Sunflowers (June 8, 2021) Cert U, 90 mins.

‘Now that I hope to live with Gauguin in a studio of our own,’ wrote Vincent Van Gogh from his new home in Arles, ‘I want to make a decoration for the studio. Nothing but big sunflowers.’ True to his word, he painted seven of what are among the world’s greatest flower paintings, and the paintings that encapsulates Van Gogh. Painted rapidly first in 1888, and then in 1889 in Arles, these exuberant flowers, all in makeshift vases, surpass the four sunflower paintings he did in Paris (1886-1888), which are, notably dark, and lying, as though gone to seed on a flat surface.

Captivated by his first encounter with the Impressionists after living in Antwerp, and in particular, Monet’s 1880 Sunflowers, the self-taught artist began a two-year study of colour, painting some 40 flower still lifes in Montmartre where he lived with his art dealer brother, Theo. He hoped they would prove commercial.

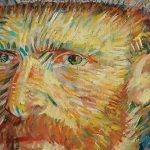

Based on the 2019 exhibition Van Gogh and the Sunflowers at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, Exhibition on Screen’s David Bickerstaff (co-writer-director) and Phil Grabsky (co-writer-Producer) have given us another informative and fascinating documentary that combines the emotional and sensory joys of a Van Gogh exhibition with the intellectual context provided by an insightful group of experts who complement them. As Martin Bailey, author of The Sunflowers are Mine, points out, we are as fascinated by Van Gogh’s remarkable life (his entire painting career was ten years) as we are by the art it expresses.

The title of Bailey’s book is taken from a quote from Van Gogh’s beautiful, expressive letters (read by Jochum Ten Haaf) where he recognises his place among the French impressionists known for their flowers: ‘You know that the peony is Jeannin’s (Georges Jeannin, 1841, 1925), the hollyhock belongs to Quost (Ernest Quost, 1842-1931), but the sunflower is somewhat my own.’

Van Gogh’s dream of an artist colony in the sunny south of France to rival Gauguin’s colony at Pont-Aven in Brittany, began and ended with Gauguin’s October to Christmas 1888 stay in and around The Yellow House. The joy that shines through Van Gogh’s painting of his rooming house in Arles, matched his new optimistic attitude upon leaving Paris for the bright, warmth and calm of Provence. The yellows and blues of the Yellow House were to be the colours of his sunflower series, although several are extraordinary tonal studies in painting yellow on yellow and variations of yellow to capture the Helianthus species.

We are given some horticultural context for French society’s new interest in sunflowers, primarily from Stephen Harris, Druce Curator of the Oxford University Herbaria. The North American Helianthus was unknown in Europe before the discovery of America in 1492 and, even in Van Gogh’s time, they were garden plants, and not grown in fields like today. The sunflower is actually thousands of tiny three-part flowers, and only the dark brownish/yellow centre produces seeds.

Though the sunflower does not, as once thought, turn towards the sun, the great Dutch painter Van Dyck uses its association with royal patronage “waiting on the sonne of maieste” in his Self-Portrait with Sunflower circa 1633. That was the year Charles I gave Van Dyck the gold chain he holds in the portrait while pointing to a giant sunflower. This might suggest he looks to his master, the British King, with the flower being either the King, himself or a symbol of art. Van Gogh’s arrival in Paris corresponded with the period when realist flower painting, co-existed with impressionist flowers, both catering to a market that valued beauty on their walls and the symbolism (mortality, friendship, devotion) that flowers connote.

The focus of the exhibition is on the sunflower painting owned by Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, and his remarkable drawings, which many of us will see for the first time. The exhibition goes into some of the technical research done in preparation for the exhibition. For example, Van Gogh never used varnish, but subsequent conservators in the 20th century have done, and it is now dangerous to try to separate the once vibrant colour from the varnish which has distorted it.

The focus of the film, however, is the story, or stories, behind the seven sunflower paintings made in the Yellow House in Arles. A minor criticism is that this proves a bit confusing as there is some jumping around. Moreover, the variations in public galleries are not only similar, but, after Gauguin’s departure, Van Gogh painted three “copies”, or variations of the painting that is now in the National Gallery, London.

The first version (a turquoise background) is in a private collection and was last seen in 1948. The second, a royal blue background, with two of the flowers drooping over the vase, was destroyed in a 1945 fire started by American bombs over Ashiya, Japan. Munich’s Neue Pinakothek has the flowers against a blue-green background, and London’s is a yellow-on-yellow background. The 1989 so-called repetition are at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Van Gogh Museum (yellow background) and in the Sompo Japan Museum, Tokyo, (yellow-green background).

The Arles paintings are notable for their flatness, and lack of perspective and shadow, a technique Van Gogh adopted from Japanese art (as shown in Exhibition on Screen’s documentary Van Gogh & Japan). They are also notable for his heavy application of paint that turns the paintings into objects with personalities.

It is perhaps our own version at London’s National Gallery – one of the two hanging in Gauguin’s bedroom upon his arrival – that has the most moving story. Upon Vincent and Theo’s deaths in 1991, Theo’s new wife and widow, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger was left with her baby, Vincent, and stacks of unwanted Van Gogh’s. Johanna worked tirelessly to promote her brother-in-law’s art and reputation. She succeeded so well that in 1923, the wealthy British textile magnate and collector, Samuel Courtauld made a gift to the Gallery of the Postmaster Roulin from Arles.

But such was the growing recognition of the Arles sunflowers that the gallery quickly asked to swap it for the sunflower painting that had been hanging in Joanna’s bedroom for over 30 years. She finally succumbed to the National Gallery’s pleas, selflessly thinking of the pleasure it would have given Vincent and Theo to have it displayed in such a prestigious institution.

Sunflowers is in cinemas across the UK including Curzon, Everyman, Odeon, Picturehouse, Showcase, Vue and independent cinemas. Find your nearest cinema here.

You can read our review of Van Gogh and Japan here.

Joyce Glasser, Mature Times film critic.