Ailey (January 7th) Cert 12A, 90 mins

Jamila Wignot’s poetic and visually melodious and informative documentary on a candidate for the most important cultural icon of the 20th century, begins with a star-studded tribute hosted by President Ronald Reagan. It takes place at the Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts, where Alvin Ailey, raised in poverty in racist, depression-era Texas, is awarded the nation’s highest distinction for Lifetime Contributions to American Culture through the Performing Arts.

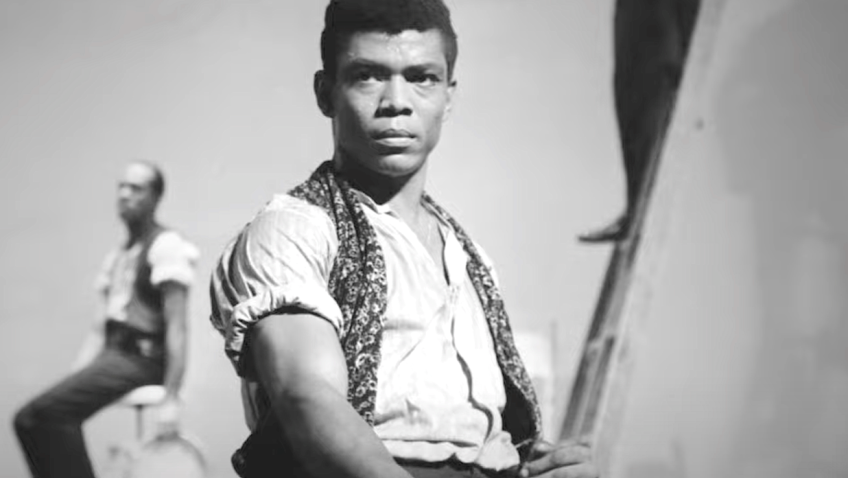

The prematurely frail 58-year-old still retains the dignified grace of the handsome, strong, athletic and elegant dancer many fortunate people over 60 had the luck to see in person. He beams a warm smile to the dancers on stage who bow to him and the cheering audience, and he bows back to them. They have preformed part of his early (1960) masterpiece, Revelations, recognised as one of the most popular and performed ballets in the world. Ailey would die the following year of Aids.

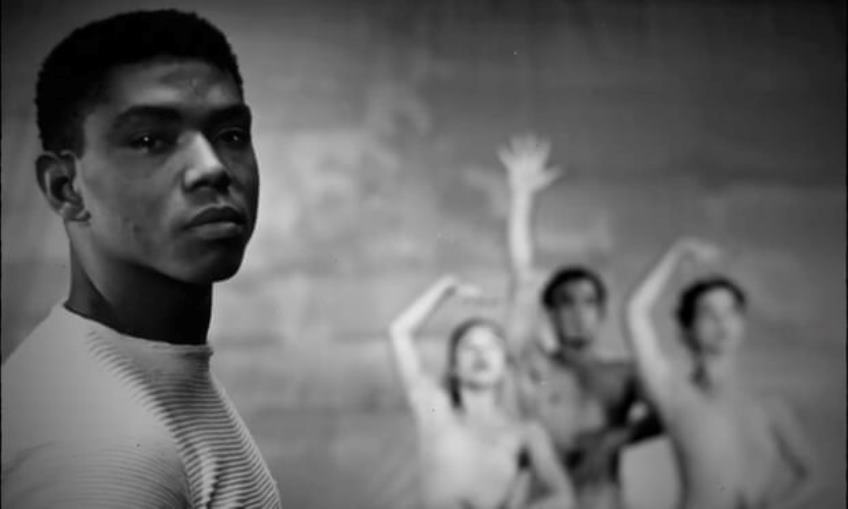

Wignot contrasts Ailey’s humble beginnings, traipsing across segregated, racist Texas on the hip of his teenage, single mother and working in the cotton fields and scrubbing white family’s floors, with the glowing, multi-storied, Manhattan building bearing the name Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT). Inside, choreographer Rennie Harris, who is black, is creating a dance, fittingly entitled, Lazarus, for the company’s 60th anniversary.

Ailey retains some good memories of those early days in Texas. The sunsets and running through the fields with his best friend (his first love, perhaps) named Chancy Green, who once saved him from drowning. He loved the gospel music at church and watching the black workers dance at every opportunity.

