There can be few of us who have not heard his name and equate it with the care and welfare of children, primarily orphans, but what do we know about the man himself?

Born in Dublin in 1845, Thomas John Barnardo was a workaholic Irishman whose nonstop efforts in the cause of children’s welfare landed him in an early grave at the age of sixty.

In Victorian Britain poverty was considered the norm. The wealthy thought destitution was the fault of paupers and was treated as a crime.

Early life

Thomas John Barnardo was born to John Barnardo and Abigail in 1845. At the age of 16 he converted to Protestant evangelicalism. Just before his 17th birthday he decided to become a medical missionary in China and so set out for London in 1866 to train as a doctor at the London Hospital in Whitechapel.

Arrival in London

Victorian London in the 1800s was a city with many problems. After the Industrial Revolution the population had dramatically increased and much of this increase was concentrated in the East End, where overcrowding, bad housing, unemployment, poverty and disease were rife.

A few months after Thomas Barnardo arrived in London an outbreak of cholera swept through the East End killing more than 3,000 people and leaving families destitute. Thousands of children slept on the streets and many others were forced to beg.

The Ragged School

In 1867, Thomas Barnardo set up a Ragged School in the East End, where poor children could get a basic education. One evening a boy at the Mission, Jim Jarvis, took Thomas Barnardo around the East End showing him children sleeping on roofs and in gutters. The encounter so affected him he decided to give up on his dream of going to China and dedicated himself to helping destitute children.

In 1870, Barnardo opened his first home for boys in Stepney Causeway training boys in carpentry, metal work and shoemaking. These skills enabled the boys to secure apprenticeships and work.

No child should be turned away

At first Barnardo limited the number of boys who could use the shelter. However, one evening, an 11-year old boy, John Somers (nicknamed ‘Carrots’) was turned away because the shelter was full.

Two days later Carrots was found dead, the cause malnutrition and exposure. From then on Barnardo vowed never to turn another child away and a sign was hung stating ‘No Destitute Child Ever Refused Admission’

In the space of seven years or so, and still not thirty, Thomas Barnardo had established a Ragged School, a home (and employment agency), and a mission church. He had acquired more than a dozen properties in east London – and even published a children’s magazine.

Marriage and Barnardo’s village

In 1872 Barnardo purchased the lease of The Edinburgh Castle, a gin palace and music hall in Limehouse, and converted it into a coffee house and mission church. This bold gesture brought him the support of wealthy and influential evangelicals who backed his work with children.

In 1873 Thomas Barnardo married Syrie Louise Elmslie – a fellow evangelist and philanthropist. As a wedding present, they were given a fifteen year lease on Mossford Lodge, Barkingside.

This 60 acre site at last enabled Barnardo to open a home for Girls. The Girls’ Village Home was developed and within three years Barnardo had purchased the lease and owned the land. By 1900 there were 65 cottages, a school, a hospital and a church around three village greens.

By the 1920s the village would able to house 1500 girls. Barnardo’s ethos of good training continued with the girls and they were trained mainly for domestic service. The training was so good the girls were sought after by royal and society households. Girls were also trained as nursery nurses and Barnardo’s pioneered the first Nursery Nurse training scheme.

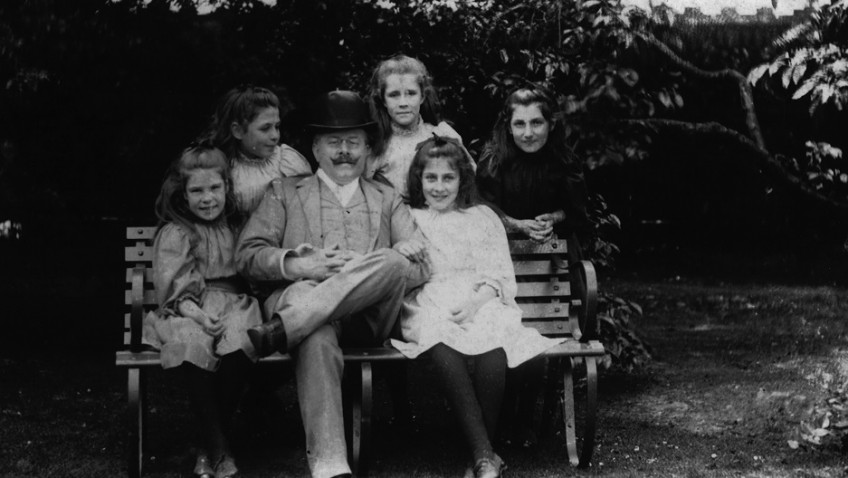

Thomas and Syrie had seven children, including Marjorie who was born with Down’s syndrome. According to Syrie’s memoirs, Barnardo was devoted to Marjorie and his experience of caring for her influenced his approach to the care of disabled children. The charity accepted children with both physical and learning disabilities and very early on Barnardo set up several specialist homes for children with disabilities.

By the time Thomas Barnardo died in 1905, the charity he founded had opened 96 homes caring for more than 8,500 children.

Next year the Charity will be celebrating its 150th anniversary so it is a good time to be looking at the magnificent work it does. We should be very interested to hear of any memories or stories of the children who were helped by this famous organisation so please get in touch if you can help.

For more information about Barnardos and what it does today have a look at www.barnardos.org.uk

Were you brought up in a Barnardo’s home if so we’d be really interested to hear your story?

Thanks to Amberley publishing for the images and their fascinating book Doctor Barnardo, Champion of Victorian Children written by Martin Levy and published in paperback on 15th August 2015.