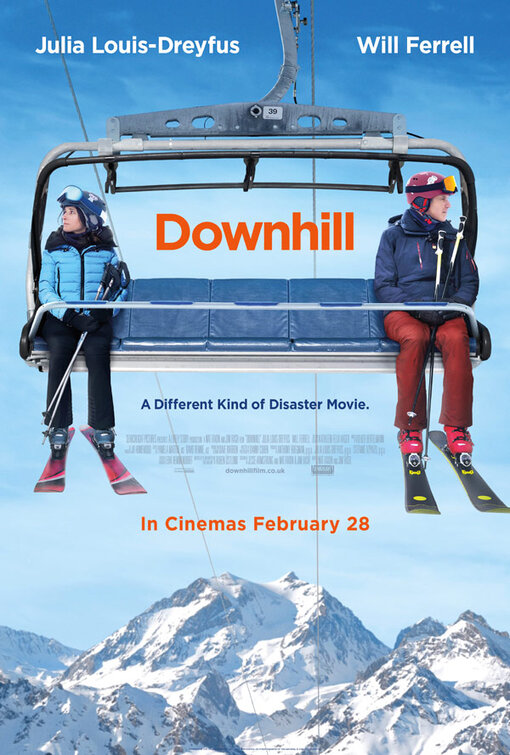

Downhill (February 28, 2020) Cert 15, 86 mins.

The problem with English language remakes is that while you do not want to remake a bad film, if you remake one of the best foreign films of the last five years, a lot of people might start asking what the point is. Such is the case with Downhill, the directorial debut of the talented American writing duo National Faxon and Jim Rash (The Way, Way Back, The Descendants). Downhill is entertaining and Julia Louis-Dreyfus and Will Ferrell give excellent performances as a couple forced to reassess their accepted roles in the family. But it is also a remake of Force Majeure a brilliant film by Swedish Ruben Östlund whose follow up, The Square, won the Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for an Academy Award. You can tell from the change of title that subtlety is not going to be one of Downhill’s strong points.

Force Majeure can be said to mean the pressure of circumstances or, an event that no human being could anticipate or control. Legally, such an event may relieve a person from an obligation or contract. But since only death can do a married couple part, would it relieve a spouse from a marriage contract? These concepts play around the title in the back of the viewer’s mind in Östlund’s film, whereas Downhill refers, quite clearly, both to the skiing holiday and the downward direction of a couple’s relationship.

Billie Staunton (Julia Louis-Dreyfus), an attorney, her husband Pete (Will Ferrell) and their sons (who look around 10 and 13), Finn (Julian Grey) and Emerson (Ammon Jacob) check into their ski resort hotel after getting a head start with an exhilarating run down the slopes. They are the picture of the wholesome family having fun and are looking forward to the holiday to unwind and spend quality time together. Pete’s father passed away eight months earlier and he has taken it hard. Billie wants Pete to leave work behind, too, although on his phone he is not working, but inviting a younger colleague who is travelling through Europe with his new girlfriend to meet them at the hotel.

They notice that there are no children in their hotel and are informed that the more crowded family hotel (with activities for kids) is on the other end of the resort. Throughout their time at the hotel they hear controlled avalanche explosions, set off to ensure that skiing is not interrupted by the real thing.

On the second day the family have lunch on the terrace of their hotel after a morning of skiing and the controlled, happy mood continues. Billie is in the middle of a bench of an outdoor dining table with the boys on either side of her. Facing them is Pete, alone on his bench which is closest to the exit. Suddenly, they see an avalanche comes cascading towards them from the mountain peak dominating the hotel like a tsunami. Billie instinctively wraps her arms around the boys, and they huddle together, unable to move. Pete’s reaction is different. The incident is over in a few minutes with everyone resuming their positions, but the family will never recover from the ramifications.

It is only when Pete’s colleague shows up with his new girlfriend at the couple’s suite for drinks, that Billie explodes in rage, telling her husband and his guests why his actions have troubled her.

So far so close to the original, except that Östlund’s eerily minimalist production design and unsettling bone-dry, black humour have been replaced by a ski resort we’ve seen before and broader humour; the kind that invites you to laugh rather than squirm. If Östlund’s film is closer to a thriller than a family drama, Downhill is somewhere between The War of the Roses, 45 Years, and the National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation. While Faxon and Rash drive a dark streak through the film, Ferrell and Louis Dreyfus are known for their ability to make us laugh.

To the credit of all involved, however, Östlund’s obsessions with gender malaise comes through in several cringeworthy scenes. When he takes the boys to the kids’ adventure park at the other hotel, he ruins his chance to reclaim the boy’s respect, and is punished the following morning when he finds the boys and Billie relaxing on the couple’s bed engrossed in a computer game. Ferrell knows how to play the emasculated father and husband and with this script, not much acting is needed for the point to come across.

The problem is that from the start Pete is the weaker of the two in the marriage; the needier and the more childish. When, during the avalanche, he reveals his true colours, it should be less of a disappointment to Billie or a surprise to the audience.

This makes the cruel “pick up” scene less convincing than in the original version. Pete and his colleague go off skiing, and when Pete, choosing his dad’s hat over a helmet, falls, they end up at a café. A single woman approaches Pete, telling him that her attractive girlfriend thinks he is the best turned out man on the slopes. In Force Majeure the husband is well dressed, young and handsome so what comes next is a huge attack on his ego. Pete, on the other, is hardly the type to turn heads and it does not help that he is dressed in a baggy, uncoordinated outfit. He does not seem the type who would take the flattery seriously.

In Force Majeure the couple are both very good looking, are clearly well off and they have two beautiful children, a boy and a girl. They are meant to be the perfect family envied by their social circle as having it all. And it is this façade that Östlund chips away at with a touch of sinister cynicism.

Significantly, the Swedish couple are also much younger than the Stauntons, and the husband is always at work, so it is perhaps more credible that the wife would not yet know her husband for who he really is – although the shock might be all the greater with the older couple. The children of the Swedish couple are also younger, and when they hear their parents argue, they cry in their room, afraid that their parents are getting a divorce. For some reason, this idea never dawns on the two oddly inexpressive boys in Downhill, even when their mother goes off skiing on her own.

Louis-Dreyfus is one of the producers of the film and she has had the script altered to give herself a meatier role with a greater range. She does an impressive job portraying a woman strong enough to engineer a way forward for the sake of the kids, but under no illusion about her marriage.