Joyce Glasser reviews Suspiria (November 16, 2018), Cert. 18, 153 min.

‘There are two things that dance can never be again: Beautiful and cheerful’, Madame Blanc (Tilda Swinton) tells novice recruit Susie Bannion (Dakota Johnson, Bad Times at the El Royale, A Bigger Splash) in a private dance lesson. ‘Today we need to break the nose of every beautiful thing.’ If this isn’t what you would expect from the choreographer of a Pina Bausch-type modern dance company, Madame Blanc is no ordinary choreographer; and the Helena Markos Dance Company is no ordinary company. There are ‘feel good’ movies and ‘feel bad’ movies, and Suspiria, whether to its credit or not, will leave you in a rotten mood.

Italian horror film supremo Dario Argento’s neon-bright, lurid and wild supernatural horror film Suspiria was released in 1977. While it’s on very few lists of the top 500 best films, it captured the imagination of 14-year-old Luca Guadagnino, the future director of I am Love, A Bigger Splash and the acclaimed Call Me by Your Name. Quadagnino’s follow-up, Suspiria, which is Latin for Sighs from the Depths, is far from a straight-forward remake and is very different from Call Me by Your Name.

Italian horror film supremo Dario Argento’s neon-bright, lurid and wild supernatural horror film Suspiria was released in 1977. While it’s on very few lists of the top 500 best films, it captured the imagination of 14-year-old Luca Guadagnino, the future director of I am Love, A Bigger Splash and the acclaimed Call Me by Your Name. Quadagnino’s follow-up, Suspiria, which is Latin for Sighs from the Depths, is far from a straight-forward remake and is very different from Call Me by Your Name.

For one thing it features an (almost) all female cast and is set in a wintery, divided Berlin, 1977 (the date of the original’s release). It is beautifully shot by Sayombhu Mukdeeprom (Call Me by Your Name) in muted colours with stark, dark interiors and frost on the windows. When colour is brought in, such as the lurid, cut-away red costumes in the big public dance performance, you take notice.

It is to this unprepossessing environment that naïve American Susie Bannion travels, happy to escape her strict, Mennonite family in Ohio after her creepy mother’s death. Mum senses that there is evil lurking within her pretty daughter, but it can be shrugged off as the typical stain of original sin the farmer’s wife sees in everyone.

Susie has come to audition for the Helena Markos Dance Company, with no intention of returning home. She is hardly bothered that the female dancers must live (without a young man in sight) in a dormitory attached to the stark, Soviet-modernist building overlooking the Berlin wall which also houses the rehearsal space, theatre and many secret rooms.

Although Susie seems green and has little professional training, she is somehow confident, and talented enough to impress the school’s legendary choreographer Madame Blanc. In fact, the two start to bond into something that feels personal. We hear snippets of conversations throughout the film about a girl ‘being ready’ and Madame Blanc regretting that a great dancer will have so little time to perform.

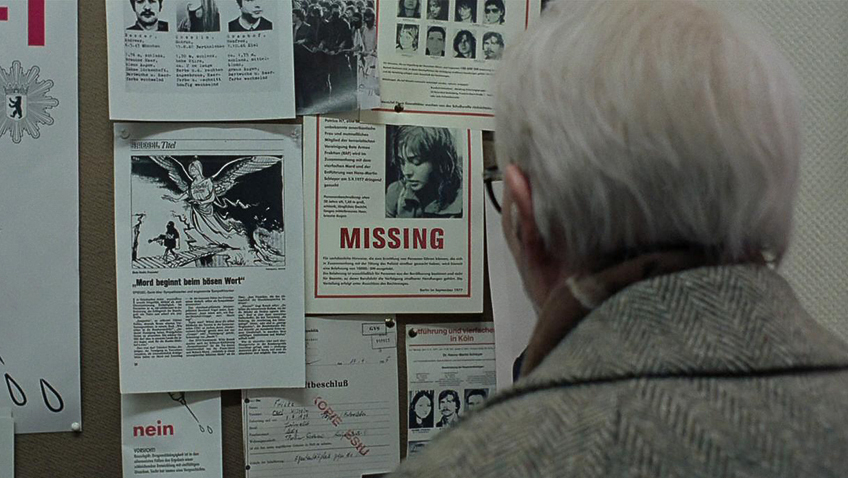

Susie gets her first big break in circumstances that elude her. In another part of the frozen, dark city, an hysterical young woman named Patricia (Chloë Grace Moretz, The Miseducation of Cameron Post, Let Me In) seeks shelter and help from psychiatrist Dr. Josef Klemperer (rather pointlessly played by Tilda Swinton, in prosthetics that are so good you could never suspect it is her). Klemperer is still traumatised by WWII and grieving over his wife, Anke (played by the co-star of the 1977 film, Jessica Harper) who disappeared, and might have died in a concentration camp. Klemperer believes Patricia’s murmurings about witches and odd behaviour are delusional and makes a note in his file, but Patricia disappears, never to return. Concerned, the doctor visits the police, and, in one of the two most chilling scenes in the film, the two male detectives are warmly received by the duplicitous staff.

