Joyce Glasser reviews Beautiful Boy (January 18, 2019), Cert. 15, 120 min.

Beautiful Boy is director Felix van Groeningen’s first English language feature, but of those he has made in Flemish one is about a romance between a prostitute and a drug dealer; and another is a semi-autobiographical film about a bright boy from a family of alcoholics and misfits who wants to be a writer. If you put that boy into a well-adjusted, loving family and comfortable middle class home and make the boy a drug addict, you have the basics of the heart-breaking, but familiar true story behind Beautiful Boy

.

The film is adapted by Luke Davies (Lion, Candy) from New York Times journalist David Sheff’s best-selling book Beautiful Boy: A Father’s Journey through his Son’s Addiction

; and Tweak: Growing up on Crystal Meth

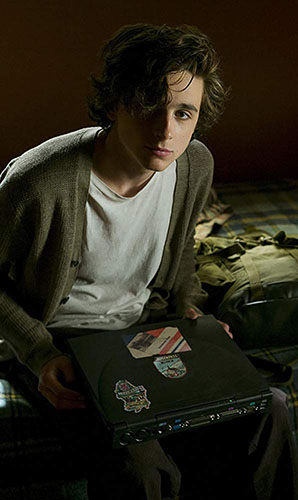

by Nic Sheff, David’s addicted son, both published in 2008. Groeningen and Davies merge the two perspectives, though giving far more weight to David’s book, when it might have been more effective to narrow the focus on either the father or – as Davies did in the script Candy – on the addict. But when the father is Steve Carell (Battle of the Sexes, Foxcatcher) and the son is 23-year-old Oscar-nominated Timothée Chalamet (Call Me by Your Name) it is compelling to have them both.

The film opens with David Sheff (Carell) seated opposite a doctor, who asks him if the information he wants is for the New York Times Magazine.

‘No,’ David, admits, ‘this is a personal matter: it’s about my son. There are moments I look at this kid who I raised and I don’t know who he is. He’s into all sorts of drugs, especially crystal meth which is, I think, the worst. I want to know everything about it – know your enemy. What is it doing to him; what can I do to help him?’

While David becomes an expert on methamphetamine (and learn a few things, too), knowing what to do to help Nic proves far more elusive.

A caption sends us back one year when David is calling the police about his missing son. ‘He’s 18, 130 pounds, 6 feet tall with green eyes and shoulder length brown hair’ – and surprisingly, Nic’s good looks remain after years of drug abuse. David calls his former wife, Vicki (Amy Ryan), who believes the disappearance is related to Nic’s upcoming trip to LA where Vicki now lives. As they argue we imagine that Nic grew up listening to that and perhaps feeling responsible for the divorce. Or is that too simplistic?

When Nic returns home David wants to take him to a drug clinic, but Nick resists. ‘Just hear what they have to say,’ David pleads, and Nic agrees for his dad’s sake.

The advisor tells David that Nic needs immediate treatment because of the level of drugs in his system and the fact that he is in denial. In response to David’s question about his success rate, the doctor says: high end, 80%; low end 25%.

But as David, who is footing the bill for this rehab, learns, the low end is meaningless if Nic walks out of the rehab centre before undergoing treatment.

David feels responsible for introducing Nic to drugs and, in a flashback we see father and son bonding over a celebratory joint. What’s a one-off bit of harmless weed to a high school graduate with the discipline to excel at everything? Nic has applied to six top US universities and has been admitted to all of them.

How can a father watch a son throw away all that potential? When John Lennon wrote the eponymous song, his son’s life was unlived and unblemished.

As painful as it is to extend a helping hand and helplessly watch it come to nothing, the hardest part for David is to break the co-dependency by letting Nic figure things out for himself – or not. And there will be many parents in the audience nodding their heads because while every son or daughter is unique, drug addiction strips them of that individuality and makes them society’s problem as well as the family’s.

Everything about drug addiction is a cliché, but the clichés (which include Nic’s lying and stealing from his own father) are real. It is to the filmmakers’ credit that Beautiful Boy is so absorbing despite the repetition and inevitability of the outcome. In forcing the audience to share the exhausting cycle of hopes being raised and dashed with each admittance to rehab, the filmmakers involve us in David’s agony. We watch Nic grow progressively distant from his family until he becomes an intruder barred from his home for the sake of his step-mother and siblings.

What is missing is more of Nic’s memoir, ‘Tweak’ to help us get inside Nic’s mind and appreciate the magnitude of the tug of war that David is losing.

While the film does reveal Nic’s life away from home, it feels sanitised as though the filmmakers were mindful of the target audience. Nic’s book is far more frank about the sordidness of his drug habit, his sexual encounters and criminal activity than is the film – even when we see the emaciated Nic (Chalamet, of slight build, lost a lot of weight for the part) overdosing and collapsing alone on a filthy floor.

Aspects of Nic’s memoir are revealing, but are not explored in the film which is more focused on David. We discover, for example, that Nic was addicted to alcohol from his first drink as a kid (a fact David did not know when he offered him that harmless joint). A whole new perspective opens up when he suggests that his studies fed into his habit through a romantic notion gleaned from reading writers like Baudelaire and Rimbaud: “Somehow the idea of being this drug-fuelled, outsider artist has always been really appealing to me.”

In the film, one scene in particular stands out for the way it disturbs us on a visceral level in the way that others do not. A guarded but ever hopeful David meets Nic, whom he has not seen in months, for lunch at a depressing restaurant Nic makes it clear he does not have much time, and David, disappointed, begs Nic to at least have a decent lunch. But it is not food that Nic craves. Before our eyes he begins exhibiting withdrawal symptoms, becoming impatient and aggressive. Chalamet is transformed. David realises that he is nothing to Nic anymore but a cash machine. It’s a devastating scene that resonates.

You can watch the film trailer here: