Joyce Glasser reviews Three Minutes: A Lengthening (December 2, 2022) Cert 12A. 69 mins.

On 30 November you can watch a preview with a Q & A with the filmmakers, narrator Helena Bonham Carter and producer Steve McQueen. For more information follow this link.

Someone could write a book on the number of precious items stashed away in attics and uncovered by chance by relatives or unrelated homeowners, often unaware of the value of their find. In 2013 a previously unknown Van Gogh, Sunset at Montmajour, was found stashed in a Norwegian attic where, apparently, it had been for 85 years. While repairing a leaky roof in Toulouse in 2014, a homeowner discovered a Caravaggio. Last year, a Tiepolo drawing was found in bubble wrap in the attic of Weston Hall.

And then there is Glen Kurtz’s chance discovery of an innocuous bit of shrunken, damaged holiday footage found in his grandfather David’s attic in Florida over 70 years after that holiday. It was shot by 50-year-old David in 1938 when a detour from his European grand tour took him to his birthplace, Nasielsk, a Polish town on the Ukrainian border, population 7,000. Almost half, or 3,000, of the population was Jewish, the majority working in the town’s button factory.

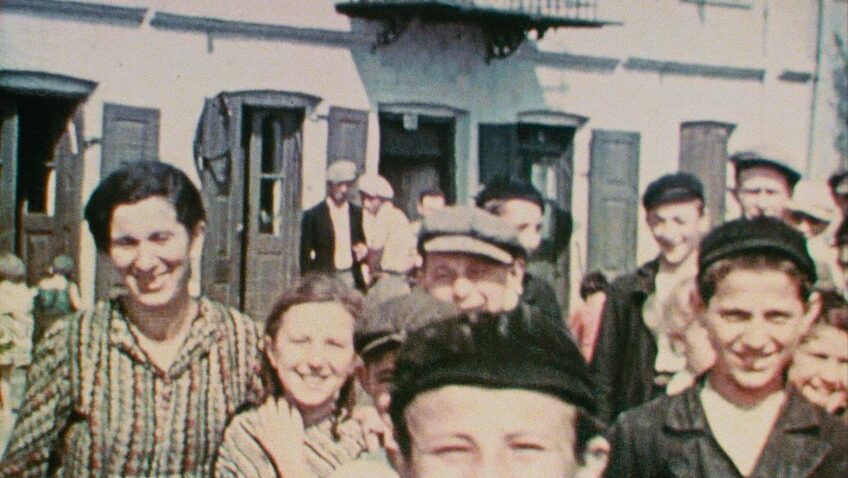

Smiling as he leaves his rented black sedan near the front of what was identified as the main synagogue, David’s camera captures the smiling faces and animated movements of some 150 Jewish men, women and children, who had congregated there, possibly for the visit of the famous cantor (and wartime opera singer) Moshe Koussevitzky, who ten years earlier had become Warsaw’s chief cantor.

Just over a year later, none of those faces remained in the town. Only 100 of Nasielsk’s Jewish inhabitants survived the Holocaust. No memorial marked the spot where, with those few exceptions, the entire Jewish population was brutally evicted, inhumanely deported and sent to their executions.

As Glen Kurtz reminds us, memorials are usually built around names. In this case, there are only faces. In Bianca Stigter’s haunting investigative documentary, Gradually some of those faces are matched with names and even identities.

Beautifully narrated by Helena-Bonham Carter, Stigter’s documentary, adapted from Glen Kurtz’s book, Three Minutes in Poland, Discovering a Lost World in a 1938 Family Film, shows how his painstaking research into the anonymous faces, the clothing, the weather reports and the buildings in the footage has changed our knowledge of history by adding this link to the chain. It has also resurrected a ghost town and acted as a memorial to dozens of lost victims of the Holocaust.

First there is the sound that brings us into the film. The familiar sound of film being cranked through an old projector. In 1936 Kodak introduced Kodachrome film, the first commercially successful amateur colour film, and a year later a new home movie camera was announced that used 16mm film in magazines. In 1938, Kodachrome duplicating film in 16mm was on the market. David Kurtz, who left Poland as a child and became a middle-class American, was an early adapter and, in preparation for the trip, had just purchased his first home movie camera, which, as the footage shows, he was getting used to.

By the time Glen found the film it was just months away from being unsalvageable. It was restored to the extent we see today by the Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and thanks to being placed on its website, has led to additional identifications of the people in the film.

One woman who watched the video on the museum’s website recognised her grandfather. Then the thirteen-year-old Moszek Tuchendler, now the eighty-six year old Maurice Chandler, who resides in Florida, speaks in the film and provided Glen with a precious eye-witness account. With his help, Kurtz locates six more survivors. One a ninety-six-year-old woman, stands next to the man she would later marry.

From the caps the boys are wearing, social and religious distinctions appear, indicating that this gathering combined people who might not have been friends or associates. The Orthodox Jews do not appear at all.

The lion on the door of the building from which the crowd exits, identifies it as the Synagogue. A sign over a shop and a woman who emerges from it could, if it were legible, provide a clue as to her identity. The Polish for “grocery store” can be made out, but not the family name in smaller, disintegrated letters. A Polish researcher, using an archive of local businesses, counts the number of letters, eight, marking those of which she is certain, four, and one that could be a P, an R, or a B. In crossword puzzle fashion, she deduces that it was the Rotowska grocery store, but unfortunately, after that we learn nothing more about the Rotowskas.

A shortcoming of the film, which is Stigter’s impressive debut, is that the names of people whose stories are told are pronounced in Polish without captions, meaning few of us can write them down or otherwise remember them. It is also difficult to identify exactly who is speaking at various points in the film. We are also left wondering if David Kurtz heard of the deportations from Nasielsk during or after the war, and if so why he did not recognise the value of the footage at the time.

But this quibble disappears in the film’s gripping climax: the devastating description of the unthinkably cruel and sadistic eviction of a neighbouring town and then Nasielsk in October 1939. The camera focuses on the cobblestone square, where the Jewish inhabitants were ordered to meet early one morning with their basic belongings. Half were rushed through the mud, stumbling and losing their belongings, chased to the train station by police with whips as some of their Catholic neighbours applauded. The second group was herded into the synagogue where they sat in fear all day and night with no food or water, before being transported through Belarus to their deaths.

Wilko Sterke’s atmospheric music is completed by that of Warsaw born English violinist and bandleader Bert Ambrose (a contemporary of David Kurtz) and the faint tenor voice of Moshe Koussevitzky.