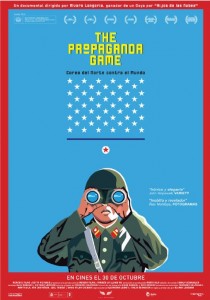

Joyce Glasser reviews The Propaganda Game (February 26, 2016)

Any documentary that takes us inside the Hermit Kingdom of North Korea will be of interest, and in The Propaganda Game, Spanish documentary producer/writer/director Alvaro Longoria shares the highlights of his 10-day visit with us. The visit is so tightly controlled, however, that we learn more about the propaganda game than about North Korea. Perhaps that is the point: propaganda is an acknowledged instrument of state, and the brainwashing of the population, as we see, starts shortly after birth with nursery songs that praise the country’s dictators.

So it is perhaps fitting that Longoria ushers us into Pyongyang as though it were Brigadoon. To romantic music, the camera pans across impressive buildings, spotless streets, children skate boarding in a specially designed park, and a smiling, handsome couple celebrating a marriage. Everyone we see, except the portly Alejandro and the obese Kim Jong-un are thin. That said, in a larger-than-life statue his corpulence is normalised. A journalist and various talking heads from human rights groups tell us of food shortages when the Chinese economy collapsed.

Longoria and his two-man crew were only allowed into the country with the assistance of an apparently self-appointed Special Delegate of North Korea’s Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, Alejandro Cao de Benos. Longoria contacted Alejandro on Facebook, and after a year, he was granted access with conditions so strict that Longoria and his two-person crew had to follow a strict itinerary and were only once (when they were in the van) left alone.

Longoria and his two-man crew were only allowed into the country with the assistance of an apparently self-appointed Special Delegate of North Korea’s Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, Alejandro Cao de Benos. Longoria contacted Alejandro on Facebook, and after a year, he was granted access with conditions so strict that Longoria and his two-person crew had to follow a strict itinerary and were only once (when they were in the van) left alone.

Alejandro alone is worthy of a documentary. A Spaniard, like Longoria, Alejandro is known as the only foreigner working for the Korean Government although even this has to be taken with a grain of salt. Neither his name nor his position appears on any official government register and Alejandro travels on a Spanish passport. Alejandro, who clearly enjoys the limelight, has the party line and propaganda down so pat that he is useless in providing us with any insights or useful information. Longoria’s repeatedly asks where all the money comes from, but receives no reply.

We are taken into a museum that looks like a cross between Versailles and a Las Vegas casino. It is empty, but that could be because it is full of propaganda that everyone has seen on school trips. The state offers its people free housing – in large, grey soulless blocks, though they have no choice as to where they live. They get free medical care, although many operations, procedures and medicine are not available. They are given free education, although the student must be willing to study what the state dictates.

We are also taken into a Church as an example of the nation’s religious freedom. Only political religions, like the Church of Scientology are prohibited, although this prohibition seems to include Judaism as well. This is where we see the propaganda game in full swing as the Church service is nothing short of surreal, with a ‘temporary’ priest on hand (the alleged ordained priest being indisposed) and the congregants looking like extras from central casting.

The closest Longoria comes to interviewing a person on the street is a moment when he stops a man to ask him if he is happy, naturally, through a translator. His answer is irrelevant, of course, as the poor man looks petrified and knows better than to say what he really thinks. The most telling sign of his fear are the beads of sweat on his neck captured by the camera.

But all the censorship that the crew is subjected to cannot prevent the camera catching a few cracks in the Kingdom’s defences. We have a glimpse inside a family home and see what must be a video or DVD of Pixar’s Brave playing on the television after Alejandro tells us that American television is prohibited. A little boy seems to be a fan of Barcelona’s football team, and a Coca-Cola emblem appears on a fast-foot stand. Alejandro tells us that they have to purchase refrigerators from China and they come that way.

As for the blockade, Alejandro explains the row upon row of HP computers in an empty university hall as being evidence that the blockade has no affect on his country. HP is not asked to comment.

After leaving North Korea, Longoria discuses the future of the North Korean people with several experts. It seems that only the USA wants unification. China finds it convenient to keep North Korea as a place to dump product, and as a buffer against Japan and the non-communist far east. It is also a handy bargaining tool as North Korea has to listen to China to some extent. Japan fears a unified Korea would create a potentially powerful rival while South Korea is vehemently opposed as it would be saddled with the enormous cost of unification.

The Propaganda Game is as fascinating for what we do not learn and see as for what we do. The very existence of Longoria’s documentary contributes to the game. Viewers will have to make up their own minds as to who has won this particular round.