Joyce Glasser reviews The Lady in the Van

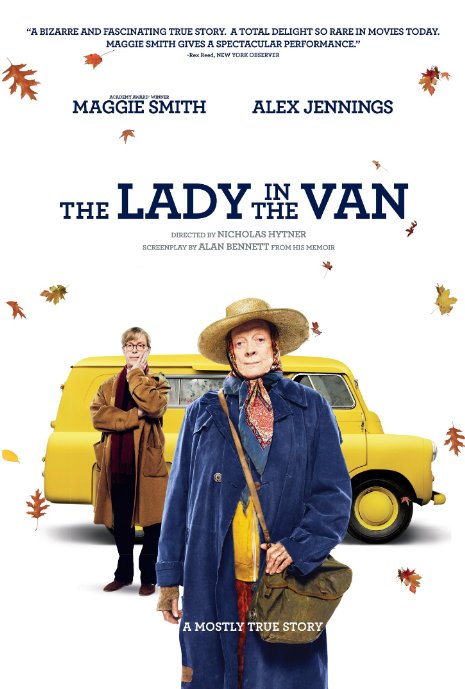

As we watch Nicholas Hytner’s (History Boys, The Madness of George III) film The Lady in the Van, with its screenplay from 81-year-old Alan Bennett and its 80-year-old star Maggie Smith, it is worth noting that this project, and these two ‘national treasures’ go back a long way.

A memoir entitled The Lady in the Van was published in the London Review of Books twenty-five years ago and then in stand-alone book form. A radio play starring Maggie Smith and Bennett himself quickly followed, and, in 1999, Bennett turned his memoir into a hit stage play starring Smith and directed by Hytner.

It is worth noting, because The Lady in the Van is more than a bitter-sweet comedy about an artsy-affluent neighbourhood’s nimbyist reaction to a smelly tramp (Smith) who camps on their leafy street. And to suggest as much, the principal location is Bennett’s own house and his actual street: Gloucester Crescent, NW1 between Camden Town and Regents’ Park.

Using Bennett’s real home is significant, as the film is also a thought-provoking look at how a writer uses people around him as the material for his art. We are again reminded of the real-life writer Bennett (not to mention of his long relationship with stage-director Hytner) by cameo appearances from Dominic Cooper (playing a theatre actor), and James Corden (a street trader).

They are now major international film and television stars, but in 2004 were little-known actors in Nicholas Hytner’s stage production of Bennett’s The History Boys, that, like Lady in the Van, was turned into a film.

But while the fourth-wall is broken by these real-life connections, the entertainment value of the story seldom suffers from it.

But while the fourth-wall is broken by these real-life connections, the entertainment value of the story seldom suffers from it.

Maggie Smith is a shoe-in for a Best Actress Academy Award nomination, despite stiff competition this year. The range of expressions and emotions we can read on her face, and the daunting physicality of the role are astonishing.

There are few actresses alive who could carry off this bag lady, a fine line between caricature and character, bathos and compassion, and annoying loony and intelligent victim.

That we care about Miss Mary Shepherd and can both laugh and cry as her life is laid out in increments, is a testament to the acting even more than to the writing.

Special mention must go to Roger Allam and Deborah Findlay for their truly brilliant comic turn as champagne socialists for whom charity goes only so far. As events involving Miss Shepherd delay their trip to the opera at Glyndebourne, some in the audience might recall that theatre/ opera director Jonathan Miller is a neighbour, as was the composer Vaughan Williams. Frances de la Tour (also from The History Boys) plays his widow in the film.

The relationship between a writer and those who unwittingly become his characters is the subject of Writer/Director Noah Baumbach’s dark comic film, Mistress America (August, 2015) and the Pulitzer-nominated play Other Desert Cities (Old Vic, 2014).

The acclaimed novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard has been criticised for exposing the private lives of his family without their knowledge or prior permission in his series of autobiographical books, My Struggle, recently translated into English. Back in 2009, the author AS Byatt launched an attack on writers who combine biography with fiction which she claimed, ‘feels like the appropriation of others’ lives and privacy.’

This theme hits home in the context of Bennett whose elderly mother (played by Gwen Taylor) also appears in the film and is good for a few funny lines. Hytner retains the double-Bennett motif from his theatre production where, for obvious reasons, he cast two actors as Bennett.

Here, Alex Jennings (The Queen, 2006), is terrific playing both Bennett the socially-minded private resident and Bennett the self-serving writer – who bicker lovingly with one another like the proverbial two old ladies.

This double-character motif is awkward on film, and is not entirely successful, but it invites us to reflect on Bennett’s unspoken pact with Miss Shepherd, the cantankerous lady consumed by mental illness in a cruel and wasted life. Shepherd was a promising pianist who might well have become a professional musician in different circumstances and Hytner ensures we are mindful of this tragedy. He gets the balance just right, as the does the magnificent Maggie Smith, between humour (and there are some very funny moments) and pathos while avoiding sentimentality. This is not an easy feat.

Bennett shocked his real-life neighbours by his decision to grant the troubled vagabond a temporary space for her caravan in his driveway. He thought she would stay a few months. She remained for 15 years. She died in 1989, never knowing that their arrangement would add to Bennett’s wealth and fame over the next twenty-five years.