Joyce Glasser reviews The Limehouse Golem (September 1, 2017), Cert. 15, 109 min.

Juan Carlos Medina’s The Limehouse Golem, an adaptation of Peter Ackroyd’s 1994 novel Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem

, might seem like a curious choice for a little known 40-year-old writer/director (Painless, Rage) from Miami, Florida, particularly as the script is by British scriptwriter Jane Goldman, best known for her blockbuster comic book action-fantasy fare (Kingsman: The Secret Service, X-Men: First Class and Kick-Ass). But Goldman also adapted for the screen The Woman in Black, a very English supernatural thriller set in 1889, just eight years after the events in The Limehouse Golem

. Following the recent period, London-set TV series Ripper Street and Taboo, it also feels like an odd choice for a feature film, but that makes The Limehouse Golem

a welcome change from CGI summer fare and formulaic feel-good movies.

A feature of the novel is that the London-centric biographer/novelist Peter Ackroyd mixes real people with fictionalised characters, a feat that adds a touch of authenticity to both the novel and to the film. Dan Leno (Douglas Booth) was a real life music hall comedian and impresario reported to be the richest performer in England at the time. His story overlaps with that of fictionalised orphan Elizabeth Cree (Amelia Crouch). She shows up at his music hall shortly after the death of her mother – a dead-ringer for the abusive, religious fanatic mother in Brian de Palma’s Carrie. There is something decadent and effete about the handsome Leno, but underneath his heavy make-up and frocks is a business man. Struck by the pretty, young girl’s fearless enthusiasm and strength of character, he takes Elizabeth under his wing, much to the consternation of the jealous trapeze artist Aveline Orega (Maria Valverde).

Elizabeth (now played by Olivia Cooke) is a hit with the crowds and attracts the attention of journalist and would-be playwright John Cree (Sam Reid). Cree snubs Aveline after meeting Elizabeth and the vindictive Aveline wants revenge. Elizabeth is attracted not only to the financial security the handsome Cree could offer, but by the status that a part in his long-delayed play would bring. While Elizabeth is by now a music hall star, she longs for recognition as a serious stage actress.

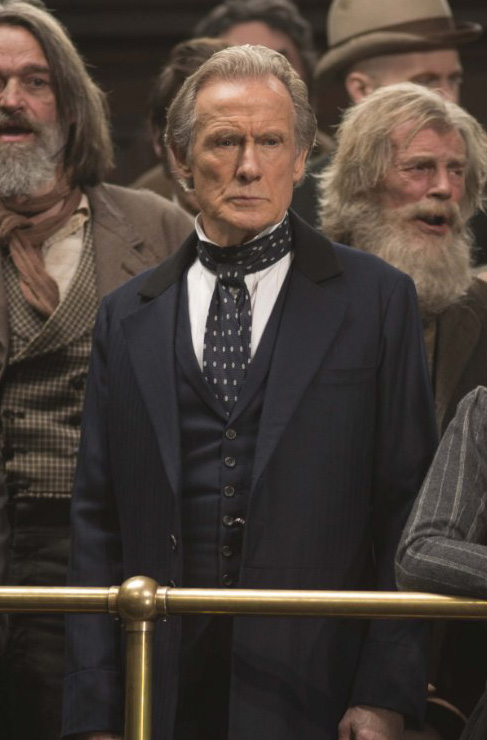

The character that unites the real world of the impoverished Limehouse backstreets with Dan Leno’s world of escapism is Inspector John Kildare (Bill Nighy). In an early scene we see Elizabeth, now Mrs Cree, discovering her husband John’s body in his bed. And just as Elizabeth becomes a suspect in her husband’s poisoning, so Cree himself becomes a suspect in the high-profile Limehouse murders, precursors of the so-called Jack the Ripper murders. If Cree is spared from interrogation by his untimely death, Elizabeth faces the gallows.

One of the problems with adapting an intentionally tricky novel with a complicated plot into a film is that it does not leave much time for character development. While the filmmakers do a good job of dramatising the relationship between the older, educated, but underachieving Scotland Yard inspector with the more detached, working-class sidekick assigned to him (Daniel Mays), there is little room to develop Kildare’s character. It is made clear that he is a scapegoat assigned the thankless task that has eluded more experienced detectives, including his superior who is eager to dump the case on his subordinate.

What makes this case even more challenging is the random nature of the killings. Unlike the Ripper, who only murdered prostitutes, the Limehouse murderer kills prostitutes, maids, families and single, old men alike.

We never learn why this is Kildare’s first murder case and what has held him back in his career, although there are rumours that the bachelor prefers men to women. Kildare is unique in feeling a bond of sympathy with and admiration for suspect Elizabeth Cree because she has overcome adversity to become a well-paid celebrity in her own right. Even if she killed her husband, John, she might have a good reason if he were the serial killer. Meanwhile, the shrewd Elizabeth tells Kildare that he is entitled to his moment of fame (in cracking the case), just as she was.

Kildare’s big breakthrough, a diary of anonymous but incriminating scribbles in a library book, leads Kildare to the British Museum’s Reading Room. He concludes that the names of the readers signed in on a particular day are all suspects worth interviewing. If he can match their handwriting, he may have his killer.

Cree turns out to be dead, but novelist, teacher and social commentator George Gissing (Morgan Watkins), is a likely suspect since in real life the reading room frequenter served a month’s hard labour for stealing from his students, allegedly after bankrupting himself in an attempt to keep a prostitute off the streets. Another suspect is Karl Marx (Henry Goodman) who, seven years earlier wrote Das Kapital in the Reading Room and used the facility until his death in 1883.

There are some wonderful touches to the film, such as Kildare’s first look at the horrific handiwork of the so-called Limehouse Golem (a creature from Jewish folklore in this anti-Semitic period). Kildare has to battle his way through police, the press and also the punters looking for entertainment. In the Georgian era visiting a crime scene became a major pastime for all social classes and some unscrupulous entrepreneurs would charge admission.

While all this is a lot of fun, a story with two major murder cases and so many interesting, if not duplicitous, characters, feels crammed full and rushed. There is no time to savour the plot points, let alone the characters. Bill Nighy is denied the chance to create a rich and complex detective – an alternative to Sherlock Holmes. But the real killer is a film structured around flashbacks, some very long, such as Elizabeth’s childhood; and some short flashes to illustrate a thought process or to provide the audience with another chance of evaluating the evidence. While the film is engrossing from start to finish, the increasingly inevitable flashback tends to break up its tension and flow.

You can watch the film trailer here: