Long Bright River by Liz Moore (published by Windmill Books, paperback pp 448)

That Liz Moore’s Long Bright River is on Barack Obama’s list of 2020’s best reads is not surprising. On his list, there are other books by female writers that explore the inequalities in America, the plague of opioids, corruption and the challenges to the American Dream. These include, Isabel Wilkinson’s Caste, Karla Cornejo Villavicencio’s The Undocumented Americans and Anne Applebaum’s The Twilight of Democracy. What distinguishes Long Bright River, is that it is a novel, and one that has all the commercial elements of a novel that is probably being adapted for cinema or as an on-demand series as you read it.

Some of these elements are so familiar from innumerable BBC 4 and Netflix television series as to be clichés, chief among them, the policewoman with a few big secrets and an unorthodox private life, who goes out on a limb; There is also the mandatory police corruption; prostitution and a serial killer on the loose in a grimy city’s mean streets.

Even the basic plot of two, disadvantaged, orphaned sisters, one joining the police force, the other becoming a drop-out relying on elicit acts to feed a drug habit, sounds familiar. Also, from Pennsylvania, (Pittsburgh), prolific novelist John Edgard Wideman’s landmark memoir, Brothers and Keepers tells the story of an African American author and Ivy League university professor’s struggle to help his younger brother, a serial criminal who is finally sentenced to life in prison.

Yet Moore gives all these tropes a twist and creates a messy, dirty, imperfect world of betrayal, cheating, violence, prejudice, integrity and love; a world we inhabit until the last page of the book. This world is full of characters who appear and reappear in unlikely places. It has plenty of bad guys (some in the police force), but few saints as everyone, including Mickey, is flawed. Patrol Officer Michaela “Mickey” Fitzpatrick’s world is never easy to navigate, but it is always plausible. For it is a recognisable world full of exploited innocence, family troubles, social inequality, human foibles, false assumptions, and foolhardiness that is indistinguishable from small acts of heroism.

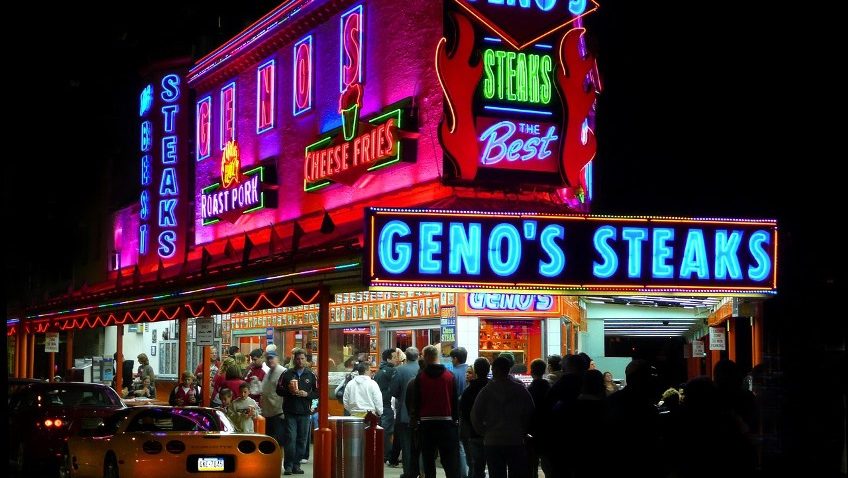

Mickey is a single mother and a Philadelphia Police Force (PPF) patrol officer in Kensington, a high-crime district of the city. The book jumps seamlessly back and forth in time, driven by Mickey’s involvement in the search for her missing sister as a serial killer targeting prostitutes is on the loose.

When we first meet Mickey, she has just been assigned her new patrol partner, Eddie Lafferty, 43 to Mickey’s 32, and, unlike Mickey, a late comer to the force. Also, unlike Mickey and her former partner of ten years, the dependable Truman, Lafferty is loquacious. If you pay attention to some of his comments when they come across Lafferty’s first body, that of a Jane Doe, and no doubt a sex worker, you can understand why Mickey soon decides to request to work alone.

But no one is discarded in this novel, including Lafferty. Characters turn up in new contexts at which point you learn more about them. When halfway through the novel, Mickey calls on Truman, who has taken early retirement after being injured, she learns more about him than she knew during their long partnership on the force.

Mickey and her younger sister, Kacey, grew up in Kensington and, after their drug-addicted mother, Lisa, died (Mickey was 5 ½ and Kacey just 4), they were left under the guardianship of their unaffectionate, inattentive grandmother, Gee. According to Gee, who blames Lisa’s demise on her drug-addict husband, their father disappeared wanting no part in his daughters’ lives. While Gee has her own selfish reasons for lying, Moore humanises her, describing the tough, menial jobs that fill her empty life, her grieving for her only daughter, and her willingness to, at least, put a safe roof over her granddaughters’ heads. To survive in this joyless household, the two sisters form a tight bond and sleep in the same bed even though there were two spare bedrooms in the house. When the two sisters become teenagers, their lives diverge.

After school day care presents a problem for Gee, who enrols the girls in a free program run by the Police Athletic League. It is here that Mickey falls under the spell of Officer Cleare, a handsome 27-year-old, educated officer who, recognising Mickey’s potential, encourages her to read and teaches her chess. Mickey likes Cleare’s quiet authoritative nature, but Kacey dislikes him for this reason, as she grows up wary of any authority. It is Officer Cleare who inspires Mickey to enter the police force (she was going to study history at University). As their student/mentor relationship develops into something more, the reader is left to ponder whether it was love or manipulative grooming that drove the relationship.

Moore’s direct, compelling first-person style is sometimes self-conscious and overdone, as when she opens an early chapter, “the first time I found my sister dead, she was sixteen.” Nonetheless, it is Mickey’s semi-reliable narrator who will keep you reading even though this is not a page turner. It is not difficult to figure out “who dun it” (Moore drops early clues) although, as in the best of crime novels, it is the descriptions, and the daily lives and relationships of the characters, that are more important.

And there are plenty of characters, from Mickey’s landlady, Mrs Mahon, who has to be the most accommodating landlady in literature and an always available child minder for Mickey’s son, Thomas. More characters appear at a Thanksgiving reunion with the estranged cousins from the maternal side of the family that rings true in every way. ‘As always at O’Brien family party functions, I am alone,’ Mickey says. If the family are wary of a cop in their midst, Mickey has a motive other than pleasing Thomas for showing up: She wants some information about her sister’s whereabouts. The city’s drug underworld also offers an array of shifty characters, and just as many red herrings.

The title is taken from Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem, The Lotus Eaters, but takes on a new metaphorical meaning particularly as the novel is bookended with a list of those carried off by the endless river of sorrow and hope that runs through Kensington.