Joyce Glasser reviews Starfish (October 28 2016)

Films about people battling the odds against cancer, from Terms of Endearment to Fault in our Stars to the upcoming weepy A Monster Calls, are good showcases for a film star’s career, but hard-going for the audience. While asking audiences to pay to see a person waste away from cancer is nonetheless a common occurrence, Starfish affords a bigger challenge. It is the first film to depict an even nastier disease that kills more people than bowel, breast, prostate cancer and road accidents combined, and even more randomly.

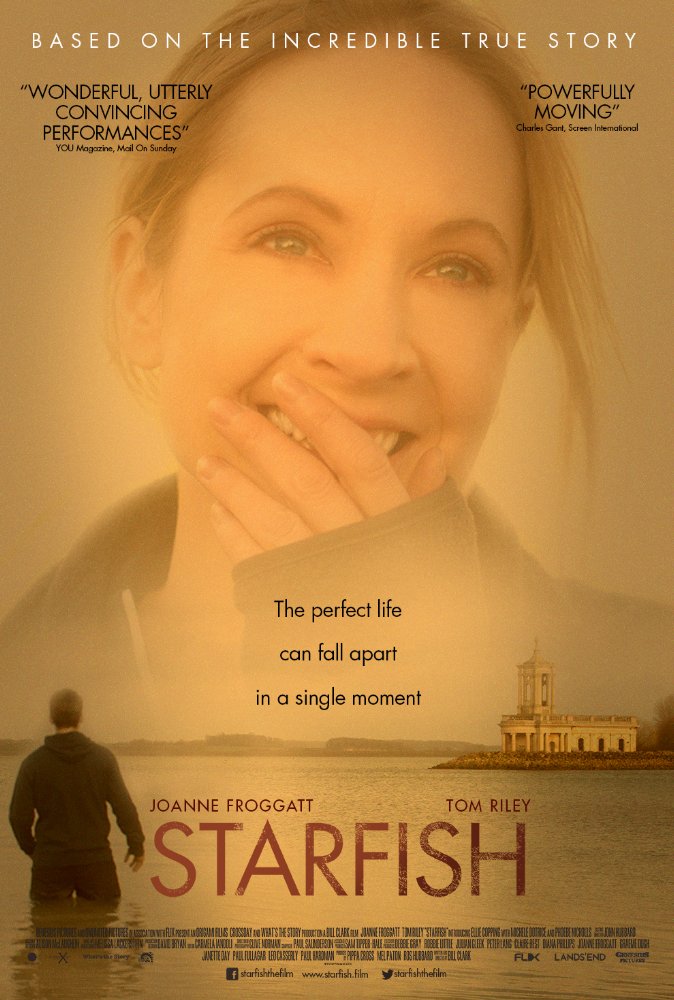

Starfish tells the engrossing true story of East Midlands’ couple Tom and Nicola Ray who knew even less about Sepsis than you might when Tom suffered from what he believed was a stomach ache after eating a sausage. Within days, the frightening diagnosis put an end to their fairy-tale life and the joyous prospects of a second child. East Midlands’ writer/director Bill Clark’s second feature manages to spare us nothing without being maudlin, while leading to a surprisingly uplifting conclusion.

Starfish tells the engrossing true story of East Midlands’ couple Tom and Nicola Ray who knew even less about Sepsis than you might when Tom suffered from what he believed was a stomach ache after eating a sausage. Within days, the frightening diagnosis put an end to their fairy-tale life and the joyous prospects of a second child. East Midlands’ writer/director Bill Clark’s second feature manages to spare us nothing without being maudlin, while leading to a surprisingly uplifting conclusion.

Thirty-something Tom Ray (Tom Riley) is a house husband and budding children’s book author whose artistic wife Nicola (Joanne Frogatt) is the breadwinner, working for a media company. Tom takes their four-year-old daughter Grace (Ellie Coping, in a screen debut) to Rutland Water to fly a kite. That night, in a nice bit of foreshadowing, he tells his adoring daughter about starfish that grow back their arms and legs if they are cut off. Despite learning that starfish need salt water to survive, Grace clings on to the hope that that the land-locked Rutland reservoir might hold some surprises yet.

Pregnant Nicola returns from her last day of work before maternity leave announcing, to Tom’s relief that it makes more sense for her to return to work after the new baby is born. The happiness of that evening changes suddenly when Tom is awakens with a violent stomach ache. Nicola leaves him in bed while she wraps up loose ends at work when she receives Tom’s faint call for help. He is left for hours in a hospital corridor waiting for a doctor and complaining of cold hands and feet.

The next time we see Tom his hands, feet and face are black as if struck with frostbite, and two doctors have informed the bewildered couple that Tom has contracted Sepsis, perhaps from a chest infection. To save Tom’s life, Nicola must sign her permission for amputation of the rotten body parts, and even then there is no guarantee. The loss of four limbs is, even with the possibility of artificial limbs, bad enough, but Nicola buckles when it comes to her handsome husband’s face. Later in the film when Tom is shocked at the sight of the freakish facial reconstruction, the surgeon (David Carr) informs him he is a specialist, but this was his first facial reconstruction.

When Grace first sees her father, his face still mercifully wrapped in bandages, she runs away, saying, ‘that’s not my daddy.’ Nicola realises she has to walk a fine line between the reality of her husband’s disfigurement and his need to recover self-confidence and self-esteem. She begins fund raising for Tom’s medical needs because there is no help from the State. Despite her impressive success, the bills and the stress continue to mount.

Frustrated and angry, Tom begins to see himself alongside his baby son Freddie as a helpless child surrounded by decision-making females. The problem for Nicola is that his fear is a self-fulfilling prophecy. When his generous, self-sacrificing mother-in-law (Michele Dotrice) suggests they sell their lovely, stone cottage and move in to her large nondescript home to save money, Tom is furious and lashes out. When the house is sold, he becomes increasingly bitter about his loss of dignity and manhood. Self-pity and excessive amounts of red wine are natural reactions, but when his negativity and belligerence are directed at an exhausted Nicola, there is a dramatic showdown that scares Tom, who realises he has take Nicola for granted.

An important part of Tom’s story is introduced through flashbacks depicting Tom’s minor celebrity father, a womanizer who deserted the family and remains estranged unwilling to send much need funds. Tom was determined to be a different kind of husband and father, and he has been. When Tom begs Nicola not to leave him, her response, ‘we’re not leaving you, it’s the other way around,’ strikes the chord that eventually helps give Tom a goal and purpose.

As Grace quietly begins removing the salt shaker from the table to scatter salt in the reservoir, a small miracle of a different sort occurs out of the blue. A bullied boy, who once stared at Tom’s deformity, but reminds Tom of his own youth, loses his ball. If the touching ending is over-egged, Clark exercises such restraint elsewhere in the film that you hardly begrudge him this minor – and for many perhaps welcome – indulgence.

This harrowing film succeeds in part because it is, at its core, a love story about life and not about death. But the execution is everything, and credit is due to Clark’s sensitive, well-researched and thoughtfully-written script and the strong, nuanced performances from Frogatt and Ray that always ring true. Indeed it is hard to imagine the results were the actors not up to the task. It must have been daunting for them to act in the presence of the real Tom and Nic who were apparently on the set, particularly when Tom Ray served as a body double for scenes that no amount of CGI could render convincing.

You can watch the film trailer here: