The biggest laugh at the English premiere of Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion in 1913 was when Eliza Doolittle rejects an offer of a walk across the park with a “Not bloody likely!” It was the first time “bloody” had been heard on the London stage. 110 years on, it is still the biggest laugh.

Since 1956, Shaw’s witty play has had to compete with Lerner and Loewe’s musical adaptation, My Fair Lady, and Rex Harrison’s definitive performance as Henry Higgins. It was not seen again in London for 21 years. Revivals are rare. One every decade. It would have been nice to see Pygmalion staged more realistically and well-cast throughout.

“It is,” wrote Shaw in his Preface “impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman despise him.” Richard Jones’s intrusive and irritating production, updated and unattractively designed, is very disappointing.

Henry Higgins, a professor of phonetics, takes up a challenge to transform Eliza Dooliittle, a cockney flower girl, into a duchess within six months. Egoist and bully, rude and overbearing, selfish and arrogant, he concentrates on the speech and ignores the woman, not giving a moment’s thought to what will become of her when the experiment is over.

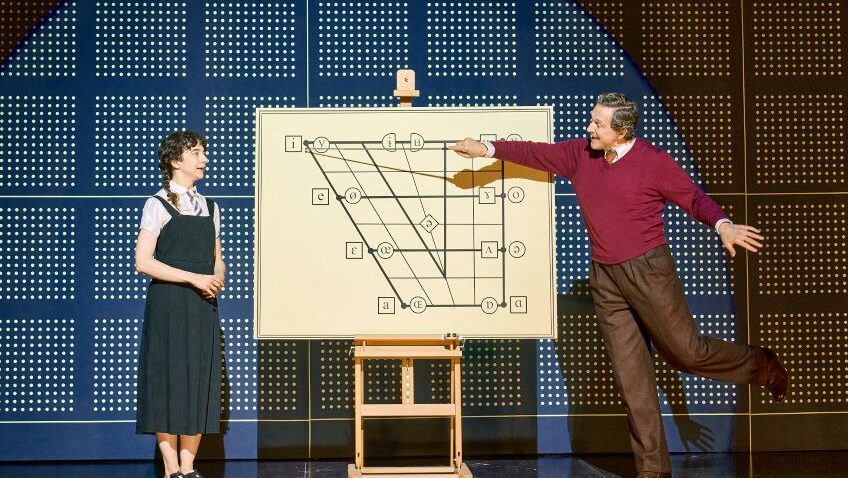

Bertie Carvel never feels right as Higgins, either physically or verbally. His diction is such that he is often inaudible. His lecture on pronunciation, an unwanted addition, is crude revue sketch stuff and not funny and should be cut. Shaw in his stage directions says that Higgins remains likeable even in his least reasonable moments. Carvel’s Higgins is never likeable.

The difference between a lady and a flower girl is not how she behaves but how she is treated. Patsy Ferran’s Eliza looks so frail at the embassy ball that her brilliant success is not believable. The clothes she wears do not help her in her transformation from snivelling guttersnipe (Higgin’s words, not mine) to self-assured lady.

Alfred Doolittle, Eliza’s dustman father, is a blackguard with no morals. As one of the undeserving poor, he can’t afford them. John Marquez’s performance is perhaps more suitable for a farce or a musical comedy; but he is undeniably funny when he is propelled, much against his wishes, into middle-class morality.

To learn more about Robert Tanitch and his reviews, click here to go to his website.