Truman and Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation (April 30th on Dogwood on Demand and other digital platforms) Cert. TBC, 86 mins.

According to Truman Capote, he was 16 and Tennessee Williams was 29 when they met in 1937. Both would enjoy early success and attention, and both had stellar careers and wealth before them. In 1983, they had dinner together a few weeks before Tennessee died from an overdose of barbiturates (like Truman’s mother). Truman died 18 months later, at 59, of liver disease and drug intoxication.

Lisa Immordino Vreeland, the director of the fascinating documentary biopic Peggy Guggenheim: Art Addict, also made a documentary about her grandmother-in-law, the legendary Vogue Editor, Diana Vreeland. She now tackles the complex lives and relationship between two American male legends from the mid, and second half of the 20th century.

The two greatest writers of their generation to come out of the American South, the playwright Tennessee Williams and novelist and socialite, Truman Capote had, in Truman’s words, ‘a sort of intellectual relationship though people inevitably thought otherwise.’ Despite the recently released documentary The Capote Tapes, Vreeland’s extensive, painstaking research brings us new insights into this elusive talent, while bringing us one of the first biopics of the mesmerising Williams.

Ambitiously, Vreeland structures her film as a dialogue between the two writers. This devise can be confusing as she has actors Jim Parsons (Williams) and Zachary Quinto (Capote) – both fabulous – reading from a wide variety of their letters, memoirs, and journals, while showing us archival interviews (in one case, they are both interviewed by David Frost) in which we hear their real voices and see them in person. Moreover, the interviews are not always dated or labelled, and many viewers will not know who interviewers Dick Cavett and Merv Griffin are. But these are minor irritations in a revelatory and moving portrait of two flawed geniuses whose 40-year distant relationship was in turn malicious and disdainful, generous, humorous and supportive.

They knew they shared the loneliness of the obsessive writer, but they had more than that in common. Both were gay, both born into broken, poor and dysfunctional families, both became rich (travelling extensively through the top 1950s European resorts) and famous through their often-autobiographical work and both became depressives, alcoholics and drug addicts as their careers and personal lives suffered setbacks. Both were also jealous, although Tennessee hated himself for being jealous of other Broadway playwrights despite having won two Pulitzer Prizes, two NY Drama Critic Awards and a Tony Award.

But they were very different people. Nowhere do we discover their contrasting personalities (Tennessee comes across as honest, generous and compassionate; Truman as a cold, distrustful chameleon) more than when, in his unfinished satire of NYC’s upper crust society, Answered Prayers, Truman creates the character of Mr Wallace. Tennessee was instantly recognisable, if only by the physical description. This prompted Tennessee to call Truman a liar, to which Truman responded, ‘art and truth are not necessarily compatible bedfellows’.

Defensively Truman says that Proust also took his characters from real life to which Tennessee retorts, ‘but I don’t think any of them were drawn maliciously.’ Tennessee comments, ‘there is a sense in which all creative work and all fiction is imagination, but that imagination is not the same as bitchery and lying.’ Ouch!

Secure in the moral high ground, he adds, ‘we must try to go forward in this world without trampling over others.’ This is not rhetoric. Tennessee means it and this statement sounds like the plea for compassion that underlies all of his plays.

Speaking of which, arguably the most thrilling part of the film is the discussions (with film clips) of their respective film adaptations. As we go through the film clips, and hear Truman’s comments, we appreciate how the writing of In Cold Blood reveals as much about Truman as about the murderers; and to what extent Tennessee’s anguished plays and film adaptations are autobiographical.

It is particularly heart-breaking to hear him talk about his sister Rose when discussing Suddenly, Last Summer, about a mother (Katharine Hepburn) in denial who has her niece (played by Elizabeth Taylor) lobotomised because she, the aunt, cannot face the truth that her niece has repressed. Tennessee’s mother had Rose institutionalised and lobotomised. Equally painful is the strained father-son relationship in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (adapted from a 1952 short story). In the film adaptation Paul Newman plays an alcoholic closeted gay man who cannot please his despotic, wealthy father or produce an heir – despite having a wife who looks like Elizabeth Taylor. Tennessee was disappointed that in the film script, almost all his references to homosexuality were removed.

Tennessee reminds us that most of the major adaptations were made during the period of heavy film censorship, and the endings of all of his plays were changed “which almost contradicted the meaning of the plays. Unless you have seen the plays, you wouldn’t know what they were about.”

Tennessee wrote The Fugitive Kind for Marlon Brando and Anna Magnani (who were cast) while Truman had Marilyn Monroe in mind for Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Paramount ‘double crossed me’ Truman recalls, by miscasting Audrey Hepburn in that role. What Truman was describing through the character of Golightly was one of the “tough girls” he met every day. ‘Not exactly call girls, who come to New York; briefly; spin in the sunshine for a while like mayflies and then disappear.’ But close enough. He was disappointed that by this sanitising of his novel he was denied the opportunity to ‘rescue one girl from anonymity and save her for posterity’.

You can read our review of The Capote Tapes by following this link.

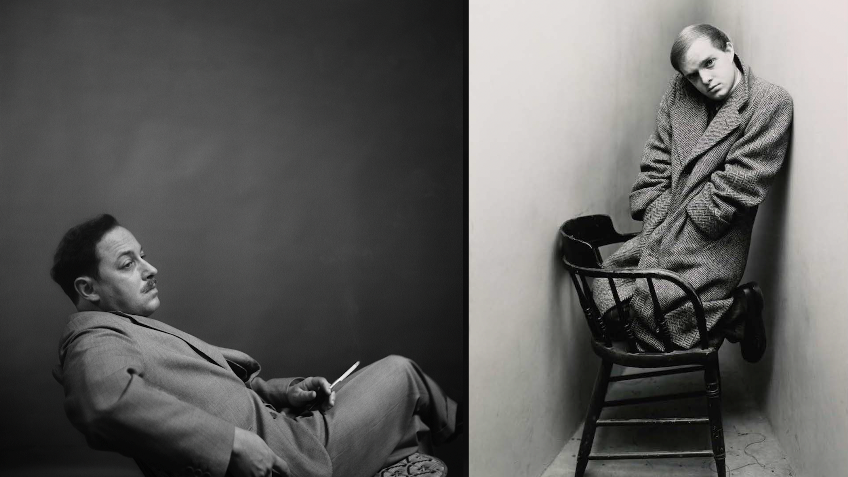

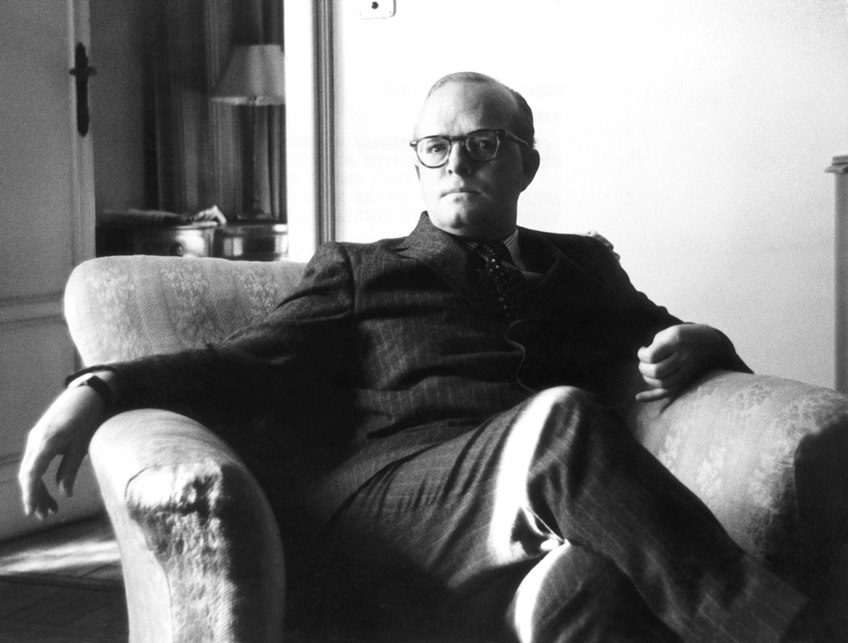

Main image: An Intimate Conversation. Photo of Tennessee Williams Courtesy by Clifford Coffin & Truman Capote, 1948 by Irving Penn © The Irving Penn Foundation.