“Lost” memories of people suffering the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease could one day be retrieved just like the film Total Recall, scientists said.

They are stored but dementia sufferers are simply unable to access them.

Neuroscientists found mice in early stages of Alzheimer’s can form new memories just as well as normal mice but cannot recall them a few days later.

But they were able to artificially stimulate those memories using a technique called optogenetics, suggesting those memories can still be retrieved with a little help.

Although optogenetics cannot currently be used in humans, the findings raise the possibility of developing future treatments that might reverse some of the memory loss seen in patients.

Professor of Biology and Neuroscience Susumu Tonegawa at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said: “The important point is, this is a proof of concept.

“That is, even if a memory seems to be gone, it is still there. It’s a matter of how to retrieve it.”

Scientists studied two different strains of genetically engineered mice to develop Alzheimer’s symptoms, as well as a group of healthy mice.

All mice, when exposed to a chamber where they received a mild electric shock, showed fear when placed back there an hour later.

All mice, when exposed to a chamber where they received a mild electric shock, showed fear when placed back there an hour later.

But after several days only the normal mice showed fear – the Alzheimer’s ones had forgotten.

But while natural cues didn’t prompt the mice to recall their experiences, the memories were still there.

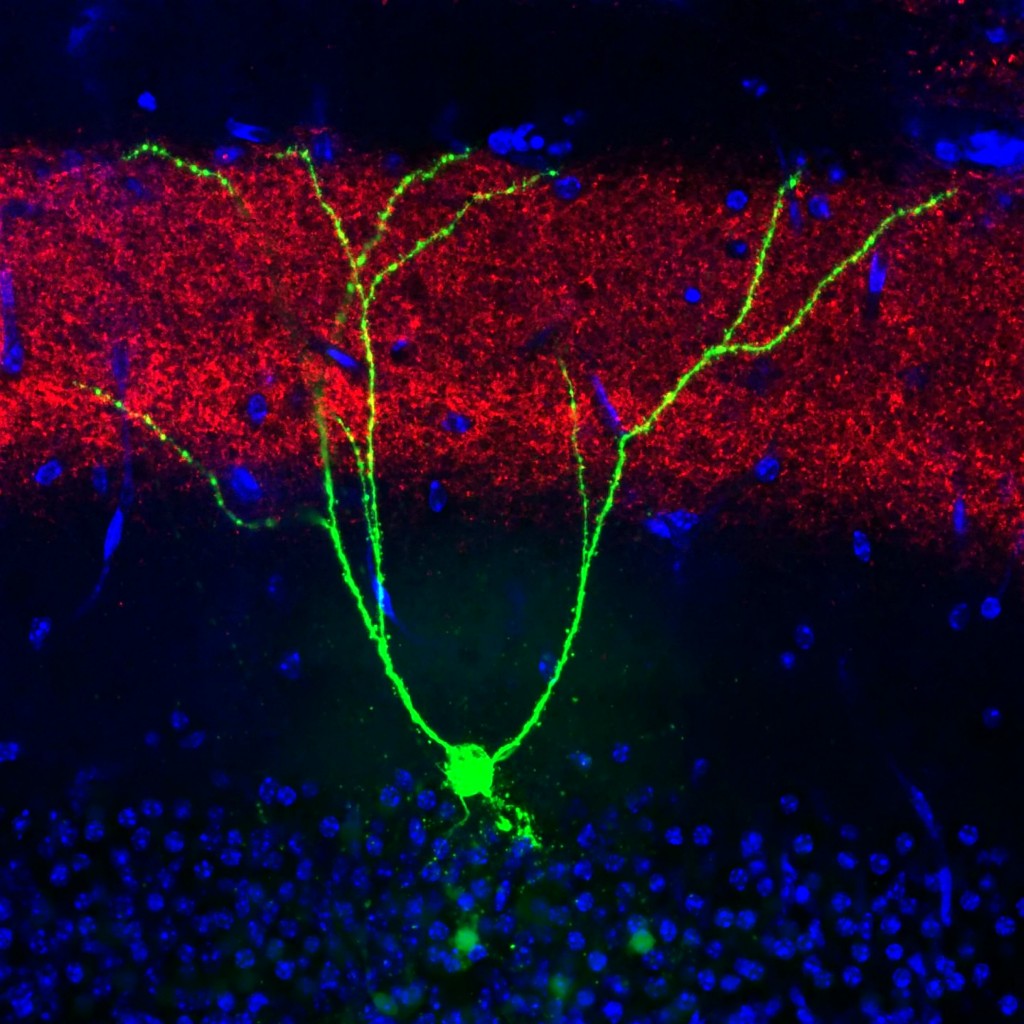

To prove this, researchers tagged the engram cells, cells that store specific memories, associated with the fearful experience.

Whenever these tagged cells were activated by light, the normal mice recalled the memory encoded by that group of cells.

Likewise, when the researchers placed the Alzheimer’s mice in a chamber they had never seen before and shone light on the cells encoding the fearful experience, the mice immediately showed fear.

PhD candidate Dheeraj Roy said: “Directly activating the cells that we believe are holding the memory gets them to retrieve it.

“This suggests that it is indeed an access problem to the information, not that they’re unable to learn or store this memory.”

Normally when a new memory is generated, cells corresponding to that memory grow new dendritic spines, buds that allow neurons to receive incoming signals.

But this didn’t happen in the Alzheimer’s mice.

The natural cue that should reactivate the memory, being in the chamber, had no effect because the sensory information wasn’t getting to the engram cells.

Researchers were also able to induce a longer-term reactivation of the “lost” memories by optogenetically stimulating new connections between the entorhinal cortex and the hippocampus using light.

A week later, the mice were tested again and this time they could retrieve the memory on their own when placed in the original chamber.

The approach didn’t work if too large a section of the entorhinal cortex was stimulated, so any potential treatments for humans would have to be very targeted – and optogenetics is sadly too invasive.

Professor Tonegawa who is director of the RIKEN-MIT Centre for Neural Circuit Genetics at the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory said: “It’s possible that in the future some technology will be developed to activate or inactivate cells deep inside the brain with more precision.

“Basic research as conducted in this study provides information on cell populations to be targeted, which is critical for future treatments and technologies.”

The study has been published in the journal Nature.

By Imogen Robinson