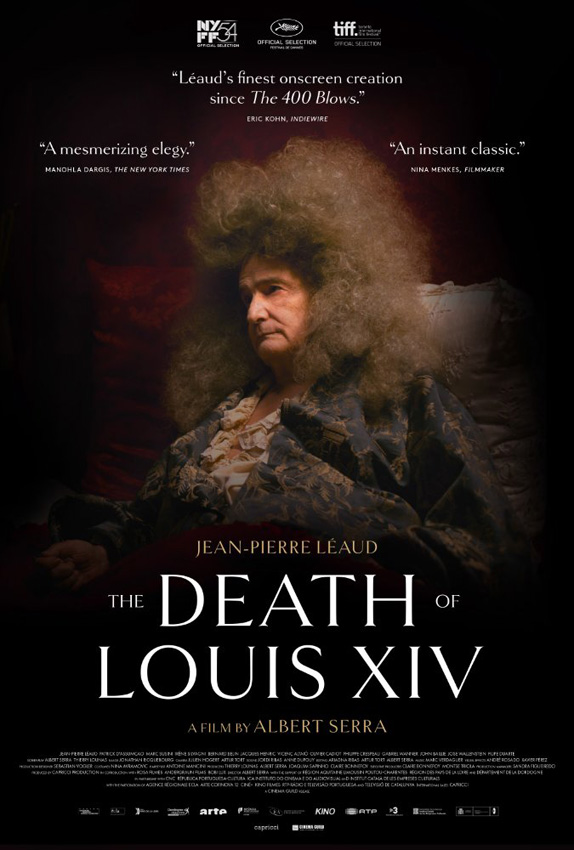

Joyce Glasser reviews The Death of Louis XIV (July 14, 2017) Cert: 12A, 115 mins

From Catalonian co-writer (with Thierry Lounas)/director Albert Serra’s new film, The Death of Louis XIV, set almost entirely in the 76-year-old monarch’s bedroom in Versailles 1715, we can make three observations. First, in chronicling in minute detail, the very human suffering and helpless humiliation of a once mighty warrior, legendary seducer, visionary builder and bon vivant, Serra contextualises the myth of the Sun King. Second, as Chilean filmmaker Pablo Larraín showed with his historical biopic about Kennedy’s widow, Jackie, you do not have to be a French national to make a penetrating yet respectful film about arguably France’s most famous king. And third, a talented filmmaker can make an engrossing and beautiful film without CGI, action sequences, cranes, dollies, sex scenes or even much dialogue. For most of the film, the dying King (played by the Prince of the French New Wave, 73-year-old Jean-Pierre Léaud), is too weak to do more than mumble.

In addition to some effectively used music, however, there is also plenty of sound. The six-person-strong sound department contribute so much to the film without our realising all the work that has gone into. As in Serra’s previous film, The Story of My Death, set in the latter part of the 18th century, birdsong is one of the first sounds we hear, along with the clinking of wheels on a road. Out on a ‘walk’ to admire the landscape, the King feels a pain in his left leg.

In addition to some effectively used music, however, there is also plenty of sound. The six-person-strong sound department contribute so much to the film without our realising all the work that has gone into. As in Serra’s previous film, The Story of My Death, set in the latter part of the 18th century, birdsong is one of the first sounds we hear, along with the clinking of wheels on a road. Out on a ‘walk’ to admire the landscape, the King feels a pain in his left leg.

At first, the pain appears to be no more than sign of old age, and the court applauds the king as he eats an egg and a biscuit and lovingly plays with his beautiful hunting dogs, lamenting that the doctor does not permit him to see them more often. But he has little enthusiasm for a bid to bolster coastal fortifications, even though a consultant from England, the Duke of York, makes a case for cheaper and more resistant stones found at the Nile River. And he declines to join the ladies of the court and tells them he prefers to go to bed. For the remainder of the film he is shown reclining in bed and the sound takes in the shuffling of silk, the crunching of biscuits, the movement of bodies in a confined space, and the king’s breathing.

This is a far cry from the Louis XIV many of today’s television viewers will recognise from the popular series Versailles. But from 1667, when the 28-year-old King Louis XIV becomes de facto ruler of France and commissioned Versailles, Louis suffered from various illnesses, including diabetes, which makes Louis more prone than normal men to the gangrene that killed him. His illnesses were overlooked by the fact that his doctors were largely ignorant and that, despite periodic ailments, he outlived most of his legitimate family. When, in a touching scene, Louis calls in his heir, it is his five-year-old great-grandson, Louis, the Duke of Anjou’s youngest son, to whom he imparts his humbling and uncharacteristic advice. ‘Make peace with your neighbours and give back to God what is given to you.’ He warns him not to follow his great grandfather’s love for building or for making war.

You might not think that a closely cropped procedural of death by gangrene would make for compelling viewing, but this remarkable film will prove you wrong. The authenticity of the historic depiction we are watching comes across so vividly it’s as though we were there among the doctors and valets, and sharing their emotions. Some are fearful of errors made: at one point, a doctor suggests bleeding, the worst thing to do to a patient whose blood is not circulating properly. Others are so obsequious it is difficult to know their feelings. Some, like the king’s principal doctor, Fagon (Patrick d’Assumçao) and his chief valet, Blouin (Marc Susini) look on the king with compassion and even affection. The doctors realise they should have amputated the leg when they first saw the black sores and smelled the stench that nauseates the king himself. They nonetheless are quick to find a scapegoat in a charlatan from Marseille, Le Brun (Vincenc Altaio) who recommends a vile elixir.

But the authentic feeling of the film comes from more than the acting. Serra benefitted from the Mémoires of Saint-Simeon and of Marquis de Dangeau, courtiers who attended the kings last days with the aim of recording even the gruesome details contemporaneously. Moreover, from 1647 to 1711, the three chief physicians to the king, including Fagon, recorded all of his health problems in the Journal de Santé du Roi (Journal of the King’s Health).

Throughout this ordeal, Léaud, three years younger than the king (who died just before his 77th birthday), is impeccable. His gradual decline is handled with such subtlety you forget he is an actor. With one or two exceptions, he reclines in a huge curled wig with a deep part in the middle, but his face and body remain expressive. At one point, he stares at us – or so it seems in Jonathan Ricquebourg’s gorgeous, candle-lit cinematography, for a full three minutes.

In the final scene, a courtier asks Fagon what gangrene is. After a long pause, the exhausted doctor simply says, ‘I don’t know.’ All the money at the king’s disposal could not buy that knowledge. Though they are well aware of their limitations, he adds, ‘Gentlemen, we will do better next time.’

You can watch the film trailer here: