The election of the new President of the USA has sent shock waves throughout the West including those concerned with military defence and security. Mr Trump has been quite vociferous regarding his country’s contribution to NATO and with the uncertainty of Brexit and the threat of Russia’s posturing keeping the peace has become a much discussed topic.

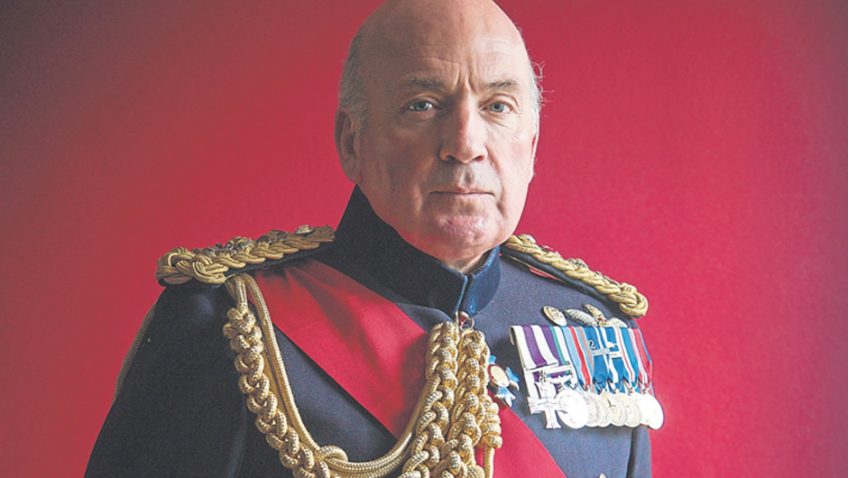

One man who is worth listening to as an authority on all matters military is General Lord Richard Dannatt, an ex-Chief of General Staff. Feeling slightly ignorant and in awe of the high-ranking officer I was put at ease by his courteous and patient manner when I put my questions to him on Armistice Day. Speaking from his home office and happy to explain the structure of our defence policy, I learn much from his clarification.

I am now much clearer on the roles of the United Nations and NATO and the large part that British Forces play on the world stage. His recent book Boots on the Ground details the army’s involvement in war and peace since 1945 and makes fascinating reading. From our country’s part in the Second World War to the present day, the different functions of battles make more sense. The deployment of troops to protect Aden (now Yemen) where my husband was stationed, was the last hoorah of the Empire and in 1967, due to lack of funds, Britain withdrew from the country and left them to their own devices.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), was formed in 1949 partly as a re-action to the cold war and in a broader effort to serve three purposes: deterring Soviet expansionism, forbidding the revival of nationalist militarism in Europe through a strong North American presence on the continent, and encouraging European political integration.

Most action now seen by the Army is at the behest of NATO under orders from the UN as part of a combined force. The first of such wars was in 1950 when troops were sent to Korea as part of a joint operation.

I asked the General what would be his view had we been pressured into forming a European combined force such as was suggested by other members of the EU. He was vehemently opposed to any such organisation as integration with other less efficient forces would be a recipe for disaster. Our troops are some of the best in the world and can operate under the orders of NATO. His pride in the British Army is obvious.

It is also apparent that the welfare of servicemen and women is high priority. When I asked his opinion on women fighting on the front line he was quite clear that while he did not object to them provided they were physically fit enough, he expressed the sentiment that killing people is not women’s work; or men’s for that matter.

While he is adamant that the three services that make up our military capability should remain separate he explained that many joint operations involve Army, Navy and RAF. They, for example, share the helicopter unit, to help keep the defence budget down. Having to fight for enough funding to equip our forces is a battle of its own with the Government and Public Accounts committee. The General explained that the Army wants the best like any other organisation, and cutting edge technology is not cheap.

It is the battle for his troops that is most important and he was instrumental in helping to form the charity Help for Heroes which has brought the plight of soldiers firmly to the public attention. “Apart from last year, 1968 was the only year that no-one was killed on the battlefield and conflicts continue all over the globe. If we are to protect our security, we must also be prepared to value the lives of those who fight on our behalf” he told me. “Often stress disorders do not manifest themselves until up to 12 years after involvement and as a nation we must be prepared to care for and help these men and women”.

To learn more about the man and his work you can read two books, his autobiography Leading from the Front and A History of the Army since 1945 Boots on the Ground.