Joyce Glasser reviews The Confession: Living the War on Terror (August 12, 2016)

In addition to some archival footage, a few fairly innocuous comments from a couple of ‘experts’ and a defensive comment from the subject’s father, The Confession: Living the War on Terror, is, almost entirely comprised of one talking head. This talking head, is however, that of one of the most controversial, high-profile British Muslims in the history of the War on Terror.

Moazzam Begg is a handsome, articulate and dignified British Pakistani Muslim, born and educated in the UK. He is the son of a retired bank manager from Birmingham who is given just enough screen time to assure us that his son is incapable of breaking the law or engaging in violence. The film adds little to Begg’s autobiography where he calls himself a ‘war tourist’. But it is less what Begg does say than what he does not, and is not asked about, that is the major problem with this film.

The production notes state that, ‘His story gives a unique insight into three key strands of British experience: the origins of global jihad and its moral decline into terrorism; the decision of British governments to sacrifice some of their core values to fight it; and the disintegration of multiculturalism in the face of a supposedly generational conflict between the West and Islam.

Curiously, though, insights are not in abundance, nor are names. Begg’s focus is narrow and selective. He tells us that, deeply affected by the ethnic cleansing of Muslins in Bosnia that the UN troops were doing nothing to stop, he travelled to Bosnia, inspired by the mujahedeen. He fought briefly before realising that military life wasn’t for him. This particular humanistic act could be compared to George Orwell’s decision of conscience to fight in the Spanish Civil War.

What followed is murkier. The Bosnian experience began a life of donating money to various jihads, but not participating in them. And a life of living in training camps – even in the White Mountains of Eastern Afghanistan where the Donald Rumsfeld was searching for Osama Bin Laden – but not taking part in training. And of hanging out with criminals who are indicted while he cannot be for lack of evidence.

What followed is murkier. The Bosnian experience began a life of donating money to various jihads, but not participating in them. And a life of living in training camps – even in the White Mountains of Eastern Afghanistan where the Donald Rumsfeld was searching for Osama Bin Laden – but not taking part in training. And of hanging out with criminals who are indicted while he cannot be for lack of evidence.

Begg says little of the reasons for which the USA detained him under suspicion of terrorism in Pakistan, Afghanistan (Bagram Prison, where he claims to have been tortured), Cuba (Guantanamo Bay, where he was not physically tortured) and Britain (Belmarsh) other than to mock them. He points out that the UK’s and USA’s lack of knowledge of his culture and the West’s prejudice against Muslims are major hindrances in their war on terror. Few could argue with that.

Each time, the charges were dropped for lack of evidence. That said, Begg’s Wikipedia pages mention that ‘in 1999, Butt began a five-year prison sentence in Yemen for planning a terrorist bombing’, but this is not mentioned in the film.

Begg is also accused of hanging out with a Who’s Who of international terrorist leaders, but in the films, names are few and far between. Not mentioned in the film, Begg was charged with attempting to defraud the Department of Social Security. The charges against him were dropped, but a friend of his, Syed Murad Meah Butt, pleaded guilty and served time in prison.

In 1998, Begg opened an Islamic book and video store in Birmingham where he denies on camera selling incendiary literature. He does not comment on the Wikipedia claims that in 1999, Begg, through the book store, he commissioned and published a book by Dhiren Barot (using a pseudonym) referred to as bin Laden’s “UK General” and convicted of terrorism offences in the UK.

Begg mentions a raid on his bookshop, but not the fact that a former employee was an illegal immigrant from Algeria who had been convicted of terrorism in France. Then there is Khalil Said al-Deek (AKA Joseph Adams), the US-Jordanian with ties to Bin Laden who was killed by a Pakistani agent in 2005. While al-Deek is not mentioned in the film, the New York Times reported that US intelligence suspected al-Deek of collaborating with Moazzam Begg on a CD-ROM version of an “Encyclopedia of Jihad.’

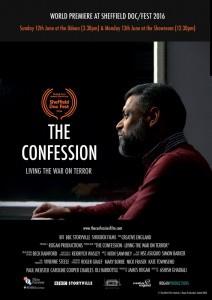

Producer James Rogan (BBC Storyville: Amnesty! When They Are All Free, The Trouble with Pirates, Blog Wars), and Executive Producer Roger Graef OBE (Great Ormond Street, Feltham Sings) who made the film for an upcoming BBC Storyville episode, do not always ask the questions we might want to ask.

For one thing, unless I missed it, apart from the bookshop, we never learn how Begg provided for his children, wife, world travels and charitable contributions before his release from Belmarsh. Now, he apparently lives off his life of wrongful imprisonment: travelling the potentially lucrative lecture circuit and writing an autobiography. He has apparently received a large amount in compensation from the US and UK governments, although, again, this is not mentioned in the film.

Since Begg’s parents emigrated from Pakistan, you might possibly understand why, in 1998, he moved his wife (he married in 1995) and young children from the UK to Peshawar, (where, incidentally, Khalil Deek was living). But it is more difficult to swallow the decision to move to Kabul, Afghanistan in 2001.

Begg says in the film: ‘I didn’t join the Taliban, I lived under them.’ Fine for men with beards like Begg, but what about his family? Begg tells us with a straight face that ‘girls could have education as long as it’s based on the Quran.’

In 2002, Begg tells us that he was sleeping in Islamabad when his house was raided and he was thrown into a vehicle– en route for Guantanamo Bay (where, he claims, the guards treated him well, but where the ‘experience of solitary confinement was destructive.’) Apparently, from the vehicle, he managed to call his father to alert him that his wife: ‘doesn’t speak the language and doesn’t have money.’

You have to wonder what kind of life his wife had (by then they had 3 of their 4 children) left alone without access to her own money or being able to speak with the community around her.