that reflects the newfound freedom that accompanies the loss of a lifetime of responsibilities.

A student herself during the 1968 revolution, this time Nathalie is not joining the students striking over changes to the retirement age. Instead, she is lecturing on Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, a story of passion and renunciation, with faint parallels to Nathalie’s. ‘As long as one desires, one can do without happiness,’ she suggests to the class, before she herself is tested.

Hansen-Løve admits that the story is based loosely on her own mother who separated from her philosopher-husband late in life. The details are so particular and the emotions so astutely captured that we are dropped into what seem like real lives. True to the intellectual inclination of parents who are both philosophy professors, the film opens with a family, who have a rustic cottage on the sea in Brittany, visiting the tomb of Chateaubriand, best known for his autobiographical, Memories from Beyond the Grave.

The visit to the grave and references to death and memory (reminiscent of Hansen- Løve’s The Father of My Children) is squarely in front of us, as is the tie to Rousseau (whose Confessions served as a model for ‘Memoires’). Though the story develops in a gently meandering style, there is nothing random about this, or any scene in the film.

Like The Father of My Children, we first meet a woman who seems to have it all, including a secure, loving future. Not long into the film, however, Nathalie begins to feel the pain of loss, a pain that will continue until she finds herself again. It’s natural that her two children fly the nest and that her flamboyant, possessive mother (Edith Scob, superb), a needy, prima donna, passes on with Alzheimer’s. But Nathalie is shocked when her husband of 25 years announces he is leaving her for another woman. Never short of words, Nathalie can only murmur: ‘I thought you would love me forever.’ No one but Huppert can make these familiar words seem so fresh and heart-rendering.

Nathalie and her husband make a trip back to their cottage in Brittany to pack it up for sale following the separation. While her husband urges her to keep the cottage, Nathalie rejects the offer, reproaching him for not recognising it holds too many memories. This where we brought up the children, she reminds him, exposing her pain. But Huppert doesn’t do melodrama.

When she receives an urgent call from Paris about her dying mother (right to the end, these calls come at the worst possible moments) and finds there is no signal in the house, she rushes out to the beach, trying to find one. Stumbling over the pebbles and sinking into the sand, while fighting with the phone for a voice on the other end, Nathalie’s anguish becomes comical – a feat that only an actress of Huppert’s calibre can pull off.

While her personal life is crumbling, Natalie hangs onto the profession she loves, Outside the school, however, her professional standing is eroding, too. Young whippersnappers decide against publishing her book and a handsome, former prize student, Fabian (Roman Kolinka), has outgrown his mentor. Nathalie, who has not seen Fabian in a while, is impressed with his scholarly development, but is somewhat shaken that he is not agreeing with her opinions any longer.

Nathalie nonetheless finds herself clinging to Fabian, but, the oldest person to visit the communal retreat he shares with his girlfriend near Grenoble, she finds herself out of place and alone with her mother’s cat. If the cat is now free of its protective owner, Nathalie is now free of her responsibilities as a mother, daughter and wife. The freedom which she should be welcoming, however, is proving difficult to embrace.

When Fabien suggests giving the unloved cat away, Nathalie reflects: ‘To Whom? No one wants an old black cat, obese, to boot.’ Just as Nathalie could not ignore her mother’s disruptive late night calls, so she finds herself caring about a cat she always detested. When the cat, which has never been outside alone, wanders off, Nathalie fears that ‘she won’t survive,’ – no doubt a subconscious expression of her own fear of things to come. Fabien reassures her with the word: ‘instinct.’