Ailey’s mother Lula (he never knew his father) brought them to LA for a better life when he was 14. There he saw his first ballet, the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo, on a school trip when he was 15, which thrilled him, but did not inspire him. It was only when Carmen De Lavallade, who noticed his talent, persuaded him to study with Lester Horton (a pioneer in Native American dance) that he began to take dance seriously. He started to dance professionally at 19, and appeared in several films, but never felt he was expressing “the beautiful things inside me.”

Ailey founded his own company at age 27 in 1958 to honour black culture through dance – just three years after Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat for a white bus passenger. A trailblazer in putting black talent, black music and black history on white stages and making identity a theme of his oeuvre, Ailey eventually integrated the company and showcased other choreographers.

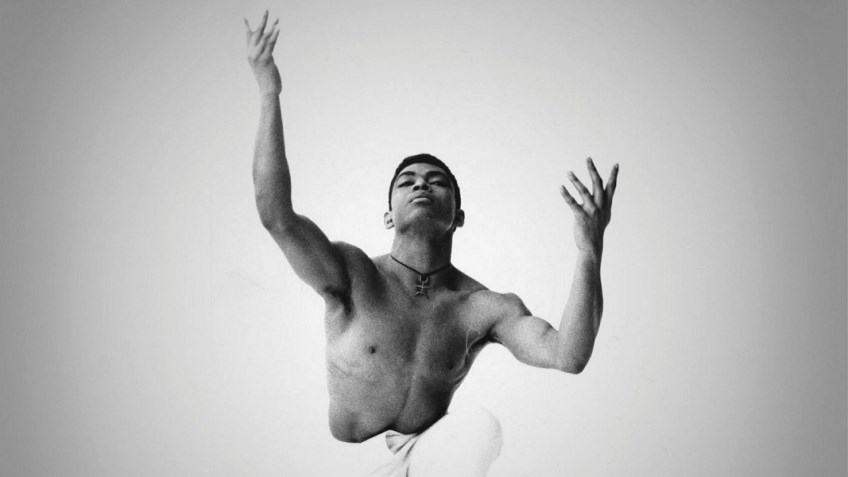

In addition to the heart-rending excerpts from a candid and revealing interview Ailey gave just before his death and moving insights and memories from members of the company, the film is illustrated with glorious, generous clips from Ailey’s dancing and choreographed hits in chronological order. Blues Suite, the ballet that launched his Dance Theatre in 1958 when he was 27; The River (1970), Night Creature (1975), Flowers (1971) and especially Cry (1971), a powerful dance dedicated to “black women everywhere and especially our mothers” for his mother’s birthday.

The three-part ballet, set to popular and gospel music by Alice Coltrane, Laura Nyro and Chuck Griffin, depicts a woman’s journey through slavery to an ecstatic state of grace. The amazing Judith Jamison (who due to her height, shape and colour had trouble finding work) had never danced the entire three-part ballet straight through in rehearsals. At the end, her costume was dripping with sweat. The audience began applauding their support as one cheers on marathon runners.

The paradox is that while Ailey is the ultimate underdog-success story, he could never reconcile “the agony of where I came from and then dancing on the Champs Elysees” with the feeling that you are a “nobody, nothing and on the other hand you are the king.” Until the 1970s, most of his acclaim and much of the applause came from the many government-sponsored foreign tours (the most successful was in the Soviet Union) due to racism in the USA. He objected to the State Department advertising the tours as “ethnic dance” and wanted it changed to “modern dance.” The tours were followed by the CIA.

If race was a challenge, so too, was his homosexuality (he was under surveillance by the CIA for this “crime”). Ailey was very private about his life and never spoke of his sexuality. In the interviews with the dancers, we hear about his inability to form close attachments, other than with his mother, although the AAADT staff and dancers were a close-knit family. But the difficulty of forming attachments was further impeded by his gruelling schedule of travelling half the year and, when in New York, at the theatre in the evenings.

In 1980, after a failed romantic relationship described in the film, the death of his friend Joyce Trisler (for whom he creates the dance, Memoria of 1979), coupled with heavy drinking and a cocaine habit, Ailey suffered a mental breakdown in 1980. Jamison took over the running of the company until his brief return before his early death.

Though no mother should outlive their child, Lula lived to see the impossible made possible by her own son.

Ailey opens in cinemas on 7 January. There will be a special Q & A with Bonnie Greer in cinemas on 4 January 2022. For tickets follow this link.