Joyce Glasser reviews Lisetta Carmi: Identities (until 17 December 2023)

Exhibition at the Estorick Collection, London: estorickcollection.com

Lisetta Carmi, who died last year at the age of 98 in Cisternino, Puglia, took some great photographs, but was not a great photographer. She was, however, an important one. The exhibition at the Estorick Collection, the first of her work in the UK, is particularly timely and topical today when antisemitism is rife, Jews are again under threat and in many countries homosexual and transgender people also fear for their lives.

Carmi, born into a middle-class Jewish family in Genoa in 1924, did not set out to be a photographer, and never went to school to study it. Until the age of 14, when she was forced out of school by Italy’s Fascist regime in 1938, she had been studying music at the conservatory in Genoa. This was the year Mussolini declared Judaism “an irreconcilable enemy of Fascism” and his supporter, the ex-patriate poet Ezra Pound’s vile antisemitism deepened. Carmi’s parents saw the writing on the wall and fled on foot to Switzerland where she continued to focus on music.

Upon her return to Genoa she enjoyed a career as a concern pianist. Then in 1960 everything changed. During a June 1960 General Strike Carmi wanted to join the picket lines against the ruling neo-Fascist party. Her teacher warned her against participating in case she damaged her hands. She declared that her hands were less important than humanity and joined the strike.

In 1965, Carmi accompanied a Jewish musicologist friend, Leo Levi, on a research trip and she brought a cheap camera with her to take photos. Her friends reacted positively and gave her confidence. She stopped playing piano and took up photography because, ‘I was interested in people, the lives of human beings, especially the poor.’ She wanted to give a voice to the voiceless.

After working as a stills photographer in a theatre in Bologna, Carmi, now 42, accepted a commission by Cgil, the Italian General Confederation of Labor, to capture (in black and white) the dock workers in Genoa with a socio-political agenda. She also travelled to Sardinia and chronicled the first women employed in the monotonous cork industry on the island. Nowadays, cork trinkets made from the central Sardinia’s cork oaks are geared at tourists, but in the 1960s, they were used in industry. The Sardinian photos, at least those at the Estorick, are less successful than the dock workers. Some of them could do with more detailed commentary so that we know what the work entailed and what we are looking at.

The Estorick’s selection of dock photos, needs no such commentary. Carmi focused on the machinery with as few people as possible to show a metal jungle more than a concrete one. The dangerous conditions of steelworks, and the dock workers dwarfed by the ships and cargoes, are perhaps captured in a photo of a slim worker precariously balancing on the rim of a wide boat in the harbour.

The photos of the labour intensive work loading toxic cargos from the container ships remind us that these tasks are now mainly assumed by robots. We see one shirtless man, dramatically shot from above, as if he is an actor in Eugene O’Neill’s 1922 expressionist anti-capitalist play, The Hairy Ape, one of the only American plays celebrated in Lenin’s Russia and produced there from the mid-1920s.

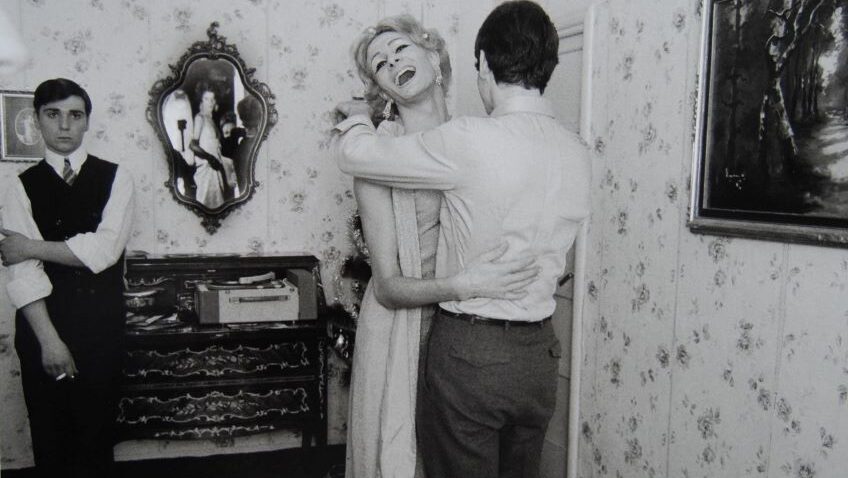

If Carmi felt compassion for poor people, she felt a connection to those rejected by society and marginalised. In the second room of the exhibition we see a selection of the photos she is perhaps best known for: her photos of the transgender community in the Via del Campo district of Genoa. Before the transvestites gravitated to the district in the 1960s and ‘70s, it had been the Jewish ghetto.

In the selection at the Estorick, and in her famous book I Travestiti, published in 1972, we see a colour photo of three transgender women on the steps of a rundown, depressing building. A pile of cigarettes is clearly visible on the pavement, with one of the three adding to the outdoor ashtray. In another, an emaciated transgender prostitute sits on a rickety chair outside a house with a cracked wall, propositioning a passing sailor. Opposite in the alleyway, a business man carrying a heavy suitcase, looks on.

These are the best of the series. The more static, posed “beauty” shots of the transgender women on their beds or posing in close up, are less interesting to us now. But for the community, they were a way of being acknowledged as human beings in the bodies they identified with, and she gave them the portraits as gifts. For Carmi, the trust she earned to spend time amongst them was a gift. ‘Thanks to them, I learned to accept myself.’ Rejecting marriage and the traditional roles assigned to women at the time, Carmi was fighting not just for social justice, but for ‘the right that we all have to determine our own identity.’

Carmi did not operate in a vacuum. Both her parents were amateur photographers and her brother Eugenio was a painter. She was part of a post-war artistic community and her photos illustrated a book by the great political author Leonardo Sciascia. Eugenio Carmi likewise collaborated with his friend Umberto Eco, including on The Three Astronauts, a book capitalising on the US and Russian space races to imagine a space landing that fostered peace beyond borders. Eugenio and Umberto died within three days of one another in 2016.

There is a kind of irony or poetic justice that arguably Carmi’s greatest achievement, were her portraits of Ezra Pound, shot on a Leica 35mm camera. On February 11, 1966, the poet shuffled in his bathrobe to his doorway for a four-minute photoshoot, eight years after returning to Italy from a 13-year imprisonment in a US psychiatric hospital. It is a shame that one of the portraits is not represented here.

‘I captured his pain of living,’ Carmi realised. Umberto Eco was on the jury of a prestigious photography prize, awarded to Carmi for the Pound photos. He declared: ‘The images of Pound shot by Lisetta say more than anything that has ever been written about him, his complexity and extraordinary nature.’

Ten years later Carmi gave up photography and lived the last 46 years of her life in Cisternino, spreading the teachings of her spiritual guide, Babaji Herakhan Baba.

For more information you can visit the exhibition website by following this link.