Joyce Glasser reviews The Electrical Life of Louis Wain (January 1, 2022) Cert 12A, 111 mins.

British audiences going to the “pictures” in 1921 might see a British Pathé newsreel beginning with the subtitle: “There is hardly a child or adult in the Empire who does not know Mr. Wain’s friends.” Part of a series entitled Celebrities at Home, the newsreel shows the famous Mr Wain drawing his “friends”: a series of cats. Today, only a handful of private art collectors and archivists in UK mental health institutions know of Louis Wain’s celebrity. Director Will Sharpe’s (Flowers, Landscapers) The Electrical Life of Louis Wain is out to change that with a frustrating but entertaining biopic that immerses us in Wain’s private world.

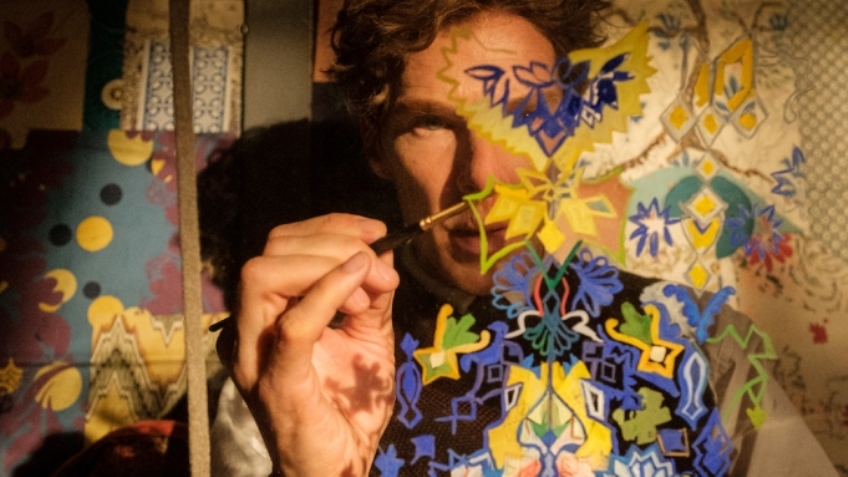

Wain (a moustached, harelipped, Benedict Cumberbatch), an awkward, eccentric, brilliant illustrator and would-be inventor, could draw as quickly and accurately as a photographer could adjust his lens, but prefers animals to humans. This is brought into focus in the first scenes as he informs Dan Rider (Adeel Akhtar), a book seller he meets on a train, when he agrees to sketch Rider’s dog for free. When Wain arrives at the offices of Illustrated London News with his commissions from a country fair, he is wounded and muddy, but produces an astonishing sketch of the charging bull.

The 1880s is a period of invention and discovery and Wain wants to be an artist, write an opera and develop his inventions. When his father, a traveling textile salesman, dies, Louis, aged 20, struggles to support his ailing mother and five sisters. The women cling to their respectability and class status despite Wain’s inability to negotiate a salary commensurate with his talent.

When the family hire a live-in governess, Emily Richardson (Claire Foy), Louis offers to tutor his sisters to save the expense – until he falls in love with her. In a charming dinner scene, the two lock eyes and their fate is sealed, much to the horror of eldest sister Caroline (Andrea Riseborough). Emily is, after all, ten years her brother’s senior and a lowly governess. As Olivia Colman’s supercilious and redundant narration (over visuals showing the same thing), tells us, the Wains live in a gossipy, judgmental society and the sisters always blame Wain’s scandalous marriage for their inability to find husbands. Emily, however, was the catalyst for Louis’s cats.

The film is delightfully romantic in the courtship and subsequent marriage of the star-crossed lovers. Cumberbatch and Foy work so convincingly together that the rest of the film never reaches the same level of charm or intensity.

The newlyweds move into a fairy-tale garden cottage that looks like it is in the country, but was actually in today’s Belsize Park, London. It is there that they “adopt” a stray kitten that is named Peter and becomes the child they never had. Peter is to keep Emily company when she is diagnosed with cancer shortly after the marriage.

Louis paints Peter from every angle and although he preferred dogs, rabbits, fish and birds to cats, with Emily’s encouragement, he shows the cats to his then boss, Sir William Ingram, (Toby Jones). The publisher is astute enough to see their entertainment and novelty value for a special Christmas issue, and, in 1884, Louis Wain’s cats are published in the Illustrated London News.

It is a year after Emily’s tragic death in 1887, however, that Wain begins seeing cats instead of people at home and at leisure and produces his anthropomorphised cats. Whether Wain was the man who introduced the idea of cats as pets to the UK, it is a fact that in the late 1880s, they were not popular. Acclaimed as an authority on cats, “The Hogarth of Cat Life” (as the editor of Punch called him) is, as we see in the film, made President of the newly formed National Cat Club.

In the mid-1890s, with Wain struggling to live on his own, Sir William brings about a reconciliation with his sisters and provides the family with a large, elegant seaside villa in Westgate. It is here, however, that youngest sister, Marie (Hayley Squires) who suffers from delusions, is sent to a private mental home aged 29. Sir William seems to care about Wain, but we never learn why he underpays him and fails to ensure that Wain’s private work was copyrighted. This failure to earn royalties means Wain and his family often lived in poverty despite his fame and success.

Against his doctor’s advice, Wain, who is becoming disruptive and delusional, accepts an invitation from publishing mogul William Randolph Hearst to travel to America for a comic strip column. Louise’s odd theories on cats, however, are one of a number of signs that Wain has mental health issues. He proposes that the cat has its own compass that is sent through the electrical strength of its fur – being governed by the negative and positive poles of the earth, and that it washes itself to complete an electrical circuit. With the news of his mother’s death, he reluctantly returns to England, apparently without an American contract.

Sharpe, who has a personal interest in eccentrics and mental health issues, was behind the Channel 4 series Flowers, a British black comedy sitcom about an eccentric family co-starring Colman. Co-writing with Simon Stephenson, Sharpe has ingeniously merged form and content with a visually kaleidoscopic and mind-bending style to tell this tragic tale.

If you go to an exhibition at the Bethlem Mental Hospital’s Museum of the Mind, mounted to coincide with the film, you will see how Sharpe has used the often-overwrought colours and fantasied landscapes of the paintings in his film. The storybook cottage where Emily and Wain are so happy is inspired by the paintings.

Dan Rider discovers Wain in a pauper’s institution and sets up an Appeal Committee. With the help of H.G. Wells, whose speech is reproduced at the beginning of the film, and Prime Minister Ramsey Macdonald, enough money is raised to move Wain to the more upmarket Royal Bethlem Hospital (now in Beckenham). Here, and at Napsbury Hospital where he dies in 1939, Wain’s cats become increasingly abstract as though truly electrified. In several paintings the cats dissolve into the carpet, bringing to mind his family’s profession.

Sharpe’s clever visual strategy of showing us the world through Wain’s eyes along with Cumberbatch’s terrific performance are, regrettably, compromised by an overdose of whimsy and the distracting, jarring narration that tries to turn a tragic story into a very British comedy.