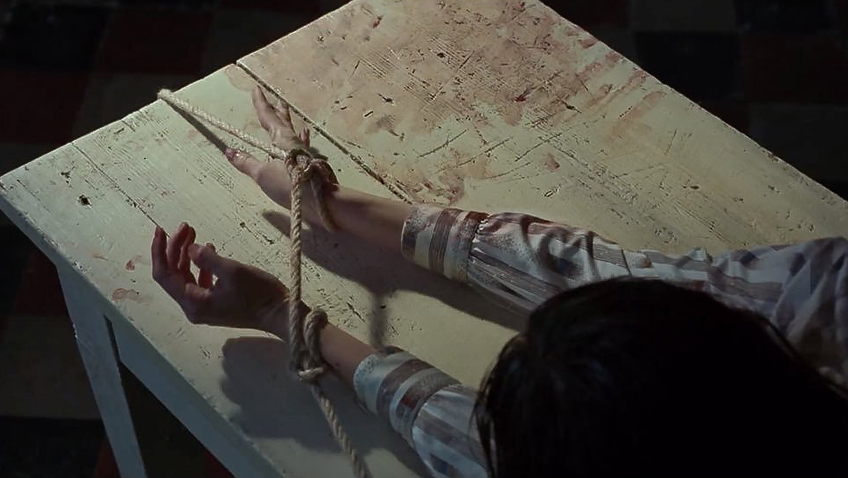

Meanwhile, back in the studio, Susie has been rapidly promoted to lead dancer, replacing Patricia. This promotion that has a knock-on effect on Olga (Russian dance star Elena Fokina), but her angry protests are not welcomed by the teachers and administrators. While Susie, barefoot and feral, is impressing Madame Blanc with her jerky, decisive and violent movements, Olga is taken to a secret studio where she finds herself trapped in a grotesque dance to the death. She ricochets from the mirrors to the dance floor where her limbs wind around her body like a wooden doll being dismantled to fit into a suitcase. Quadagnino’s regular editor Walter Fasano cuts between the dancers with thrilling aplomb and gusto.

Radiohead’s Thom Yorke provides the unsettling music in what is his first solo soundtrack for a feature film, but will probably not be his last. Olga’s dance is, it is fair to say, her last, but, if you are interested, you’ll have to see the film to learn what happens to Madame Blanc, Susie and her new best friend Sara (Mia Goth).

Sara’s subplot is worth our attention as it provides the tension that is felt when the insular world of the academy meets with the outside world. Sara takes a big risk by looking for her friend Patricia, but when she meets with the doctor over tea, she is defensive, refusing to believe the worst about the dance company and to cooperate with him. Here is a rare opportunity for audience involvement, as you feel frustrated when she abruptly leaves the meeting and want to call her back.

Of course anyone in their right mind would quickly recognise that all is not well at this sinister school, but Susie, who experiences firsthand evidence of something disturbing when she witnesses the fate of a policeman, seems unperturbed and wilfully oblivious. Far from feeling uncomfortable, she feels at home at the school.

The set design, the music and the cinematography create an ominous atmosphere to be sure, but the film is more grotesque than scary. The subplot with Dr Klemperer and his wife seems superimposed from another film. It is superfluous, as apart from the interesting suggestion that supernatural forces wipe clean men’s memories, the two eras and two strands never merge. Nor is it clear what the film is saying about dance as an art form.

As for this being a film about female empowerment Guadagnino has worked with Johnson and his muse, Swinton, before and here gives her three roles, two in prosthetics. But evil, manipulative witches are a male construct to appropriate blame and predetermine the fate of male protagonists (Shakespeare exploits this notion in Macbeth). The school’s faculty are older creatures and the derogatory term ‘old hag’ seems to apply. Female empowerment? Female degradation is more like it.

You can watch the film trailer here: