Gunda (June 4, 2021) Cert. PG, 94 mins.

Sixty-year-old Russian director Victor Kossakovsky waited years for producers to finance this deeply affecting masterwork, despite its modest budget. His connection with the subject of his latest documentary, however, goes back even longer – to childhood. The animals that feature in Gunda appear throughout his filmography, but in Gunda they are the stars.

Born and raised in St Petersburg, (then Leningrad) Kossakovsky tells us about a visit to the country that left an impression on him – much like the impression his film might leave on the audience: “I spent some months with relatives in the country, and they had Vasya, a piglet who became my friend, he obviously was an intelligent creature who loved me and whom I loved in return.”

You can see why the film might not have been deemed a commercial proposition, even before Covid-19. Now audiences are cautiously being enticed back to the cinema by big name films, special effects, fiendish plots, plenty of action and all-star casts. In Gunda there are no human beings at all let alone actors – although a farm vehicle in the frame at the end of the film suggests the presence of an off-camera farmer. Shot on monochrome film, there is no dialogue or narration, no captions and no music to tell us how to feel.

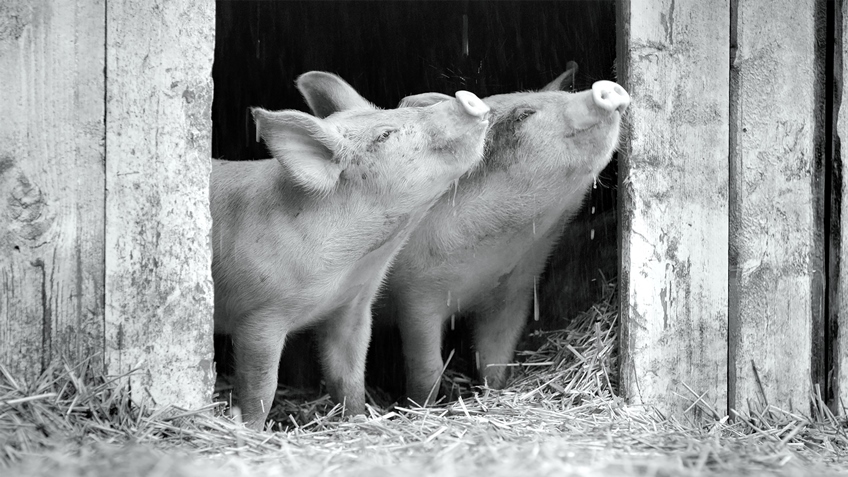

The funny thing is, you will not miss these embellishments when the sound of birdsong is so prevalent and the star is the eponymous heroine, a Norwegian sow. The story begins in a small wooden structure, known as a pigsty, somewhere on a farm. Hay is billowing out of the entrance, a small open door. A huge pig is lying on the hay in the opening, grunting away over the trill. Suddenly, a piglet crawls out of nowhere and slides down the hay, waking the exhausted sow. The grunting intensifies, but there is no use pressing the snooze button. It’s time to get up.

Gunda has just given birth to ten piglets, her needy co-stars. Defeated, she lies down again, and we witness the jockeying for position in the feeding frenzy that follows.

Cut to the piglets huddling together for warmth, as the camera, ingeniously set up to capture the interior of this dark, tiny shed, pans across the straw to reveal the furry runt of the litter, emerging from under the hay.

Sub-plots include a herd of cows galloping joyfully from their barn, and a one-legged rooster cautiously leaving a cage and making its way through the woods, only for them all to be confronted with barbed wire fences. There is a certain tension built up over the unfolding of the rooster’s adventure: will harm come to it; will it make it to freedom?

These animals are given their screen time, and although they do not talk like animated roosters and cows in children’s movies, somehow, they communicate with us through the director’s respectful and compassionate lens. Kossakovsky wants us to look into a cow’s eyes and see its soul.

Kossakovsky, who derides didactic films, leaves us alone to observe and intuitively come up with our own thoughts about these animals. Perhaps at some point you might wonder if the cow who stops in the far corner of the field and stares into the camera is an old cow. How long has it been running out of that barn into that field, only to realise there is nowhere to go? Cows, we learn in the production notes, have a natural lifespan of ten to twenty years. There are some 1.5 billion cows in the world right now that will not live past their second birthdays. Fifty-billion chickens each year will not live to be one year old, and, as we saw in the film Minari, billions of male chicks are incinerated at birth.

Less subtle than Kossakovsky, at his Best Actor acceptance speech for The Joker at the 2020 Academy Awards, Joaquin Phoenix included animal rights in his speech. He mentioned race and gender inequality as you would expect, but he then railed against the fundamental inequality of one species dominating the other over which it has no rights. Phoenix is not just blasting hot air before an influential audience and millions of television viewers. He is an Executive Producer on this film.

Patient with her demanding off-spring, yet firm, Gunda allows herself some private time, venturing out beyond the range of the piglets to forage for food while they learn to dig closer to home. Most pigs are not so lucky, living on concrete in huge barns. Gunda is allowed to dig in the soil under the open sky and cool off in a muddy ditch, but she is being used by both the farmers for bacon and by her demanding piglets, for which she is a milk-machine.

The last ten minutes of the film might just be the more devastating of any feature this year if not the most dramatic. Yet, like the 19th century animal painter Rosa Bonheur, Kossakovsky refuses to sentimentalise, romanticise or anthropomorphise his animals, allowing us to observe them anew and perhaps, for the first time.